With more than 6300 CAPS-equipped Cirrus aircraft out there and given all the unblinking security cameras running 24/7, it was inevitable that good video of a Cirrus parachute touchdown would eventually emerge. Earlier this month,it did. (More here.)

On March 5, an SR22 en route from Groton, Connecticut, to Republic Airport on Long Island suffered an engine failure near the airport. The pilot fired the CAPS and a camera caught the touchdown with unusual clarity. It’s not the first time this has happened, but I think it’s the one that offers the most compelling detail of what forces are involved at impact. According to the Cirrus Owners and Pilots Association, which keeps track of these things, the Long Island incident was the 77th CAPS deployment. Of these, 63 are what Cirrus and COPA like to call “saves,” but as an independent observer, I prefer to dispense with that label because it suggests no other outcome other than certain death was possible. That implication doesn’t pass the reasonable person test, in my view. But it’s nice marketing copy.

Two things occurred to me when I watched that Long Island footage for five or six times. First, sometime around 2000 or 2001, I stood in the Cirrus factory at the spot where the company had done some initial drop tests to gather basic load data on CAPS touchdowns. I recall being told—and I wrote as much—that the forces involved would likely injure the occupants and that there was no way the airplane would be repairable. Interestingly, although there have been many injuries and airplanes have been totaled, the outcomes have actually been better than Cirrus may have originally predicted. I think they were wise not to oversell the results.

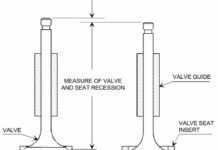

The general pattern has been only minor injuries and 14 of the airframes have been returned to service after the accident. Two of these must have been cursed, for they were repaired and later involved in a second accident, one of which was fatal. The Long Island airplane, as far as I know, wasn’t repairable, however. I saw a photo of the fuselage hacked in half and placed on a trailer or flatbed as only guys who recover totaled vehicles can do. During the impact sequence, you can see structure breaking off the lower wing—probably the flaps—and the thing takes an impressive bounce. Post-accident inspection of the engine revealed valve impressions on all of the piston tops, according to the NTSB’s preliminary. Huh? Did the cam go on strike?

So let’s run the score. Of 77 total events, 22 or 28 percent involved injuries of some kind. That count is for accidents with at least one injury, not individual injuries, whether minor or serious. The pilot of the Long Island airplane had a scratch on his head, but it was still listed as a minor injury. Nine of the CAPS events—or 12 percent—involved fatalities. That means that in 64 percent of the accidents, none of the occupants were injured. I don’t recall Cirrus putting a number on outcomes, but I got the impression they didn’t think it would be that high. I wouldn’t call it perfect, by any means, but it’s far better than the alternative.

Interestingly, the pilot himself and a couple of the quoted first responders said the accident outcome was a lucky, chance thing. But not really. If the airplane had landed on the roof of the building, the outcome would have been little different, other than someone probably needing some roof repairs. If it had grazed the edge of the building, same deal. A wilder ride, but I’d bet no different outcome. The real nightmare would be descending into power lines.

To be fair and to show how numbers can be made to show anything you want them to show, if accidents involving CAPS deployed outside of its operating envelope are culled, the fatals drop to just one or two, depending how you wish to interpret what happened. Several were clearly outside the system’s speed or altitude envelope and at least two probably were. One was a midair involving fire. Two points: It’s fair to include these out-of-envelope deployments because homo the sap is a necessary part of the CAPS idea. Call it total system evaluation. On the other hand, if the system is deployed within its operating envelope, it works at least as well as advertised and, if you consider Cirrus’ early claims, perhaps a little better.

The lucky juxtaposition of that security camera had an interesting effect. A couple of the local stations ran with the footage and added other footage, such as the Coast Guard’s excellent footage of a CAPS ditching in the Pacific in January 2015, to make pretty decent, in-depth stories on the entire concept of whole-plane parachutes. Even though these have been out there for nearly 20 years, it seems broadcast reporters discover them anew every few months, producing an interesting gee-whiz story. That’s actually a good thing.

Where I’m going with this, other than to show the illustrative video, is to compare the CAPS idea to the next big thing: autopilot autonomy to pull an aircraft out of extremis and landing it automatically. I’ll look at that in the next blog.