GPS Jamming Tests Frustrate Pilots, Controllers

Just as civil aviation has become thoroughly addicted to GPS, the military is trying to wean itself off that dependence and that’s causing some fractious conflicts in the Southwest. The…

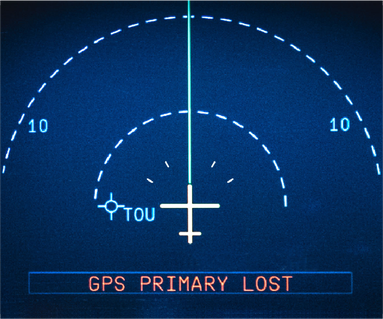

Just as civil aviation has become thoroughly addicted to GPS, the military is trying to wean itself off that dependence and that’s causing some fractious conflicts in the Southwest. The military uses the wide-open spaces to purposely jam GPS signals to see how its equipment and personnel cope with the “GPS denial.” But according to IEEE Spectrum, the military and the FAA are not always on the same frequency when it comes to managing those tests and controllers and pilots have put their frustrations in writing in NASA’s Aviation Safety Reporting System. "Aircraft are greatly affected by the GPS jamming and it's not taken seriously by management," says one report gleaned by IEEE Spectrum. "We've been told we can't ask to stop jamming, and to just put everyone on headings.”

The military does notify the FAA about jamming activity but that doesn’t always seem to get to the frontline workers in the system and the loss of GPS can be dangerous. One of the reports involved a business jet that made a wrong turn and ended up in the highly restricted airspace of the White Sands Missile Range, which, ironically, is the source of much of the jamming. Another pilot reported he lost his terrain mapping at a critical time and worried he’d end up in a smoking hole. When the jamming starts jamming up the system, controllers have the option to request a “stop buzzer” to get the military to turn off the electronic interference but some controllers complain they’ve been told not to make those requests and to just issue vectors to affected traffic. The FAA told IEEE Spectrum that controllers can, indeed, stop the tests if they think it’s necessary but those requests are automatically reviewed by upper management.