Accident Probe: VFR Into IMC, Part n+1

We’ve long maintained that weather poses the greatest risk on any given day to a proficient pilot flying a well-maintained aircraft. Presuming there’s adequate fuel aboard and the pilot knows…

We’ve long maintained that weather poses the greatest risk on any given day to a proficient pilot flying a well-maintained aircraft. Presuming there’s adequate fuel aboard and the pilot knows how to ensure that it gets to the engine(s), it’s more likely than not that the flight will be completed pretty much as planned. Everything falls apart, however, when we fail to consider and/or appreciate how poor weather conditions—including low clouds and visibility, or the turbulence associated with convective activity—can and will disrupt our plans.

These days, it’s child’s play to have multiple displays filled with information telling us not to be in a certain area. But without a sober assessment of the conditions relative to our situation and capabilities, the adverse weather we encounter is likely to win any contest of wills every time. It’s especially disappointing that pilots of airplanes equipped with the latest technology regularly seem to put their faith in the equipment they carry rather than a realistic assessment of their training, skill and competence. And we would argue that a pilot lacking an instrument rating is at a severe disadvantage when considering cross-country flights during which a variety of weather can be encountered. This month’s Accident Probe provides yet another example of what can and will happen if we let it.

Background

On March 31, 2019, at about 1439 Mountain time, a Cirrus SR-22 was destroyed when it struck terrain after its pilot reportedly lost control in instrument conditions near Farmington, New Mexico. The solo non-instrument-rated private pilot (male, 59) was fatally injured. While the nearest observing station reported visual conditions with gusty winds, instrument conditions associated with a line of rain showers existed nearby. The flight departed Halls Crossing, Utah, at about 1345 with Big Spring, Texas, as its destination, a familiar route for the pilot.

By 1409, the airplane was cruising at 17,300 feet MSL and receiving VFR flight following services from ATC. At 1428, the airplane entered a descent to 9300 feet and was given a frequency change. No other radio transmissions were received from the pilot. By 1438:10, the airplane had descended to 8575 feet MSL (about 3000 feet AGL). It then entered a tight, descending right turn at high speed. The last recorded data point, with the airplane southbound at 6850 feet MSL, works out to an average descent rate of about 5175 fpm.

Investigation

The accident site was located at about 1700. The debris field was 450 feet long, oriented on a heading of about 210 degrees. The airframe parachute was not activated. Although the engine sustained significant impact damage, there was no evidence of catastrophic failure. The spark plugs’ appearance was normal, and both turbochargers showed signs of rotation at impact. A crash-hardened data module installed in the vertical stabilizer did not record the accident flight.

Earlier on the day of the accident, the National Weather Service issued a convective outlook forecasting areas of general thunderstorms for the accident site location and time. A convective SIGMET was valid, as were AIRMETs Sierra (mountain obscuration and/or IFR) and Zulu (ice).

According to the NTSB, “Analysis of weather information indicated that the airplane likely encountered a line of developing and expanding rain showers, with updraft and downdraft conditions, precipitation, and reduced visibility as the pilot likely descended to fly under the cloud bases. Due to the developing and expanding rain shower line, outflow boundaries and low-level wind shear conditions were likely present in the area at the accident time.”

The pilot’s flight logbooks were not recovered. Two years earlier, the pilot reported 270 hours total time on his medical certificate application, with 64 hours in the previous six months. Also in 2017, the pilot attended a Cirrus transition course that included classroom and in-flight training. Fueling records indicated the pilot added 65.2 gallons of fuel on March 29. There was no evidence the airplane flew between then and the accident flight.

The airplane was equipped with an ADS-B In and Out transponder, plus an Avidyne multifunction display capable of displaying satellite-based weather information. Damage to the unit precluded a confirmation that it was receiving either type of data. The pilot also was using an iPad configured with the ForeFlight EFB application. When the application accesses the internet to retrieve weather data, a record of the transaction is logged at a ForeFlight facility. As the iPad was significantly damaged, there’s no record of any weather data delivered to it via ADS-B In or satellite.

Archived ForeFlight data indicate the pilot used the app to view weather imagery on ForeFlight on March 27, and to retrieve weather information and file a VFR flight plan on March 29, with a planned departure of 1500 on March 31. The data provided was not valid beyond 1200 on March 31. There was no record of the pilot receiving or retrieving any additional weather information.

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “The non-instrument-rated pilot’s continued visual flight rules flight into an area of forecast instrument meteorological conditions, which resulted in spatial disorientation and a subsequent loss of control.”

The NTSB added, “The reduced visibility and the pilot’s lack of experience in flight by reference to instruments provided conditions conducive to the development of spatial disorientation, and the airplane’s descending turn, rapid descent, and high-speed impact with the ground were consistent with the known effects of spatial disorientation.”

The NTSB added, “When activating his flight plan, the pilot indicated to the weather briefer that he was aware of the AIRMETs; however, whether he was aware of the SIGMET was not determined based on the available information.”

We’ve said something like this before, and we keep having to say it again: If you’re using an airplane for personal transportation, there’s no substitute for the instrument rating. It’s the single most important bit of training one can obtain for operating a general aviation airplane.

Beware The NEXRAD Lag

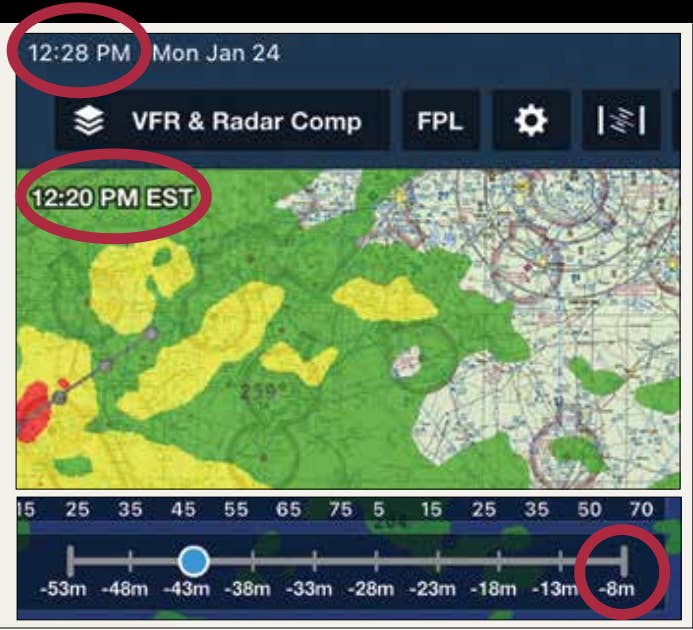

There are a number of latency issues with the NEXRAD weather information that’s been widely available in general aviation cockpits since the early 2000s. In 2012, the NTSB summed them up in Safety Alert SA-017, “Actual Age of NEXRAD Data Can Differ Significantly From Age Indicated on Display.” Among the challenges identified by the NTSB are:

- The cockpit display’s age indicator references the age of the mosaic image created by the service provider, not the age of the actual weather conditions as detected by NEXRAD. The mosaic image will always be older than the age indicated on the display.

- In extreme scenarios, the actual age of the oldest NEXRAD data in the mosaic can exceed the age indication in the cockpit by 15 to 20 minutes.

Aircraft Profile: Cirrus Design SR22 GTS G3

OEM Engine: Continental IO-550-N

Empty Weight: 2250 lbs.

Maximum Gross Takeoff Weight: 3400 lbs.

Typical Cruise Speed: 180 KTAS

Standard Fuel Capacity: 92 gal.

Service Ceiling: 17,500 feet

Range: 1000+ nm

VS0: 59 KCAS

This article originally appeared in the March 2022 issue of Aviation Safety magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to Aviation Safety!