Putting A Face To The Perils Of Space Flight

It’s easy to take all the SpaceX rocket explosions lightly until someone you know is likely to be a passenger on one.

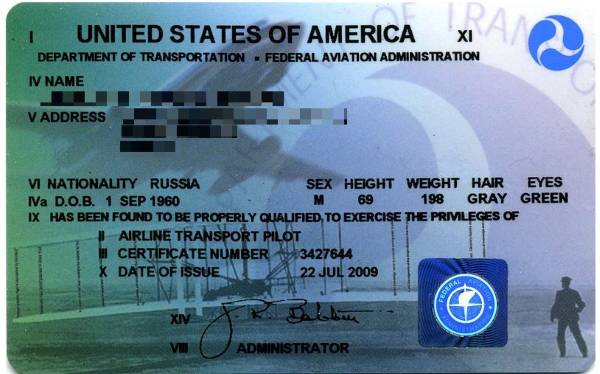

Government of Canada Photo

As you can imagine, we get a lot of email here at AVweb and it's frankly overwhelming. Over the years I've learned to discern the potentially fruitful communications in terms of newsworthiness, and I open and read them carefully. The rest, I'm afraid, run the risk of remaining unopened on our server and for that I apologize. We have room for a very limited amount of news and have only so much time to research and write stories.

Having said that, we are willing to be prodded into action. If you have something you think should really, really be shared with our readers, try again and convey some urgency. Chances are someone will have a look.

I offer that as context for the purely random chance that I came across SpaceX for the first time. The subject line said something benign like "interesting" or "look at this" which can trigger a click from me and in this case it did. I was so blown away by what I saw on the attached video that I immediately put it at the top of our page.

In a scene right out of Buck Rogers, a small rocket was shown maneuvering around an untidy plot of land littered with bits and pieces of other rockets. It moved seemingly randomly, always remaining perfectly vertical about 100 feet off the ground but changing altitude, too.

It finally settled on a small concrete pad and remained upright. That means it was a rocket with full directional and throttle control at a time when every other rocket booster was essentially a container for a controlled explosion that, once lit, burned at full power until it either ran out of fuel or the fuel was cut off, which was the limit of control.

Fifteen or so years later we don't even think twice about SpaceX recovering boosters by landing them on drone barges bobbing in the ocean or back at the launch site. The company has virtually taken over the commercial launch business and so far has a perfect safety record.

It didn't start that way. During the development of the myriad technologies involved in that magic, SpaceX lost many vehicles, often in spectacular fashion. It was, as we've all more or less come to accept, a trial-and-error method of flight testing that channeled resources into progressive real-time data collection on actual failures instead of trying to prevent those failures in pursuit of the flawless first launch.

Massive explosions are kind of anathema to the FAA and its resistance to SpaceX's seemingly cavalier attitude toward the safety that is the agency's core responsibility became a hot topic and probably delayed development. SpaceX founder Elon Musk bears some responsibility there. I haven't decided if he's irritatingly smug or smugly irritating but he has definitely chafed his way to the top.

I was among the chorus urging the FAA to let SpaceX keep blowing things up as long as they made progress without hurting anyone. The FAA has at least partly come around on that. Witness the relatively quick progression of testing on Musk's crowning achievement, his Starship system, and the equally spectacular results so far. All three test flights ended in massive explosions, but test two's rapid unplanned disassembly happened much later in the flight than the first and the third actually almost completed the mission.

But rather than join the cheer squad of optimists hyping the "progress" of the test program, I have growing discomfort in the pit of my stomach. You see, I kind of know one of the astronauts who will likely fly on the system at some point in the future.

Col. Jeremy Hansen will be one of four crew members on the second NASA Artemis flight, a lap around the moon as a precursor to mankind's return to the moon on Artemis 3. Hansen's mission will be launched by the NASA Space Launch System, which is basically the same as the system used to launch the Space Shuttle. It's as proven as any launch system can be, I suppose, but there are certainly no guarantees in space flight. He and his crewmates will be the first to occupy Lockheed Martin's Orion crew capsule, which did a dress rehearsal for the moon flight in 2022 without anyone onboard.

Anyhow, it's almost certain that Hansen will return to space on the Starship system at some point in the future, maybe even on a trip to Mars, which is the ultimate goal of the system. But even though I would never presume to call him a friend, I have to admit our chance acquaintance has given me a different perspective on the risks and rewards of space exploration.

Hansen was in the exhibitor's space next to mine at an airshow in Hamilton, Ontario, about 10 years ago. I was hawking subscriptions and swag for another publication so Hansen definitely had the cooler gig. He had flown an F-86 Sabre owned by Vintage Wings of Canada, a private collection in Gatineau, Quebec, to the show. An F-18 pilot with the Royal Canadian Air Force, Hansen had recently been named a Canadian Space Agency astronaut, but this was the weekend and he was volunteering as the Sabre pilot.

Hansen spent the day talking to hundreds of people about the airplane, which was one of the star static display attractions, and his new job. He had his photo taken hundreds of times, answered at least as many questions, most of them over and over again, and kept a smile on his face the whole time. I sold a few subscriptions and ball caps.

He also agreed to write an article for a flight training guide for this other publication I was representing. We chatted about the experience he and my son, also an RCAF pilot, shared as teenaged members of the Royal Canadian Air Cadets and students at Royal Military College, both important pipelines for future military pilots and, yes, astronauts.

The show had an unusual configuration in that the spectator and exhibit area was on a grass infield on the other side of an active taxiway. Almost all spectators and exhibitors got to the infield on one of dozens of school buses that shuttled to the parking lot. As an exhibitor, I was allowed to park my rental car behind my booth.

After Hansen had buttoned up the Sabre and I had packed up my booth, I saw him kind of wandering around the beautiful Cold War fighter in indecision. He didn't have any way out of the infield except to join one of the hundreds-long lineups for a bus. I asked if he'd like a ride with me in the rental and he gratefully accepted.

It turned out he was going to meet his cousin at the terminal and spend the evening with family. It took about a half-hour for us to get back to the terminal and we talked about flying, the Air Force and his profound honor at being selected as an astronaut. It was my honor to spend quality time with such a quality individual.

Now it's not like we forged any kind of bond. He didn't even accept my friend request on Facebook and wouldn't know me to see me. But he certainly left a lasting impression on me. So the perils of space flight considered against a backdrop of exploding rockets come into a little sharper focus when you've sweated out an airshow in the southern Ontario humidity with one of the people who will travel on one of those rockets.

So, I hope history repeats itself. I hope the explosions stop and fade into a seemingly distant memory as the Starship system proves itself a capable and reliable way to chip away at mankind's insatiable need to explore and learn about the cosmos.

And I wish Godspeed to Col. Hansen and all the other profoundly talented and incredibly brave people who are scratching that itch for the rest of us. And thanks for a pleasant afternoon.