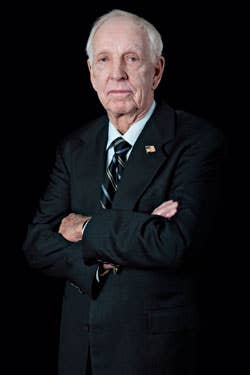

Remembering Al Haynes

The weight of command is sometimes no heavier than four shoulder stripes. Captain Haynes prevailed when the burden was far greater.

I have never been to Skaneateles, New York. I do not now plan to go to Skaneateles, although the brochures look nice. It has an airport and I know this because throughout the 1990s, at least once a month, I placed a revised approach plate for the Skaneateles VOR-A approach in my Jeppesen binder on the off chance that I might divert there some cold and icy night.

That previous sentence will evoke memories for some pilots, perhaps pleasant ones of handling those rich leather binders or maybe a grateful sigh for no longer suffering the tedium of inserting approaches into a book you’d never open to prepare for a trip you’d never make. More likely, many will wonder … what leather binders?

This blog is not about the binders but who got the stuff in the binders to the people stuffing them. Captain Al Haynes did that as a minor part of his job as a United skipper on the DC-10. You’ll recall that Haynes died this week in Seattle after a brief illness. He was 87.

My friend Todd Huvard texted me a photo of a wrinkled and muddy Jeppesen revision envelope he had received in the mail with a single-sentence letter from the Sioux City, Iowa, postmaster. “The attached mailing was recovered from the United Airlines Flight #232 which crashed and burned in Sioux City, Iowa on July 19, 1989.”

He wasn’t the only one who got that letter. A lot of pilots did that summer because UA 232 had originated in Denver where Jeppesen was and is headquartered and where it threw a lot of mailbags on airliners. An instrument student of mine got one, too. And I won’t be surprised if someone reports in the comments a similar surprise in the mailbox. If so, I bet you still have it.

If you think a little about it, it shows a level of dedication and duty of care that people went out in that muddy cornfield and collected mail and who knows what else that had been scattered over acres after a horrifically violent touchdown. And then bothered to commemorate it with a letter. It’s also a fine testament to Haynes himself, for he had a similar attitude to his passengers and crew.

I met and interviewed Haynes sometime in 1996 or 1997, I think. We had invited him to speak during International Aviation Week in the Cayman Islands, which I helped organize. Captain Haynes had a quality I can best describe as spiritual, not in the religious sense, but in the human sense.

What I vividly recall about his talk on UA 232 is the thoughtful, tender way he described his concern for the people aboard that stricken DC-10. I can’t recall the words exactly now, but he conveyed to a rapt audience the enormous responsibility the pilot in command of an airliner must shoulder and how that burden can approach the unbearable when dull routine turns to a nightmare that even the most sadistic sim operator could never imagine.

He did not tear up, either during the interview or his presentation. But I was made to understand—and I suspect the audience did, too—what it might be like to stare into the black maw of survivor’s guilt, of knowing that 185 souls were saved, but 111 were not. He explained in lucid detail what it was like in that cockpit, but landing the airplane may have been the easy part compared to what followed. He did this with such grace and dignity, that it’s tempting to say that he and those of his generation were of a unique breed.

I doubt he would say that. Nor would I, for I’m certain there’s a 28-year-old regional pilot out there somewhere who could rise to a similar occasion, if asked. If I ever meet him or her, I can only hope the circumstances are less tragic.