The Yeager Legacy

Chuck Yeager stood astride the leather helmet flight test era and the emergence of space flight. He was perfectly positioned to usher in the new era.

There were four men in the cockpit of the B-29 that day and as a famous writer would later observe, no one knew their names. They soon would. It was July 4, 1947, and the B-29, piloted by Bob Cardenas, was flying west to the high desert from Buffalo, New York, with the Bell XS-1 slung under the open bomb bay. Flying with him was the impossibly small (and young) team that would, in just three months, write history by propelling the X-1 beyond Mach 1. Bob Hoover was chase, Jack Ridley was the project engineer and Chuck Yeager, the pilot. He was just 24.

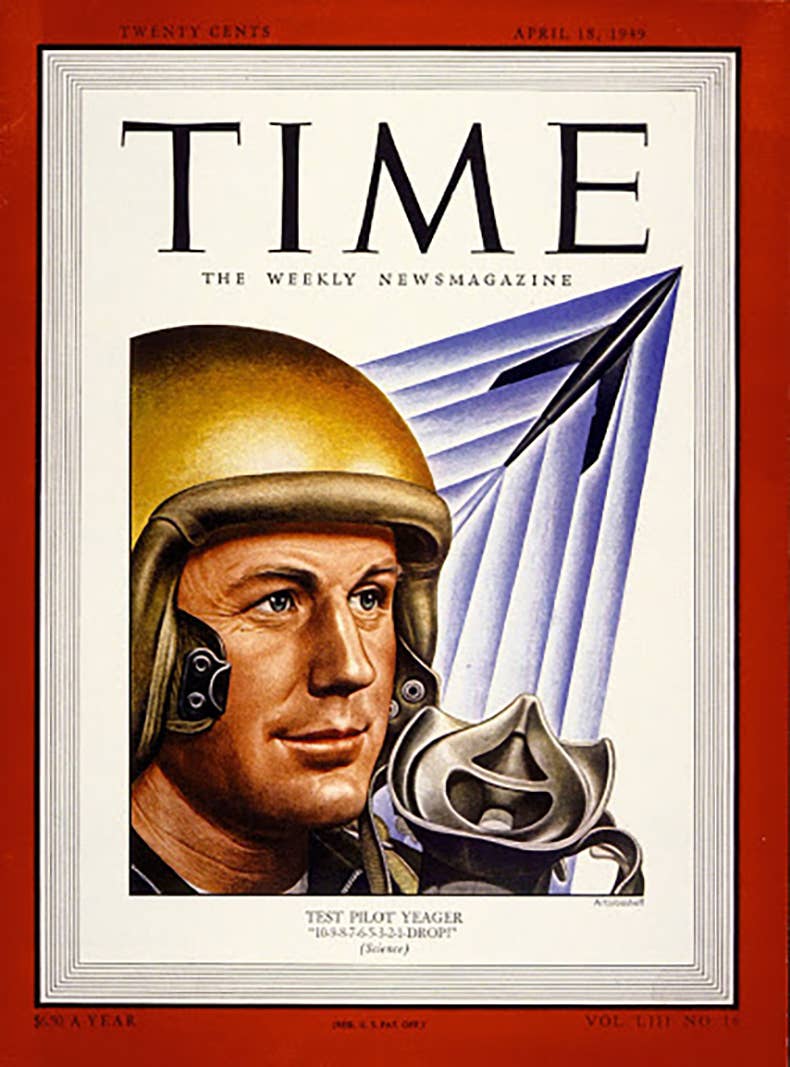

With Yeager’s passing this week at the age of 97, only one man remains, Bob Cardenas, who just celebrated his 100th birthday in a profession not necessarily known for longevity. All four are known in the aviation world or certainly in the flight test community. But only Yeager ascended into that rarefied strata that put him on the cover of Time magazine in 1949, a year and a half after the fact.

From the sidelines with time and words to spare, writers, bystanders and the star-struck can speculate on why Yeager, a low time-in-grade Air Force captain among many of the same, rose to become the very definition of stick-and-rudder prowess under duress. Even Yeager himself said other pilots of his era—especially Hoover—had equivalent skills and similar experience. A reading of various sources quoting Yeager suggest a realistic dose of right time, right place.

In his first biography, "Across the High Frontier," Yeager had no ready explanation of why Colonel Albert Boyd, then head of the test and evaluation command at Wright-Patterson field, culled him from a herd of highly competent pilots, some of whom had more flight test time and project experience. Perhaps Boyd was, as Yeager speculated, impressed by the young captain’s mechanical ability or, as Yeager critics sometimes claimed, saw him as young and expendable. Boyd would later say he picked Yeager because he was “rock solid” and reliable.

What really mattered is what transpired during the X-1 test program and how quickly it moved. Just 101 days after arriving at Muroc, Yeager was famously photographed standing brashly atop the X-1’s thin wing as it was towed in after the Mach 1.05 flight on Oct. 14, 1947. The Air Force hushed the actual event, but by the time Yeager shook hands for the camera for the 1947 Collier Trophy—awarded a year later—he was no longer an obscure O-3 in the test command.

And there the pivot.

Yeager’s own words explain his canonization in the oddly awkward second-person prose William Lundgren used in "Across the High Frontier": “They give you a medal here and trophy there. But you don’t fool yourself. You were losing out. In peacetime, military pilots have always been looked down on, especially Air Force pilots in Flight Test. You were nothing a few years back, but old diehards who couldn’t get by on the outside.”

“But this project opened a few closed eyes. It gave Air Force test pilots a prestige they’d never had before. All men who fly respect you now for what you’ve done together, for what they know you’ll go on to do. That, in addition to its assigned objective, is what this project accomplished.”

And Yeager did go on. Boyd had warned him that the Mach 1 flight would be as momentous as the Wrights’ at Kitty Hawk and the glare would be blistering. Perhaps that’s what Boyd saw when he described Yeager as “rock solid,” someone who could maintain his bearings under unyielding publicity. It’s possible that Yeager was uniquely qualified to carry the torch, for he did the appearances, gave the speeches and signed the autographs and described it all in a word that has lost some of its luster today: duty. He carried on with this long after he left the Air Force in 1975 as hundreds of EAA attendees can attest. He gave generously of his time for the Young Eagles program.

Boyd may have had his doubts, however. In one test report on an X-1 flight, Yeager was supposed to do a fly-by for dignitaries convened at Muroc but decided instead to point the airplane straight up with all four chambers roaring to disappear into the stratosphere over the high desert. He had no explanation other than impulse. Dick Frost, Bell’s chase pilot assigned to the project, may have been similarly disposed when he was startled to see Yeager roll the X-1 under power immediately after the drop on the Mach flight.

All of this, of course, is part of the Yeager legend but also the Yeager legacy. When he was named the first commandant of the USAF Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in 1962—a year after the first Soviet and U.S. space flights— Yeager was perfectly positioned to be an emissary from the leather helmet days of flight test to the emerging space age. Yeager stood astride both and ushered in the era of the highly educated, specialized flight test pilot just as conversant in science and engineering as in flying. The guy who went off the test card to roll a rocket plane was instrumental in building a new culture teaching pilots not to do that very thing. (I wonder if any still do.)

No less than Jimmy Doolittle summed up Yeager’s career even while it was in midstream: “In his own modest perspective, he was simply a test pilot who had a job to do. In the light of aeronautical achievement, however, he is one of the dedicated air pioneers who have repeatedly risked their lives to extend man’s knowledge and the horizons of flight.”