Will Boeing Tariffs Ignite A Trade War?

No one knows. But if approved, the tariffs will directly impact U.S. workers.

The great test to unravel the globalized nature of modern economies was going to happen sooner or later. The just-announced U.S. tariff against Bombardier's CSeries airliner may not be the first shot nor even the biggest, but it's illustrative of how difficult placing U.S. trade interests above all else will be. The modern aerospace industry is thoroughly globalized for the simple reason that airplane builders have found efficiencies in outsourcing components to the most efficient producers. The CSeries is a case study in this.

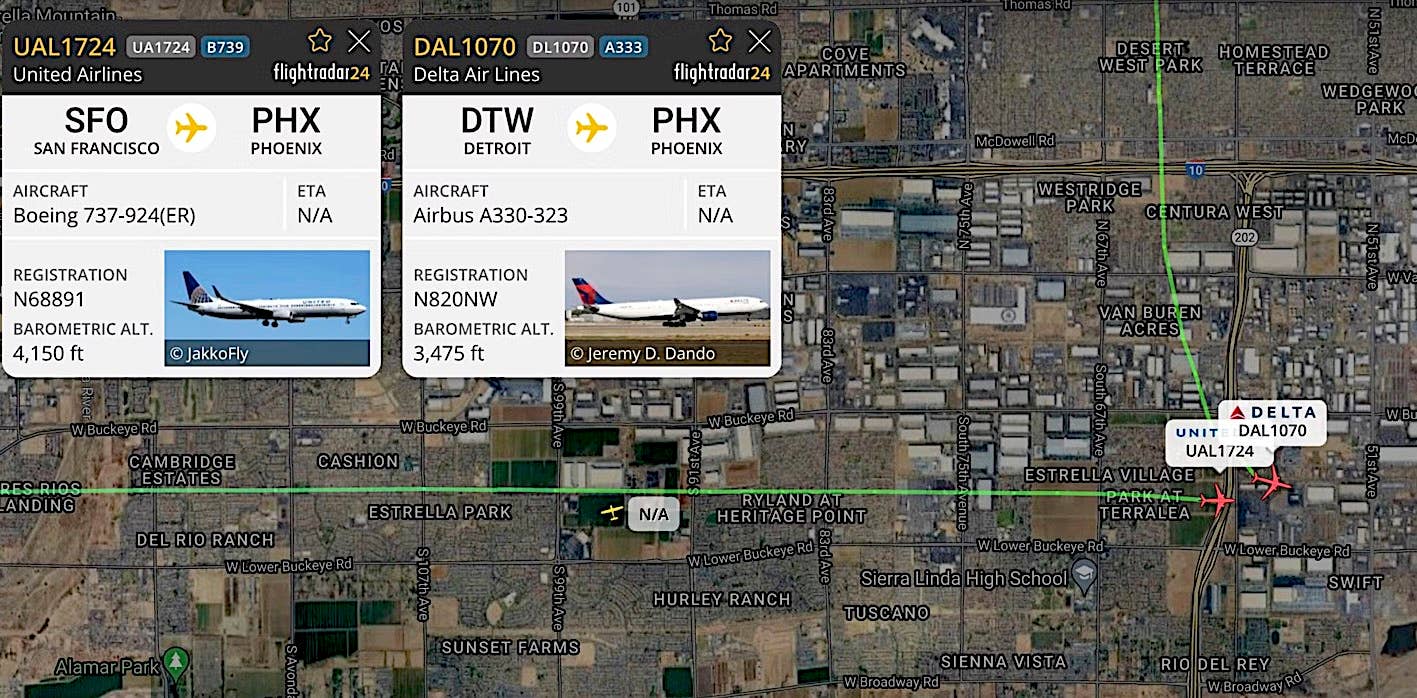

Boeing's beef with Bombardier is that it's dumping the CSeries into the U.S. market with a giant 75 airplane order from Delta worth $5.6 billion. Boeing argues that because Bombardier got a $1 billion bailout from the Quebec government, the Canadian company has an unfair competitive advantage.

Boeing claims that Delta is getting the CSeries jets for $19.6 million, less than half the cost of a Gulfstream G600 and two thirds of the $33 million Boeing says it costs Bombardier to build the things. Absurd, replies Bombardier. Boeing proposes a tariff of 219.63 percent to level the field. If it's approved, that would raise Delta's price on the CSeries to about $40 million each or about $10 million less than the price of Boeing's 737 NG. Those two airplanes aren't exactly direct competitors, at least at the low end of the passenger capacity scale, according to Delta. The CS100 can have as few as 100 seats, while the 737 NG is more like 130. When Delta approached Boeing for something smaller, it said Boeing had no American-made product to offer because it ended the 717 more than a decade ago. Delta said Boeing offered it a batch of used Embraer E190 regional jets it took in on trade-in. (If this sounds like the car business, it's not that different.)

The proposed tariff has to be reviewed by the U.S. International Trade Commission, which is supposed to be a bipartisan, quasi-judicial panel that adjudicates trade issues. While the notion of "bipartisan" seems a quaint concept of the last century, the USITC nonetheless has to explain why it thinks the tariff is warranted. Presumably, it will have to do so with actual data so perhaps we'll see enough information to judge the merit of Boeing's claim.

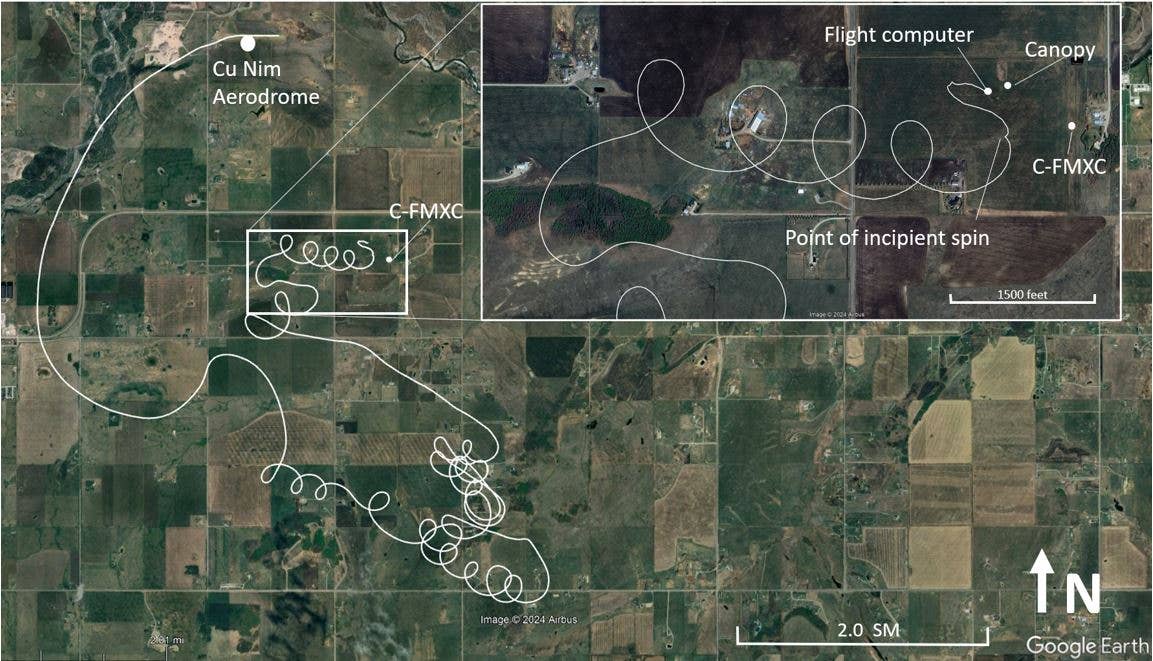

If the commission approves the tariff and it tanks the Delta purchase, then what? Is Boeing the winner? I'm not sure I see how, since Boeing doesn't have an airplane that Delta considers competitive. If a tariff kills the CSeries program or even the company itself—probably a stretch—there will be implications beyond Boeing. More than 50 percent of the CSeries components are U.S. sourced, including the Pratt & Whitney geared turbofans that are central to the CSeries' exceptional efficiency. Moreover, the tariff announcement got the attention of our allies across the Atlantic. The CSeries wings are manufactured in Northern Ireland and a host of other components are built in other parts of the world. Boeing has also been reminded that it has a $5 billion order pending from Canada for F/A-18 aircraft. The politics get even more complicated if the U.S. expects Canada to participate in its overseas adventures using such aircraft.

Depending on the USITC's ruling, it's not unthinkable that the Boeing deal could spark a more vigorous trade war across of a range of imports and exports. The politics of this are unpredictable. No one can tell if America-first rhetoric is just a fashionably thin veneer of political blabbering or a deeply held sentiment that's about to crash head on into the reality of global economics. Historically, trade wars have been circular firing squads and there's no reason to believe that's any different today than it was a century ago.

I've reported previously that companies like Lycoming and Continental are reducing their outsourcing and bringing some manufacturing back in-house. There's also a discernible trend of so-called re-shoring of manufacturing in the U.S., but it's by no means a torrent. Companies outsource for many reasons, but one is that they find efficiencies in engaging other companies who can produce components and subassemblies at lower cost. In aerospace, outsourcing has been a means of reducing the staggering investment required to produce a product like a new airliner. If the political winds shame companies into re-shoring when they otherwise would not, all that will do is make them less competitive, a dangerous direction to go with China looming as an aerospace competitor. Why wouldn't the same calculus apply to Canada?