Accident Probe: Not Bulletproof

Even before I started taking flying lessons, I was exposed to aviation. Without a formal frame of reference, I absorbed what little I could from other pilots’ stories, reading about…

Even before I started taking flying lessons, I was exposed to aviation. Without a formal frame of reference, I absorbed what little I could from other pilots’ stories, reading about flying in books and magazines like this one and, tragically, learning how some of them came to grief. That usually involved poor weather. It took a while, but I was determined to get my private certificate, and then the instrument rating. Both were licenses to learn and, like so many others, I occasionally got in a little bit over my head during my “education.”

One of the earliest things I learned about flying was that poor weather and personal airplanes don’t always get along. Of course, there’s weather no airplane should fly in, but locating the dividing line often wasn’t easy. It still isn’t, but I long ago learned to err on the side of caution, even if it meant delaying or outright canceling a long-planned trip.

I’m old-school in many ways, having amassed quite a few hours in the days when moving maps, electronic charts, in-cockpit traffic displays and long-range navigation mostly were science fiction, at least for personal airplanes. So I’m constantly amazed at the gadgets we have available today. I’m even more amazed that recently minted pilots place a great deal of reliance on their automation and not enough on skills or managing risk. Mainly though, I’ll forever be perplexed that VFR-only pilots still think they can rely on their autopilot instead of an instrument rating, and that they’ll launch into conditions that would have a rated pilot thinking twice. Here’s a recent example.

Background

On September 4, 2020, at about 2055 Central time, a Cirrus SR22 was destroyed when it collided with terrain near Chester, Ark. The non-instrument-rated private pilot (male, 31) and three passengers sustained fatal injuries.

After working his job the day of the accident, the pilot intended to fly with three passengers to South Carolina that evening. At about 1900, the pilot called his CFI/mechanic, apprising him of the plan. The CFI/mechanic advised the pilot to leave in the morning. At about 1949, the airplane was fueled with 36.41 gallons of 100LL avgas. The airplane departed Muskogee, Okla., about 2027 and proceeded east.

At about 2049, while climbing through 8500 feet MSL, the pilot obtained VFR flight-following services from ATC. The controller subsequently suggested a deviation for moderate-to-heavy precipitation. Shortly thereafter, the airplane turned into the area of precipitation, advising ATC he was returning to the departure airport. The airplane then flew northwest. When queried by ATC, the pilot said, “The wind caught me,” and that he was correcting. Instead, the airplane turned northeast and began descending. The controller then advised the pilot to turn left to 270 degrees. The pilot acknowledged the instruction, but the airplane continued to descend and turn right. Radar contact was lost at about 2055; the wreckage was found in wooded terrain the following day.

Investigation

The airplane impacted the terrain on a heading of about 220 degrees and at a 30-degree angle. The fuselage was fragmented. Flight control cable continuity could not be confirmed due to damage; however, the cable separations were consistent with overload.

The propeller was separated from the engine, and one propeller blade was separated just outboard of its hub. All blades displayed chordwise nicks and gouges; two of them exhibited S-bending. Observed spinner pieces exhibited spiral crushing.

The accident airplane was an early SR22, manufactured in 2001, which the pilot acquired in January 2020. The pilot received formal VFR transition training under the Cirrus Embark program, but did not complete portions of the online self-study. The training was not conducted at night or in IMC, and no extensive training on exiting inadvertent instrument conditions was conducted. The pilot also received simulated instrument training from his local instructor and was “good at it.” Recorded entries in the pilot’s logbook showed he did not meet recency of experience requirements to carry passengers at night. The NTSB estimated the pilot had accrued 162 total hours of flight time, with 37.8 hours in the SR22.

A developing stationary front was forecast to extend from Kansas southeastward through northeast Oklahoma and into Arkansas. The accident site was in its immediate vicinity. Satellite data showed an area of cumulonimbus clouds in the immediate vicinity of the accident site with tops near 38,000 feet MSL.

A pilot flying nearby about the time of the accident reported the storm had almost constant lightning. The pilot indicated “it was the most intense lightning in any storm that he had ever seen in his 25-year aviation career,” according to the NTSB.

A convective SIGMET was issued at 1955, including the area of the accident site, for a line of thunderstorms with tops to 42,000 feet with movement to the southeast at five knots. The sun set at 1939, and the moon had not risen at the time of the accident. The only record of a weather briefing was via ForeFlight, at 0026 that morning. There were no records of any requests for updates before the accident.

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “The non-instrument-rated pilot’s continued flight into dark night instrument meteorological conditions which resulted in spatial disorientation and a subsequent loss of airplane control.”

According to the NTSB, “The pilot’s inability to respond positively to ATC-provided vectors and maintain altitude before the turning descent is consistent with the pilot experiencing spatial disorientation. The pilot’s inability to maintain aircraft control under those conditions was likely exacerbated by the presence of frequent lightning.”

Even an early SR22 is a capable airplane, with a moving map and an autopilot. According to the NTSB, the pilot carried portable equipment to display NEXRAD weather radar and other in-flight data. But even a brand-new SR22 isn’t bulletproof. The low-time pilot’s CFI/mechanic gave him good advice—leave in the morning. Instead, he got in over his head, and lacked the experience to understand his education was incomplete.

Spatial Disorientation

The FAA’s Civil Aeromedical Institute defines spatial disorientation as a “loss of proper bearings; state of mental confusion as to position, location, or movement relative to the position of the earth.” According to the NTSB, contributing factors include “changes in acceleration, flight in IFR conditions, frequent transfer between visual flight rules and IFR conditions, and unperceived changes in aircraft attitude.

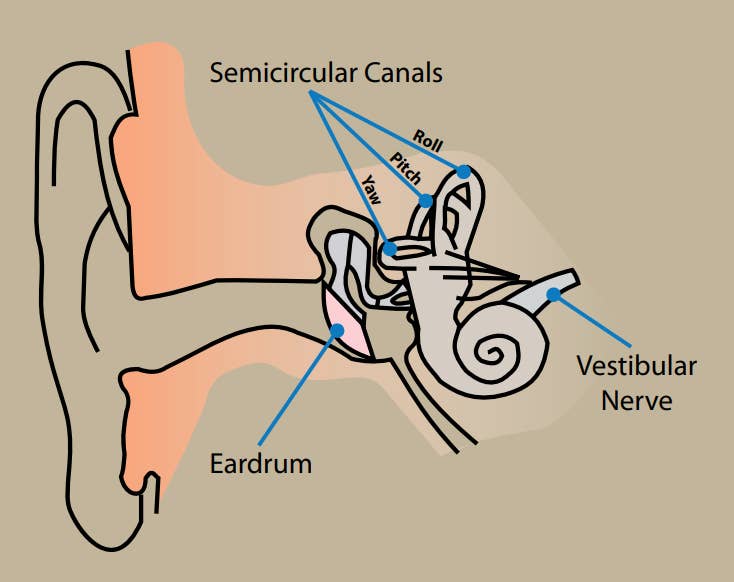

When in IMC, according to the FAA’s Airplane Flying Handbook (FAA-H-8083-3B), “The vestibular sense (motion sensing by the inner ear) in particular can and will confuse the pilot. Because of inertia, the sensory areas of the inner ear cannot detect slight changes in airplane attitude, nor can they accurately sense attitude changes that occur at a uniform rate over a period of time. On the other hand, false sensations are often generated, leading the pilot to believe the attitude of the airplane has changed when, in fact, it has not. These false sensations result in the pilot experiencing spatial disorientation.”

Aircraft Profile Cirrus SR22

OEM Engine: Continental IO-550-N

Empty Weight: 2250 lbs.

Maximum Gross Takeoff Weight: 3400 lbs.

Typical Cruise Speed: 175 KTAS

Standard Fuel Capacity: 81 gallons

Service Ceiling: 17,500 feet

Range: 1049 NM

VS0: 59 KCAS

This article originally appeared in the September 2022 issue of Aviation Safety magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to Aviation Safety!