Accident Probe: Oshkosh Or Bust II

Editor’s note: For our July 2021 Accident Probe, Oshkosh Or Bust, we explored an accident involving a non-instrument-rated pilot who took off into dark night IMC and crashed into an…

Editor’s note: For our July 2021 Accident Probe, Oshkosh Or Bust, we explored an accident involving a non-instrument-rated pilot who took off into dark night IMC and crashed into an open field near the airport, killing himself and his passenger. This month’s accident is eerily similar, except both occupants were instrument-rated commercial pilots. The underlying reasons for both accidents differ somewhat, but they share a common goal: flying to Oshkosh, Wis., for the annual air show. Get-there-itis is a real thing.

The FAA’s Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (PHAK, FAA-H-8083-25B) discusses five hazardous attitudes pilots may harbor. It defines “attitude” as “a motivational pre-disposition to respond to people, situations, or events in a given manner.” A hazardous attitude, meanwhile, “can interfere with the ability to make sound decisions and exercise authority properly,” according to the PHAK. As we’ll see, this month’s accident has the “anti-authority” hazardous attitude interwoven throughout.

But it also has the “get-there-itis” mentality, wherein pilots ignore normal procedures and/or adverse conditions in an attempt to begin or complete a planned flight. We’re sure this is more common than the accident record reflects, thanks in part to some combination of luck and skill allowing completion of the mission without the need to make an NTSB report.

And there’s a fine line between skillfully negotiating the many challenges a flight may present and doing it irresponsibly, with possible tragic consequences. The accident record tells us that line is often crossed.

To me, the real trick in all this is a pilot’s ability to recognize when he or she is getting in over their head, and making decisions only with the mission in mind, instead of soberly considering the possible adverse outcomes. Here’s an example of the former.

Background

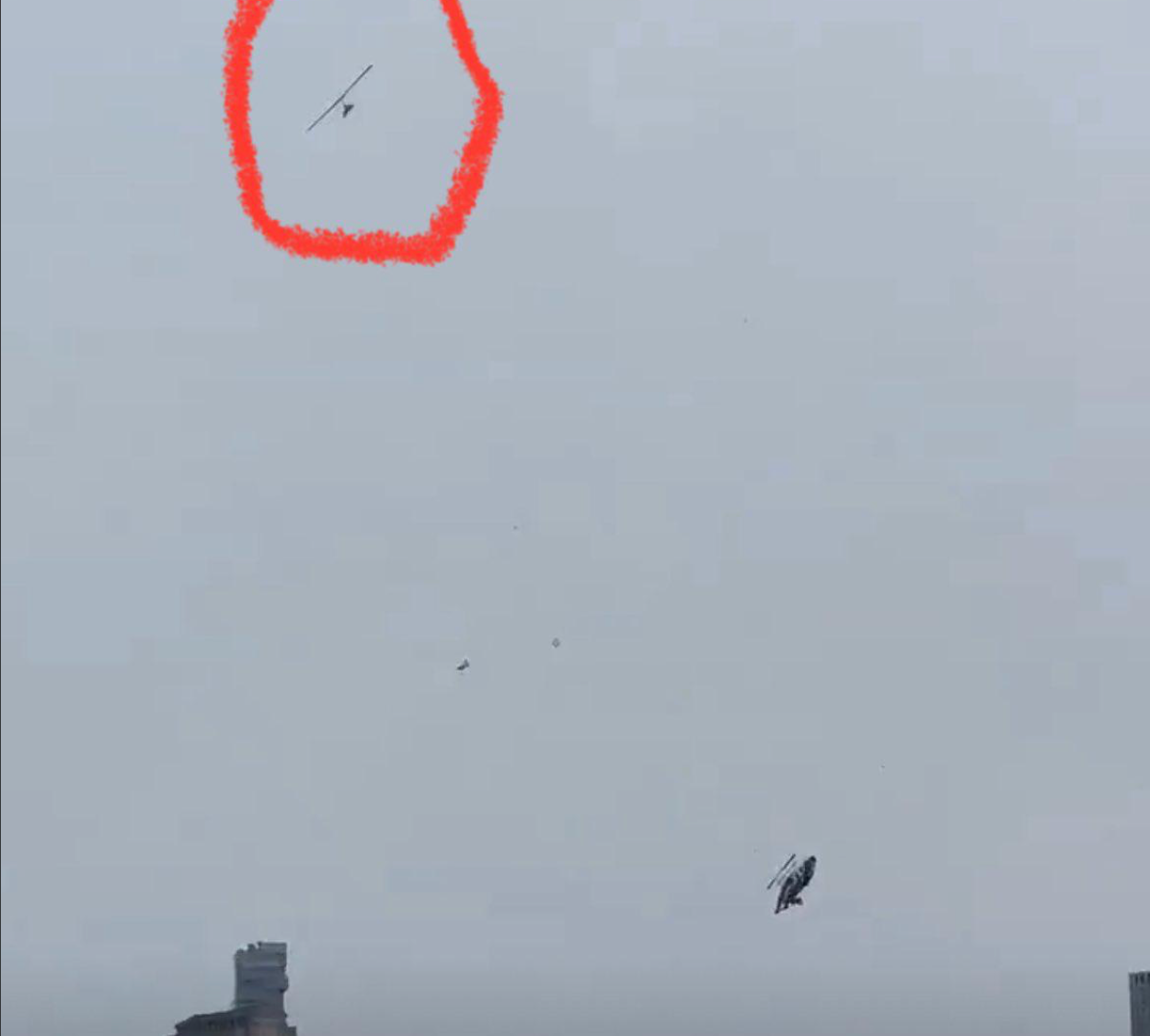

On July 24, 2019, at about 0550 Eastern time, a Cirrus SR22 was destroyed when it impacted terrain near Americus, Ga. The pilot and the pilot-rated passenger were fatally injured. Night instrument conditions prevailed; no flight plan had been filed. The pair was heading to Oshkosh, Wis., for the

annual air show.

Radar data consisted of six targets over a span of one minute, depicting a 180-degree arc to the left. The first target located the airplane about 1700 feet beyond the departure end of the runway at 900 feet MSL/432 feet AGL. The last target showed the airplane at about 1100 feet MSL.

A resident of the farm where the airplane crashed heard its engine at about 0550. He noted it was cloudy and still dark outside, and that the noise sounded like the airplane was turning and the engine was "whining really loud." Then he heard an explosion.

Investigation

The airplane came to rest at an elevation of 477 feet; all of its major components were accounted for at the scene. The wreckage path was about 400 feet long, oriented on a southerly heading. Initial contact was a tree strike about 34 feet above ground; a ground scar began about 50 feet beyond the tree strike.

The airframe and flight control surfaces were highly fragmented, including the rudder pedals and sidesticks, but control cable continuity was confirmed from the cockpit to associated bellcranks, and to their overload breaks and cuts by first responders. This was an early, non-glass SR22: its gyro instruments displayed rotational scoring, indicating they were operating at impact.

The oil filter was dated July 7, 2017. It was disassembled; no metallic debris was noted. The propeller had separated from the airplane; all three propeller blades remained attached to the hub. Each displayed similar twisting, bending and chordwise scratching, indications the engine was running at the time of impact. The Cirrus Aircraft Parachute System’s activation handle still had its safety pin attached, including its “Remove Before Flight” banner.

According to the airplane’s logbooks, the most recent annual inspection was completed April 3, 2018. The last three annual inspections were completed about every other year.

“There were no anomalies noted with the airplane that would have precluded normal operation,” the NTSB said.

The 0550 recorded weather observation at the departure airport, about two miles south of the accident site, included an overcast ceiling at 500 feet and wind right down the runway at five knots. Visibility was 10 miles. At 0445, an updated AIRMET Sierra was issued, advising of IMC with ceilings below 1000 feet and visibility less than three statute miles, with precipitation and mist. Weather satellite data indicated the approximate cloud-top height over the accident site was 6500 feet MSL. Civil twilight was to begin at 0619, with sunrise at 0646. There is no record of the flight’s pilots receiving a weather briefing through Leidos or ForeFlight. It’s not known if they obtained weather information from any other sources before the accident flight.

The pilot/owner (male, 69) held a commercial certificate and an instrument rating. (An early version of this NTSB report stated he had 22,000 total hours, something dropped from the final.) The pilot-rated passenger (male, 63) also held a commercial certificate with an instrument rating.

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “The pilot’s decision to depart in dark instrument meteorological conditions, which resulted in spatial disorientation and subsequent loss of airplane control. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s and pilot-rated passenger’s self-induced pressure to complete the flight and the pilot’s anti-authority attitude.”

Given the pilot/owner’s failure to obtain a weather briefing, file an IFR flight plan or regularly inspect his airplane, the NTSB says “it is likely that he had developed an anti-authority attitude, as evidenced by the disregard for several rules and regulations.” In addition, the NTSB noted, the pair may have experienced “get-there-itis” in attempt to get to the air show.

The sidebar below highlights some details about both the anti-authority hazardous attitude and “get-there-itis.” Acknowledging you may be experiencing one or both, or other emotional distractions, is the real key to avoiding the bad decisions that result.

‘Effective Risk Management Takes Practice’

According to the NTSB, “By identifying personal attitudes that are hazardous to safe flying, applying behavior modification techniques, recognizing and coping with stress, and effectively using all resources, pilots can substantially improve the safety of each flight. Remember that effective risk management takes practice. It is a decision-making process by which pilots can systematically identify hazards, assess the degree of risk, and determine the best course of action. Pilots should plan ahead with flight diversion or cancellation alternatives and not be afraid to change their plans; it can sometimes be the difference between arriving safely late or not arriving at all.”

Aircraft Profile: Cirrus SR22

OEM Engine: Continental IO-550-N

Empty Weight: 2250 lbs.

Maximum Gross Takeoff Weight: 3400 lbs.

Typical Cruise Speed: 175 KTAS

Standard Fuel Capacity: 81 gal.

Service Ceiling: 17,500 feet

Range: 1049 NM

VS0: 59 KCAS

This article originally appeared in the July 2022 issue of Aviation Safety magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to Aviation Safety!