Airborne Radar Approaches

When an instrument pilot talks about a “radar approach” he usually means one that’s guided by a ground controller using ASR or PAR equipment. But believe it or not, military aircrews have been known to make instrument approaches using their aircraft radar to find the runway. The author made hundreds of these approaches during his military flying career. But don’t try this at home, kids…it takes top-notch radar and a lot of practice.

Many civilian pilots are aware, generally at least, of ground radarsbeing used to guide airplanes to landings through the clouds. The militaryhas used ground control approach (GCA) systems for many years. By the endof WWII and during the Korean War this was an established way of helpingpilots. Radar systems housed in trailers could be relocated to differentairfields, giving the military a world-wide capability despite the vagariesof weather.

Many civilian pilots are aware, generally at least, of ground radarsbeing used to guide airplanes to landings through the clouds. The militaryhas used ground control approach (GCA) systems for many years. By the endof WWII and during the Korean War this was an established way of helpingpilots. Radar systems housed in trailers could be relocated to differentairfields, giving the military a world-wide capability despite the vagariesof weather.

The development of radar systems with precise target-tracking capabilitiesmade GCA techniques possible. Those systems permitted trained radar-scopeinterpreters to guide planes down the glide path toward the runway. Accuraciesto within a few feet in azimuth, elevation and distance (range) to theplane's radar echo made it possible to track and guide it to a safe landing.

When all else fails...

But what about airfields without GCA systems? Or when GCA systems areinoperative? Is there a backup? The answer is "that depends".It depends on two key factors. First, is the airplane equipped with itsown precision radar system? And just as important, is there anybody aboardwho is capable of accurately guiding the plane to a safe landing? In theearly days, neither capability existed, despite the ego-based claims ofradar manufacturers and some radar operators who felt they were the "world'sgreatest".

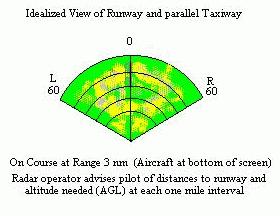

Whilethe GCA operator looks for the radar echo of the incoming airplane, anairborne radar operator must find the end of the runway. Because airborneradar signals striking the runway tend to bounce off and away from thepavement, like a flashlight beam reflected off a mirror, the runway's appearanceon the scope is dark, not a bright dot like the GCA view of a plane. Theairborne operator searches for dark lines and patterns within the clutterof reflecting ground echoes. This can be tough in some situations. Notall military radar navigators and bombardiers could master the airborneradar directed approach (RDA).

Whilethe GCA operator looks for the radar echo of the incoming airplane, anairborne radar operator must find the end of the runway. Because airborneradar signals striking the runway tend to bounce off and away from thepavement, like a flashlight beam reflected off a mirror, the runway's appearanceon the scope is dark, not a bright dot like the GCA view of a plane. Theairborne operator searches for dark lines and patterns within the clutterof reflecting ground echoes. This can be tough in some situations. Notall military radar navigators and bombardiers could master the airborneradar directed approach (RDA).

The accuracy and precision required for an airborne radar directed approachis similar to that demanded for ground-based GCA systems. But it's a tougherjob to reliably locate and track the end of the runway from a moving, bouncingairplane in the weather.

Will this work in my plane?

Could a pilot of a single engine or twin aircraft equipped with a weatheravoidance radar make his own radar approach? Is the radar good enough?And what are the techniques needed to make such an approach?

Theoretically, the answer is a qualified "yes". But in a practicalsense the answer is "probably not". Consider the following factorsbearing upon airborne radar directed approaches. Then compare these againstyour weather radar's features.

-

Your radar equipment must present a high resolution image, an accurateportrayal of the topographical and man-made features in and around theairport. That calls for a narrow radar beam (width under two degrees )to preclude azimuth smearing of the images which could obscure the runway.

-

The radar display should include accurate range markers or a variablecalibrated cursor capable of indicating distances from the airplane tothe end of the runway. It is critical that range is accurately determinedto one-quarter mile or less.

-

Short pulse lengths are also necessary to minimize range measurementerrors. And it is useful to have adjustable gain and contrast controlsto optimize the image for sharpness and maximum detail. Adjustable antennatilt is not important because a narrow azimuth beam pattern often meansa wide vertical pattern anyway. Remember, the target (runway) is not aradar blip. It's the absense of one within the clutter of ground returnsand man-made objects.

-

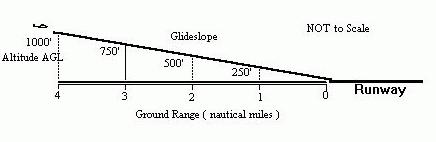

Simple weather radars typically display slant range and not groundrange to the runway. There is a difference. Remember, you're flying downthe glide slope along the hypotenuse of a right triangle, one side beingyour altitude and the other the ground distance to the runway. If yourglide slope is steep the difference between slant range and ground rangeis greater than if the glideslope is shallow.

-

The general procedure requires the pilot to know his ground range tothe end of the runway as well as the heading to steer.At various ranges along the glidepath altitude and speed must be carefullymaintained. Assume, for example, that groundspeed is 120 knots and a descentrate of 500 feet per minute is practical for your airplane and airfieldobstacles.

At five miles from touchdown you must be at 1250 feet AGL andon course. Touchdown is just 2.5 minutes away. At three miles out you mustbe at 750 feet and at one mile 250 feet AGL. All the while you must keepon course, aligned with the runway.

At five miles from touchdown you must be at 1250 feet AGL andon course. Touchdown is just 2.5 minutes away. At three miles out you mustbe at 750 feet and at one mile 250 feet AGL. All the while you must keepon course, aligned with the runway. -

As the range to the runway diminishes the radar image of the runwaywidens and smears. Close-in ground clutter brightens because echoes getstronger. You may detect the edges of the runway, the rough surfaces whichreflect back toward you. The smooth runway itself will remain dark becausereturned echoes are absent.

Tougher than it sounds

It's a lot of work to fly the airplane precisely, maintaining courseand glideslope while holding speed constant. Altitude at each range markis crucial. There's no opportunity for one pilot to do all this while constantlymonitoring the ever-changing radar images. It takes two people, a skilledradar operator and a capable pilot.

What weather minimums should apply to this technique? In the above examplea 500 foot ceiling gives the pilot just one minute to transition to a visualapproach and landing. At lower ceilings the time gets much shorter andthere's not enough time to make last minute corrections. You're down tojust seconds.

What weather minimums should apply to this technique? In the above examplea 500 foot ceiling gives the pilot just one minute to transition to a visualapproach and landing. At lower ceilings the time gets much shorter andthere's not enough time to make last minute corrections. You're down tojust seconds.

Equipment in many military bombers and fighters is accurate enough tomake such approaches possible. Crews must practice to master the techniquesand to perfect the coordination required.

Should others with less capable radar systems or no RDA experience trythis? Even in an emergency situation? Not really. That's what alternateairfields are for.