Dude! You’re Busted!

AIRMET Tango for turbulence was spot on. You’re given “climb and maintain six thousand,” but with the bumps you accidentally enter 7000 in the altitude preselect. Passing through 6,300 feet,…

AIRMET Tango for turbulence was spot on. You’re given “climb and maintain six thousand,” but with the bumps you accidentally enter 7000 in the altitude preselect. Passing through 6,300 feet, you hear your call sign and, “verify level at six.” You stop the climb and head back down. All seems good until 10 minutes later you hear your call sign again. “Possible pilot deviation. Advise you contact Chicago Center Quality Assurance. I have a phone number. Advise ready to copy.”

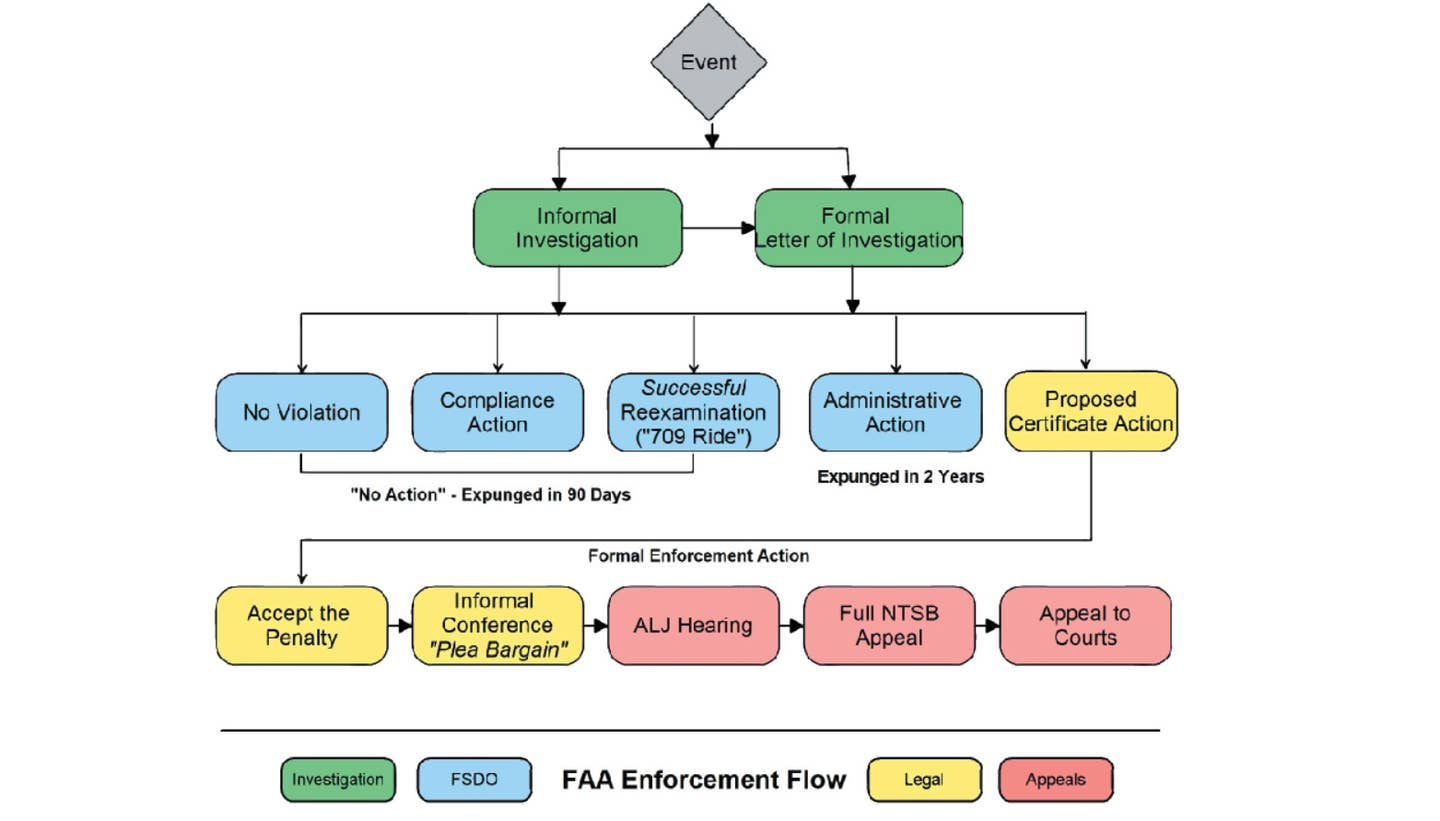

I think of the FAA enforcement process as having five distinct phases: the triggering event, investigation, resolution at the FSDO, enforcement, and appeals. My goal is to give you a basic understanding of the process so, if it happens to you, it won’t be a surprise.

The Event

The event is a claimed deviation. “Busting” altitude, our example, is the most common airborne one. But they aren’t limited to flight activities. You could bust a ramp check, or perhaps there’s a “grey charter” hurting a certificated operation. A customer might complain about a mechanic. Or, the YouTube video of your expert buzz job. All can trigger an investigation.

We hear “possible pilot deviation” if ATC thinks we didn’t follow instructions. This is a “Brasher warning.” The name comes from 1985 when Captain Jack Brasher deviated from his assigned altitude. ATC didn’t give him the advisory, which was added to the controller manual earlier that year. On appeal, the NTSB agreed that there was a violation but removed the certificate suspension. The NTSB referred to some of the FAA’s reasons for adding the warning. Early notification allows the pilot to learn what ATC says happened and “prepare his notes for response to the allegations.”

Thus, the Brasher rule is a violation on the pilot record but there’s no certificate suspension unless the warning is given. There are limits. It’s workload permitting. For another, one case refused to apply the rule to a pilot who departed a towered airport without a takeoff clearance, treating it as an en-route rule. But those distinctions are rarely made by controllers. Normally, a pilot who deviates from an ATC clearance will receive a Brasher Warning as a prelude to an investigation.

Sometimes talking with ATC is the end of it, particularly if there was no significant threat, or safety hazard. That’s not always the case. But pilots can make the call, listen to what ATC has to say, and limit their talking to contact info.

Investigation

Next, an Aviation Safety Inspector (ASI). will open a file, review reports, speak with witnesses and (usually) contact the airman through a formal Letter of Investigation, by telephone, or e-mail. Both formal and informal contact should include notice of the right not to respond and will supply information about the Compliance Program.

Resolution By The FSDO

Regulatory deviations can be resolved in one of four ways within the investigating FSDO. (1) An investigation can show there was no violation. (2) The airman can be given a “709 Ride.” (3) There can be what the FAA calls “administrative action.” (4) Now most common, is a “Compliance Action” under the Compliance Program.

A “709 Ride,” more formally, “Reexamination,” comes from the FAA’s authority (49 U.S.C. §44709) to “reexamine an airman holding a certificate” when the FAA has reason to believe the conduct indicates a lack of competence. The most common example is the follow-up to a gear-up landing. They are generally targeted to specific conduct and an overly broad 709 can sometimes be negotiated into something more limited. A pilot faced with a 709 ride may move it to a FSDO other than the one that did the investigation, and it should go without saying that getting good instruction before the checkride is highly recommended. A successful 709 falls into the “no action, no violation” category. But an unsuccessful ride or refusal to do it invariably leads to the FAA moving to revoke certificates and ratings.

Administrative Action

There are two types of Administrative Actions—Warning Notices and Letters of Correction. Technically different, they can overlap. The Warning Notice essentially says, “We have evidence you did something wrong, but we are using our discretion not to violate you. Don’t do it again.” The Letter of Correction does the same but includes specific steps to correct the problem.

The Compliance Program

In June 2015, the FAA announced the Compliance Program (originally “Compliance Philosophy”). Information about the program is at https://www.faa.gov/about/initiatives/cp.

The program’s philosophy begins with the premise that regulatory compliance is more likely to be achieved by “an open and transparent safety information exchange” between the FAA and airman than by the threat of punishment. The goal is to identify the causes of deviations and try to correct them. Like the Letter of Correction, the airman must “acknowledge responsibility and take corrective actions,” but both the process and the consequences are different. A Compliance Action may involve informal counseling by telephone up to formal and targeted training. In exchange, a successful Compliance Action is considered “no action.”

The “Compliance Action” is the FAA’s first choice for handling deviations that are not intentional, reckless, or fraudulent. Cases commonly accepted in the past for certificate action have been returned with instructions to handle them under the program. In the five years since it began, the Compliance Program has been fairly successful. We’ve seen in-flight deviations and presidential TFR incursions end with pilots proactively getting training followed by a short discussion with the investigator.

Is It On My Record?

The four FSDO-level dispositions—see chart—are not considered violations on the pilot’s permanent record and allow you to say you’ve not been found to violate a regulation. For the career-oriented, they are not reportable under the Pilot Records Improvement Act, although they might be discovered by FOIA and Privacy Act requests until expunged.

The FAA maintains a system to track all deviations that are investigated. Expunction removes identifying information from those records after certain periods of time. “Violations,” the final result of the formal enforcement process described below, are never expunged. Non-violations are. “Administrative Actions” are expunged in two years. Those falling into the FAA’s “no action” box—including successful 709 rides and Compliance Program completion—are expunged within 90 days.

Formal “Enforcement Action”

The FSDO assigned to an investigation follows a flow to decide if the Compliance Program is appropriate. If the FAA considers the conduct intentional, reckless beyond the definition in §91.13, or fraudulent, or the airman resists or fails to comply with the program, the case can be referred to the FAA’s lawyers for formal enforcement action.

The formal enforcement process begins with a “Notice of Proposed Certificate Action” describing the alleged conduct, the regulations violated, and the proposed penalty. The recipient can accept the penalty or go directly to the appeals process. Far more often and almost invariably if the airman is represented by an attorney, there will be a conference with an FAA attorney. At best, it is an opportunity to convince the FAA lawyer there was no violation (it happens). Usually, though, it is an opportunity to “plea bargain.” The airman’s filing of a NASA ASRS report is often discussed to avoid the penalty (but not the violation record). But by this point, the FAA has probably decided the pilot’s actions do not meet the “unintentional” standard for ASRS penalty waiver.

If no settlement is reached, the FAA issues a final Notice of Certificate Action, revoking or suspending the airman’s certificates for a certain length of time. For a pilot, revocation means starting over. Logged time remains, but checkrides must be taken and passed again, typically after a year, to regain lost privileges. In the extreme, the FAA can bypass the Notice-Conference stage entirely, taking action to revoke certificates immediately on an emergency basis.

Unlike Administrative Actions that are expunged in two years, a formal violation remains on the pilot’s record for life, whether or not there was also a suspension or revocation.

Appeals

The airman can appeal the certificate suspension or revocation. The NTSB is the first “court of appeals” for FAA certificate actions. It is a formal two-step process. A trial takes place before one of four Administrative Law Judges (ALJ), without a jury. If the airman or the FAA doesn’t like the decision, either can appeal to the full NTSB. If dissatisfied with the full NTSB ruling, either can appeal into the Federal Court system. Each level of appeal is more limited than the previous one. The ALJ decides the case based on witness testimony and other evidence. The full NTSB review is aimed primarily at legal interpretation with no witnesses or new evidence. The federal court is even more limited, primarily interested in correct application of the law, the authority of the FAA to take certain actions, and constitutional issues.

Lawyer Up?

I’ve avoided giving advice about what to do. Each case is different. The right answer in one may be the wrong answer in another. Even before the Compliance Program, the often-quoted advice to ignore and say nothing was suspect. Take our scenario pilot in an IFR aircraft tracked on radar with a deviation memorialized by both radar and ATC recordings. Especially with the Compliance Program, the main effect of stonewalling can be to raise suspicion and make things worse.

But that does not mean going it alone. The biggest potential problem for an airman isn’t admitting what the FAA already knows. It is saying the wrong thing, admitting more than one has to, which opens another—perhaps more serious—inquiry. Trying to be “cute” and uncooperative, or perhaps a wise guy, doesn’t play well. Many airmen have successfully negotiated the system on their own, but this is where good advice from an aviation lawyer before speaking with an ASI can be valuable, not as a mouthpiece doing battle, but as a knowledgeable advisor to help navigate an unfamiliar system.

Here’s a real-world example. The FBO at a nontowered airport radioed a local pilot doing touch and goes. “Better land and come in here. The FAA is on the phone.” Picking up the phone, the pilot learns there was a presidential TFR in effect over the airport. His lawyer’s advice? Contact an instructor, do a ground session on the importance of preflight briefings, even if remaining local. Log the instruction.

The result? When the FSDO telephoned him a few days later, the pilot told the ASI what he had done and presented his logbook entries showing his proactive response. The ASI was satisfied and closed the case.

Mark Kolber is a CFI/CFII and aviation lawyer who insists the best results come when the FSDO doesn’t even know he is involved.

For more great content like this, subscribe to IFR!