Coming Back

Every so often I’ll get a casual inquiry from a “usta” pilot, someone who has a pilot’s license but hasn’t flown for a long time. Quite often, they’ll have an…

Every so often I’ll get a casual inquiry from a “usta” pilot, someone who has a pilot’s license but hasn’t flown for a long time. Quite often, they’ll have an instrument rating and several hundreds, or even thousands, of hours of professed time. The conversation will start with “I used to fly, quite a bit. Just wondering what it would take to get back in the air.”

I think they already know the basic answer: Study up, get into an airplane with an instructor, go out and rebuild skills. Initially, I encourage them with “Let’s go do it; you probably remember more than you think.” I don’t want to make flying sound more challenging and tougher than it used to be, even if it has gotten more complicated in some ways. We need all the pilots we can get, and it’s easier to brush up a former aviator than to create a new one from scratch.

But, what do I usually find when I start scrubbing off the layers of rust and moss? Depending on the lapse of time and the pilot’s past experience, the skill required to fly an airplane can come back rather quickly. The age of the individual is definitely a determining factor. We don’t like to admit it, but learning— and relearning—comes slower when we’re older. That doesn’t mean it can’t be done or that it shouldn’t be encouraged. Once acquired, an older person’s skills are as good as anyone else’s, particularly when based on experience.

Motivation is the key. If the returning pilot is willing to put forth the effort, he or she will be able to get back into aviation in some fashion. However, I’ve found that in a lot of cases, these former pilots are just curious, and once they’ve satisfied themselves that they can still move an airplane around the sky, they often leave the airport, never to return. If they experience a touch of frustration when they take the controls for the first time in a decade, they will probably fail to continue the pursuit. I try to prepare them for this by softening the impact, and I’ll seek an opportunity to brag them up a bit. I’ll say something like “You’re just rusty, as expected; your altitude control proves you’re still a pilot.”

When it comes to regaining currency, each case has to be evaluated individually. Because skills and knowledge must be matched to the ratings held and privileges sought, we can’t just quote a standard course and shove someone through the curriculum. The goal of bringing back a pilot is not to complete a flight review; it’s to make the pilot thoroughly comfortable in the aircraft, like they were before their layoff.

The Homebuilder as Pilot

One repository of rusty aviators is, all too often, found within Experimental/Amateur-Built workshops. As our EAA chapter’s official flight advisor, my name shows up in a database of such safety-enhancing volunteers. Our job is help pilots decide how they should handle a move into a new-to-them airplane, perhaps even one involving the first flight of a just-completed homebuilt. This frequently results in a recommendation to have somebody with more current and relevant experience make the first flight or do the ferry trip to fetch a new acquisition home.

Why? Because often the owner/ builder/pilot hasn’t been flying regularly and has limited experience in the category of aircraft they are about to tackle. Homebuilders in particular may spend years investing all of their spare time in their project and, most recently, have been working hard on finishing up that last 10% that always takes up half the building time. Their flying skills have deteriorated, and they may not even have had access to an airplane during their absorption with the project. Bringing them back up to full currency is not a quick and easy matter.

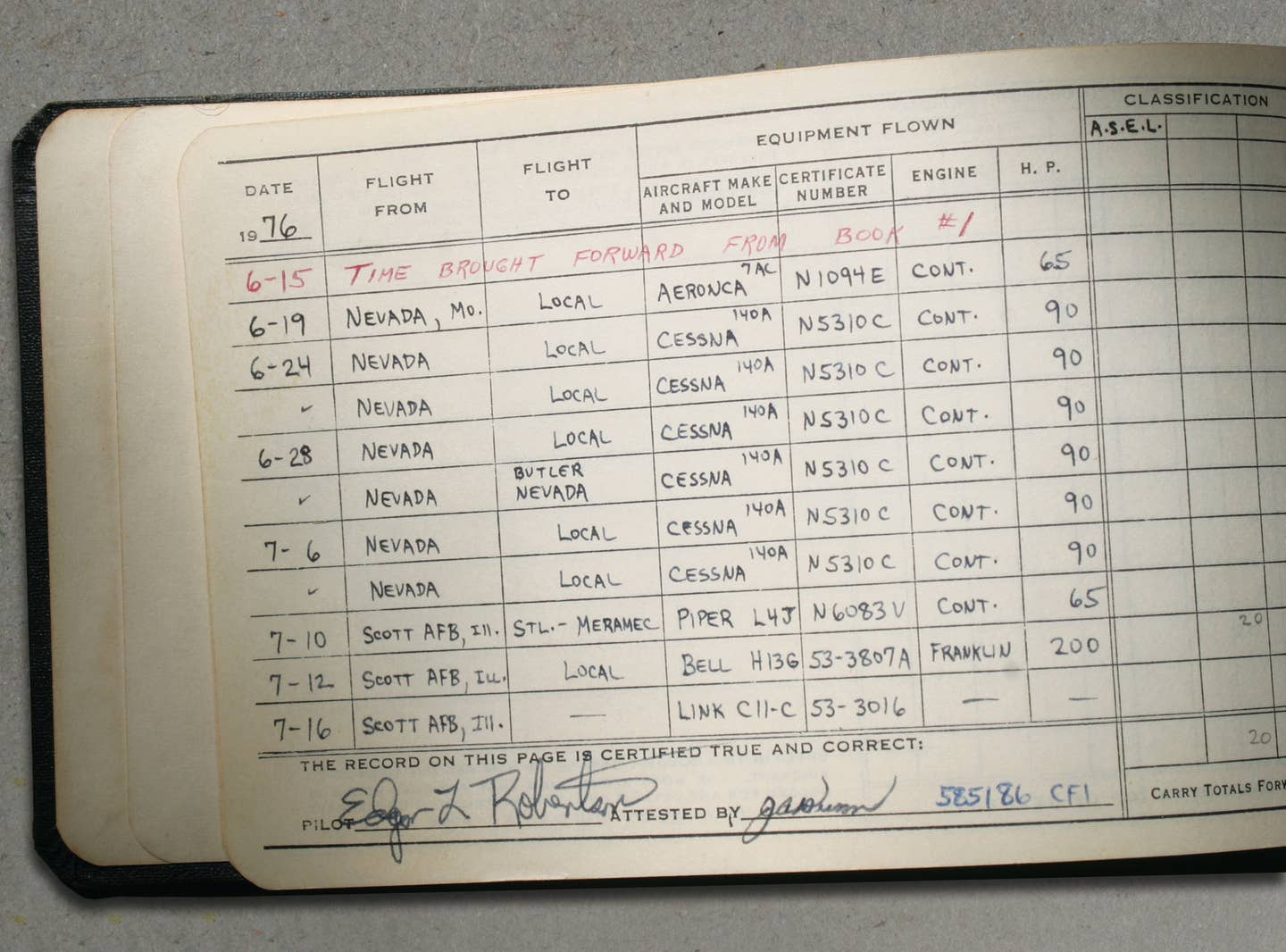

“But I just had a flight review in a 150 last week. Doesn’t that make me legal to fly my Baby Belchfire?” Legal, maybe, but not necessarily advisable. When we look at the pilot’s logbook, we find about 10 hours logged in the last 10 years. “Better spend some time with a CFI and get some dual in an airplane more similar to the little Belchfire,” I have to counsel.

What to Expect During Training

I always advise instructors to start simple when restoring a pilot. Everybody wants to try their hand at landings, but what most people really need is practice flying the climbs, descents, and turns inherent in a traffic pattern, so they can keep up with the aircraft as it nears ground level. Speed and configuration transitions, as when slowing from clean, level flight to a final approach condition, should first be undertaken at altitude, simulating the traffic pattern and mastering trim changes.

Where most returning pilots falter is in managing the aircraft while taking care of the other piloting chores: maintaining situational awareness, obtaining and following ATC instructions, remembering to switch fuel tanks, and actuating controls on schedule. That’s what we’ve always termed “getting behind the airplane,” and it takes a while to start thinking and acting as fast as the airplane is moving.

The overriding task is not to condense a learning-to-fly course into fewer hours than you experienced as an initial student. Don’t cut it too short. It’s important to spend enough time with your instructor that you settle back into your old routine of flight management. Each individual requires something slightly different. It takes an innovative instructor to tailor a brush-up course to suit all the different former pilots.

Of course, the goals are the same as with any pilot seeking certification or recertification. There are tolerances that must be met, judgment that must be demonstrated, and procedures that must be followed. Use of checklists has to be stressed, even though the pilot is drawing on earlier years of experience. In the stress of battle, things can get overlooked, which is why a prepared checklist is needed to back up one’s memory.

It is also highly important to receive updated instruction in modern procedures and requirements, not just in flying itself. Ground training should be planned on about a 2:1 ratio with flight time, if for no other reason than to permit some hangar-flying discussions. Former pilots bring a wealth of experience to the table, so if a topic sparks an “I remember the time…” response, let it flow, but make sure you understand that it may need to be modernized to fi t today’s nomenclature. Make sure you’re familiar with current ATC expectations: full read-back of instructions instead of “roger,” use of line-up-and-wait rather than position-and-hold, making reference to arrival and departure procedures instead of SIDs and STARs.

Making a Connection

It’s important to connect the old with the new. What used to be a TCA is now Class B airspace, and the former airport traffic area has become Class D airspace. Self-briefings of preflight weather and NOTAM acquisition have largely replaced calling Flight Service, with many more sources of automated weather available, even in flight. There’s no more Flight Watch available on 122.0, and you’ll need to figure out the arcane ICAO flight plan format, which takes a bit of study.

Most former pilots can quickly adapt to iPad and smartphone applications, once they see how it makes their life easier. Keep it simple, however. Just learning to use the basic planning and navigation functions is enough to start with, and many older pilots often want to keep paper charts and flight logs in the cockpit, at least for a while. It only takes one locked-up electronic flight bag from excessive heat, battery depletion, or GPS interruption to make one realize the importance of backup capability.

Expect to be challenged with probing questions. To check understanding of the fuel system, for example, I like to ask how the pilot will manage fuel burn, switching tanks, and keeping a running tally of how many hours and minutes of fuel remain.

Often a rapid brush-up isn’t enough to ensure a pilot is retaining information, so I sometimes cover material using multiple techniques. For example, after a brief discussion about communicating with ATC, I’ll say something like “Let’s role play the contact and conversation you’ll have with a control tower as you fly in and out of a Class D airport. I’ll be the controller.”

A former pilot is a surprise waiting to be unwrapped. Each one is different, and each requires specialized handling. A 20-year gap in flying is different from a five-year lapse, and an ex-fighter pilot is a different animal from a retired airline crewmember. I’ve learned not to stay relaxed when the aircraft nears the runway on final approach, just because the returning pilot has done well while performing maneuvers at altitude. The tenseness of wanting to do a good landing can translate into beginning the flare at 50 feet AGL, which will result in a power-off sink rate well beyond the landing gear’s absorption ability. Pushing the yoke forward at an inappropriate moment is a common response, as is leveling off at a cockpit height more typical of a DC-9. I’ve learned to stay alert when the pavement is near.

I also don’t assume that a former pilot still knows the basic rules of the road, so I verify regulation knowledge with quizzes and situation set-ups. It’s better to find out the pilot’s missing information while sitting in the pilot’s lounge than in a busy cockpit with ATC pointedly requesting a phone call upon landing.

Not All at Once

I must stress, repeatedly, that returning to flight status is a gradual phasing-in, not a stamp of approval for all operations. It makes a big difference what kind of airplane is going to be flown and what kind of flying the former pilot will be doing. If an LSA is going to be the plane of choice, instilling respect for loading and wind conditions, rebuilding basic control skills, and doing some local flying or a short cross-country flight might be enough. If, on the other hand, the pilot wants to enter a complex kit aircraft ’s cockpit, I often suggest a transition into high-performance airplanes with similar characteristics, plus some mentored flying with a current pilot familiar with the type.

The legalities must not be overlooked. Even to fly simple airplanes, a flight review endorsement must be placed in the logbook. An instrument proficiency check (IPC) should not be sought at the same time. Flight reviews are an attestation of basic flying skills and knowledge, while the IPC goes off in a different, more-specialized direction. It’s better to fly day VFR at first to regain cockpit composure, followed by the instrument-flying signoff at a later time.

I always check for a pilot license and medical certification. I still run into pilots who haven’t acquired the required plastic card or who haven’t a clue as to where their old pasteboard certificate can be found. They may need to apply for a replacement certificate using their current address, and if their medical certificate isn’t up to date, an appointment with an AME has to be set up. The new BasicMed option doesn’t apply if the pilot’s last medical expired more than 10 years ago, and even if the pilot is qualified to use BasicMed, a visit to a doctor to have the required exam will be needed, along with completion of the medical training course. Documentation of these BasicMed requirements must be maintained with the pilot’s logbook.

Can an inactive pilot come back? Of course. It’s just a matter of evaluating the potential hiding under those layers of rust and making a plan to brush them off. A pilot license is a terrible thing to waste, so let’s encourage all former pilots to get back into the air.

For more great content like this, subscribe to Kitplanes!