To Autopilot Or Not

Most of us think of the autopilot as a modern invention, but it predates World War I. That perception may be because it has only become ubiquitous in more recent…

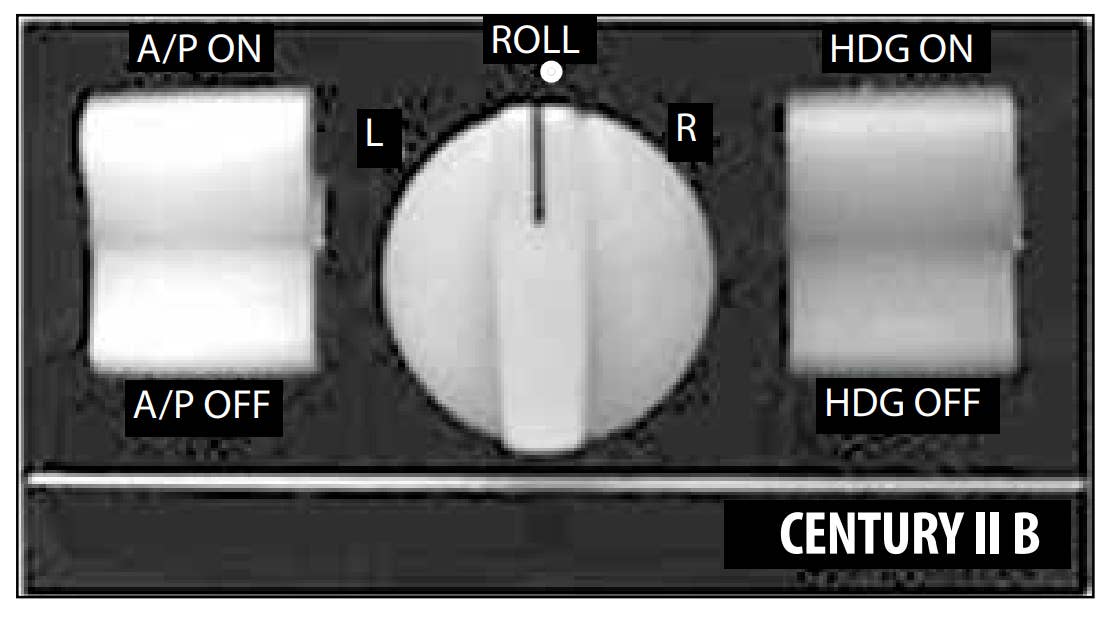

The autopilots available to light aircraft of days past were rather simplistic and easy to use.

Most of us think of the autopilot as a modern invention, but it predates World War I. That perception may be because it has only become ubiquitous in more recent times.

All IFR pilots take pride in their manual instrument flying skills, and rightly so. Smoothly and exactly maneuvering an aircraft down the ILS to minimums is an intensely satisfying experience. Of course, modern autopilots do this (in most cases) just as well, and often better, than the human pilot.

The Automation Syndrome

There has been debate in the airline industry whether all the automation has caused a deterioration in piloting skills. The answer is an unequivocal yes.

I have many thousands of hours successfully hand flying light singles and twins through all sorts of weather. Like most things in life, you get used to it. The difference, however, from what may have been the norm 20 or 30 years ago, is the significant step-up in the performance of the new breed of GA planes.

Bumping along in the soup at 5000 feet in a piston single at 120 knots is a whole different ballgame than cruising in the flight levels in one of these popular turboprop singles such as the TBM or Pilatus going more than three times as fast—not to mention jets.

So, while many of us may mourn the demise of basic instrument skills, everyday use of autopilot is now a fact of life. Autopilots come in all shapes and sizes, from the humble wing leveler installed in many old Pipers (that rarely worked) to airline-grade equipment managed through a flight guidance panel. Regardless of sophistication, there is a lot to learn. You can argue about when and where to use automation, but it depends on your preferences, skill levels, and what’s installed in a panel.

Turning It Off

Let’s discuss when not to use our friend “George,” and one often overlooked aspect—how to turn it off. Yes, autopilots have been known to attempt some aerobatic maneuver requiring prompt intervention on occasion. So, it’s imperative to understand (and memorize) the several ways to disconnect.

- First, a modern installation has a disconnect button (often red) on the yoke.

- Second, there’s an off button on the autopilot panel itself.

- Third, somewhere on the panel there’s a circuit breaker likely labeled AP that you can pull.

There may be others too, like in my daily ride, running the pitch trim. Of course, when all else fails, you can always physically overpower the autopilot servo. But you wouldn’t want to play that game for too long.

Now that we’ve discussed how to kill the beast (should we need to) let’s establish how you will be warned if the thing dies on its own. An Eastern Airlines 1011 was lost this way when the crew failed to notice the autopilot having kicked off. Should this happen in the airplane I fly, there’s a nagging voice saying “autopilot” until I acknowledge. Yours may have a warning light, or maybe nothing, in which case OFF may be the best choice.

When Not To Use

When is intentionally turning the autopilot off a good idea? Usually in significant turbulence. The premise is that it tries to pitch aggressively to maintain altitude, therefore possibly allowing too high or low airspeed to develop. Hand flying would attempt a constant pitch while allowing altitude to vary—and advising ATC of the situation. In theory, this is good advice. However, there are a few “buts” in there.

As mentioned, the size and performance of aircraft, as well as the level of avionics sophistication in the GA fleet varies immensely.

If you find yourself in that dreaded “borderline severe” turbulence, and the AP in your particular aircraft is doing a decent job of keeping the proverbial shiny side up, why change that situation? Use power to maintain speed as close to the recommended for turbulent air as you can, report to ATC (when able), and hopefully you’ll be out of it soon.

Of course, some autopilots disengage on their own when turbulence goes beyond light to moderate. If you know this is the case, be proactive, turn it off, and hand-fly before that happens.

On The Approach

Another time when hand flying quickly becomes necessary is on an ILS if the needles become unstable. This happens more frequently than you might think and may be caused by an airplane taxing in front of the localizer antenna or maybe the tractor mowing the grass getting too close to the glide slope shed. The result can be a rapid, wide swing of either needle with the autopilot blindly trying to follow.

Your best and safest option is to immediately click off the AP and maintain whatever heading and pitch you had. Most likely, the disturbance is only momentary, and you can continue the approach. Re-engage the AP if so desired. However, I’d be leery of the whole situation and keep hand flying. If you lose guidance for more than a few seconds, the only safe option is to perform a missed approach.

Sometimes an approach gets messed up through no fault of either the navaid or pilot. ATC may leave you high and dry above the glide slope instead of below it as you near the final approach fix.

If on AP, you may have to select a (high) vertical speed down for the system to hopefully get back on profile. This is fraught with risk as you should never have a high descent rate at low altitude in IMC. Should the guidance fail to capture the glideslope (and it may not from above), the plane may head for the terrain short of the runway.

Better to again demonstrate your superior flying skills. It’s much easier to manually moderate pitch and power for just that correct amount of extra descent required to get back on glide slope without overdoing it. And you should be ready for a missed approach if that becomes the best and safest option.

On approach, even light turbulence (such as caused by convection or gusty winds) can easily trip up an autopilot. This time the issue is not a loss of control but more a question of comfort.

Reactive Versus Proactive

Any autopilot, no matter how advanced, is reactive. The system senses a deviation and then applies a corrective control input. How quickly and how precisely varies.

The skilled human pilot, however, is instinctively more pro-active and should anticipate. If you sense a downdraft, you’ll probably add power to counteract it before the glideslope needle moves upward. The same goes for a disturbance in roll, causing a lateral deviation.

The result, if done well, is a smoother ride to higher tolerances than what old “George” can sometimes accomplish.

Finally, no matter how knowledgeable and skilled you are in the various systems and their use, complex often means complications.

There are many situations, especially when you are starting to feel stressed and risk falling behind the airplane, where just hitting the off button and reverting to basic instrument skills is the best solution. It’s always the most satisfying one.

Bo Henriksson is a captain with a regional carrier and has more than 20,000 flight hours.

This article originally appeared in the May 2020 issue of IFR Refresher magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to IFR Refresher!