Deal With Distractions

Many of life’s distractions are enjoyable, but cockpit distractions can have tragic consequences. For years, the NTSB has made “Eliminate Distractions” one of their Ten Most Wanted safety improvements. In…

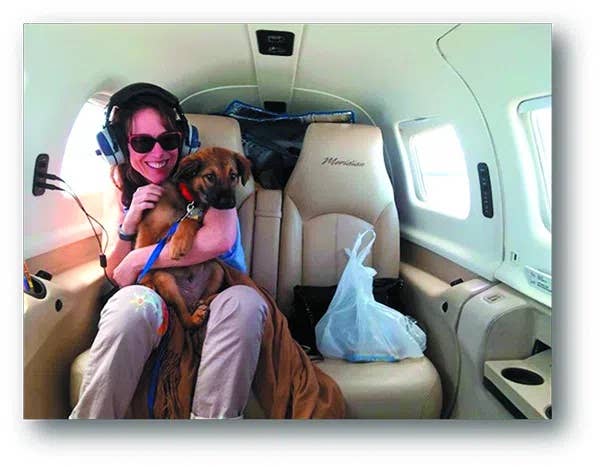

We all love our pets, but unless you know your pet will be well behaved and not present a distraction, it might be best left at home.

Many of life’s distractions are enjoyable, but cockpit distractions can have tragic consequences. For years, the NTSB has made “Eliminate Distractions” one of their Ten Most Wanted safety improvements.

In Ernest Gann’s Fate is the Hunter, he describes a night approach as a DC-2 First Officer while Captain Ross lit matches in front of Gann’s nose to distract him. Ross later made the famous statement, “Anyone can do this job when things are going right. In this business, we play for keeps.”

Of course, that’s pretty extreme, but even innocuous distractions can seriously get in the way of a safe flight.

Personal Experience

As a young adult we traveled a lot, so I got checked out often and flew with a lot of different flight instructors. Some used distractions to make a point. Two of these I still remember to this day. The first one was while I was attempting a short field landing. When I turned base to final, the instructor popped the door open on the Piper Cherokee. It was not the prettiest of landings, but I kept it under control by remembering to fly the airplane. (The flight instructor wouldn’t have had much time to react if I’d failed to fly the airplane!)

The second was on a VOR approach under the hood. The instructor asked me about something on his side of the aircraft and when my attention was diverted, he changed the VOR frequency. It was one of the rare times where I had the needle centered. When he changed the frequency the needle stayed centered, but the flag appeared. I missed the flag. I flew for several seconds before realizing that I did not usually go that long with a centered needle. It was a good lesson.

Passenger Distractions

However, the biggest surprise distraction wasn’t from an aircraft or ATC issue but from my passengers. Shortly after getting my Instrument rating, my wife and I took a trip from Greensboro, North Carolina to Lynchburg, Virginia in a C-182. The trip up was fine, but weather had moved in for our return trip. It was “easy IFR” with a fairly high ceiling but there was light to moderate turbulence in the clouds.

My wife had flown with me many times VFR, but as soon as we entered the clouds and encountered some bumps, she got nervous saying “I don’t like this.” “I want to go back.” “Can’t we land?” I was really surprised, and it upped the workload trying to keep her calm while, indeed, flying the airplane. The airplane didn’t have an autopilot to help with the mundane stuff like keeping the dirty side down. On later instrument flights she became used to the environment and was fine. Digressing, even on commercial flights, I told her unless you hear me say “Oh $#^+” everything is fine … but that’s another story.

The second passenger distraction surprise was with my young son. When the weather was “nice IFR” with stratus and moderate ceiling with good visibility underneath I would often go up and shoot some approaches. The aircraft I selected this particular day was a Grumman AA-1B.

The AA-1B is sensitive in all axes, which makes flying a localizer approach (no glideslope in this low-cost rental) that much more of a challenge. I took my three-year-old son along. Like my wife previously, he had flown with me before and I did not think anything about it. Well, the same thing happened, but this time it was crying and screaming. Instead of shooting three approaches, it was one and done for the day. He didn’t fly with me again for several months. (I’ve since learned to be sensitive to my passengers’ comfort levels, even if they are but three years old.)

Accidents

Probably the most famous accident that was attributable to a distracted crew happened to Eastern Airlines Flight 401, a Lockheed L-1011. It crashed into the Everglades in December 1972. The flight was from New York to Miami.

On the approach to Miami, the crew noticed they had an unsafe landing gear indication. The crew diverted to an area west of Miami to troubleshoot the problem. They engaged the autopilot in altitude hold but in the process of troubleshooting, they did not realize that they had disengaged altitude hold by inadvertently bumping the control column on the captain’s side. This caused the autopilot to change the mode to Control Wheel Steering and initiated a slow gradual descent into the Everglades.

The NTSB finding was the accident was caused by the “failure of the flight crew to monitor the flight instruments during the final four minutes of flight, and to detect an unexpected descent soon enough to prevent impact with the ground. Preoccupation with a malfunction of the nose landing gear position indicating system distracted the crew’s attention from the instruments and allowed the descent to go unnoticed.”

Closer To Home

There was an accident that was close to home, above our house in Exton, PA. I was doing some interior work on our house on an overcast day in July 2004. We heard an aircraft pull out of a dive and my wife joked, “Are they dive-bombing us?” Not thinking too much more about it I went back to work. Only a few minutes later I heard sirens from several emergency vehicles. While the pilot managed to pull out of the dive over our house and level out, he hit a house on a ridgeline less than a mile away. The instrument-rated private pilot and his female passenger were killed.

The NTSB report indicates while he had limited experience in IMC (11.9 hours) he appeared cocky—my words—at the departure airport, Chester County, PA (KMQS). A witness observed the airplane (a Piper Warrior II) depart and approximately 50 feet above the runway, it disappeared into the clouds.

The pilot contacted ATC and was cleared to 4000 feet with a 090 heading. Four minutes later he reported climbing through 3200 feet. Two minutes after that he was given a left turn to 050 degrees that he acknowledged. After that things when awry. He could have lost instrumentation, but he did not report that to ATC.

The NTSB report states that the attitude indicator and directional gyro instruments revealed rotational scoring on their gyro casting and gyro housing [indications that they were functioning on impact.] The NTSB probable cause finding states: “The pilot’s failure to maintain aircraft control in instrument meteorological conditions, which resulted in the airplane impacting a residence. Factors in the accident were the pilot’s lack of recent instrument experience.”

That is a straightforward conclusion, but I have always wondered if his companion had the same issues being in the clouds as my wife had. Did she hear the conversation at the departure airport about the “nasty stuff” along their route of flight? Had she been with the pilot on previous instrument flights? Was he acting overconfident and she knew it? Finally, was she an extra distraction that pushed him beyond his capability to handle all the tasks? We will never know.

Managing Distractions

After multiple accidents caused by distracted crews in the 1970s, the airlines and FAA came up with Crew Resource Management (CRM). One of the biggest aspects of CRM was a “sterile cockpit” where there is no extraneous communication while taxiing or anywhere below 10,000 feet. It even became an airline regulation (§121.542). Since instituting CRM, airline accidents have dropped significantly.

By substituting “cruise” for “10,000 feet,” it is also a good rule for general-aviation pilots. Passengers should be briefed on the sterile-cockpit concept. Also, explain to your passenger(s) that an IFR flight requires more communication with ATC. They should be briefed that if they hear the controller say the aircraft’s call sign they should stop talking. They should not resume the discussion until the ATC communication has been completed.

If the right seat passenger has not flown in IMC in a light aircraft, you should also do a quick overview of what to expect. Discuss the inner ear sensations that the passenger could feel as the aircraft is turning when it is straight and level. Discuss the instruments, especially the attitude indicator, to help them see what the aircraft is doing. If the flight is going to be bumpy tell them so in advance.

Distractions from ATC can also be managed. On an instrument departure in IMC, don’t rush to respond to ATC. You have a lot to do on the takeoff and initial climb. Take the time to get the aircraft configured correctly before communicating with ATC.

If ATC gives you a complicated routing change and you are extra busy hand flying in turbulence, try negotiating to keep the original route or ask for a heading until you have time to handle the new route. If they have been in your situation they will understand.

Distractions from avionics can be managed by doing more up-front planning and preflight operations. Have your flight plan on a storage device such as an iPad to allow easy loading into the airborne system. We’ve all asked: “Why is it doing that?” Rather than getting distracted trying to diagnose an avionics issue disengage and fly it manually.

But, in spite of all our cautions, some distractions will still pop up. Try to keep yourself focused on the job at hand, ignoring the distraction. If it’s a passenger, try just raising your hand in a “wait a moment” gesture.

Epilogue

If you are a new instrument pilot, you should consider who you are going to ask along on an instrument flight in IMC. Also, it would be good to brief the passenger(s) on what they might expect and how to read the attitude indicator. The motto “be prepared” helps, but fly the airplane is imperative.

For more great content like this, subscribe to IFR!