Post-Repair Flights: Recognize The Risks

All things being equal, accident data reflect that we pilots are pretty good at dealing with the risks involved with repeatedly causing inanimate objects to leave the ground, move through…

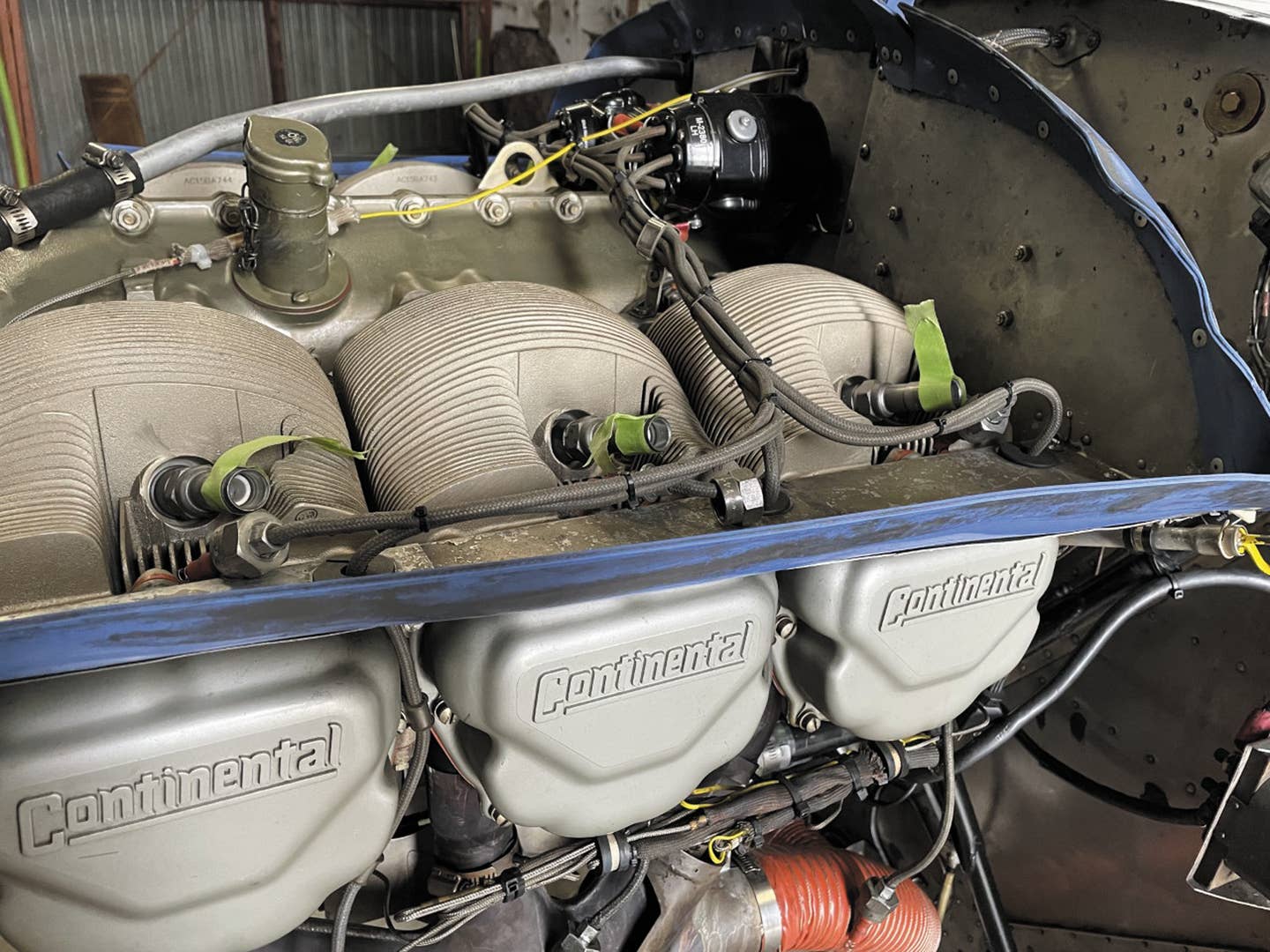

Hey, it’s just a routine annual and those are new spark plugs—what could go wrong? Let’s see, those are new spark plugs, the airplane has been opened up and left in a storage hangar waiting for parts and it’s being worked on by humans—what could go wrong?

All things being equal, accident data reflect that we pilots are pretty good at dealing with the risks involved with repeatedly causing inanimate objects to leave the ground, move through the air and land. Unfortunately, things are not always equal, and the factors that make us human, such as stress, distraction and impatience, can conspire to elevate the risks involved with a given flight to the point where the return to the planet is not as intended.

The very good news is that when we are conscious of high-risk circumstances, most, beyond the “hold my beer and watch this” set, are mature enough to act to reduce the risk to an acceptable level.

Accident numbers show that some of the highest risk flights are the first ones after the airplane comes out of the maintenance shop—from any type of maintenance, even the most prosaic oil change. It’s a combination of infant mortality for new components and human error by maintenance technicians.

Human Error? A&Ps?

The reality of the risk of post-maintenance flights started to become real when I looked at the accident photos of a pressurized piston twin that had suddenly dived vertically into the ground on its first flight out of the shop. One of the accident investigators showed me the signatures of elevator flutter on components of the tail. He also showed me the open space where the elevator balance weights should have been.

As with most accidents, it was a result of cascading human mistakes. A tug-operating lineman had backed the airplane into a post, wrecking the elevator. The shop that painted and installed the replacement elevator somehow forgot to balance it—and install the balance weights.

The pilot who was to “take it around the pattern” didn’t notice the absence of the balance weights on the preflight (they are visible on this type airplane). He also let a friend ride along.

About midfield on downwind the airplane accelerated to a speed that put it into the flutter envelope for an elevator installed without balance weights. There was just enough turbulence to excite flutter. The elevator promptly entered stop-to-stop, high cycle flutter that rendered the horizontal stabilizer largely ineffective, causing the nose to pitch down rapidly.

Knowing that control surface balance weights are no-go items and checking them on the preflight after replacement of a control surface would probably have prevented two deaths.

Firsthand Experience

Not long after that, three friends and I jumped into a Cherokee Arrow just out of annual and launched for EAA’s bash at Oshkosh. The left main wouldn’t retract completely. We returned and landed to discover that as part of the annual the gear door was removed. It connects via a piano hinge to the wing. The technician who reinstalled the door got the hinge points off by one and didn’t swing the gear again after reinstalling the doors.

All that happened to me was a two-hour departure delay. Not long afterward, a friend had almost the same thing happen in his Piper Saratoga SP following the annual. Except—he had the right main gear jam in that almost retracted position and got to make a two-wheels-extended landing.

A few years after that, I picked my Cessna Cardinal up from the shop after the annual, filed IFR to get back to home plate and launched. Cloud bases were at about 900 feet. At 500 feet I had a total electrical failure. I returned and landed. I learned that while moving wires to get at something behind the panel, a wire with eroded insulation ended up near part of the structure. Vibration on takeoff moved it the rest of the way, causing a short that turned everything dark.

The Rules

I’m a slow learner. It took that accident report, those two post-annual flight problems and some long talks with A&Ps and accident investigators to form some absolutely hard and fast rules for post-maintenance flights. Here they are:

- Day, VFR—no exceptions no matter how many days the flight has to be delayed.

- No passengers except perhaps a maintenance technician who worked on the airplane and is fully briefed on what will be happening on the flight and who will do what should there be an emergency. No matter how much someone else wants to ride along, it’s a strict no-go.

- They follow an especially cautious preflight that recognizes what has been worked on and the fact that other components of the airplane may have had to be moved or removed to get at the stuff that was the object of the maintenance. In other words, don’t just inspect the parts of the airplane that were worked on.

- The first 10-15 minutes of the flight is made within gliding distance of the airport. At a controlled field that means arranging with the tower to orbit above the traffic pattern and may take a little coordination.

I also think that it’s relevant to first-flight-out-of-the-shop risk analysis that the aircraft manufacturer for which I worked required that its test pilots wear a parachute on every first flight off the assembly line. The company’s quality assurance program was, in my opinion, first-rate and during the time I was there the worst that happened in those thousands of first flights was a gear hang up. Nevertheless, some smart people recognized that mistakes happen and put in an extra layer of protection for first flights.

Invasive Procedure

Years ago in a conversation with maintenance guru Mike Busch, he told me that he considers aircraft maintenance to be akin to surgery as the body is opened up. That struck a chord with me due to the number of knee surgeries I’d had and all of the doctors who had explained about the risk of “invasive procedures” before each one.

Yes, I’m harping on the risk, but so does the FAA, the outfit that certificates aviation maintenance technicians, as well as the NTSB, the outfit that has looked at too many first-flight-after-maintenance crashes. You can find guidance from the FAA and NTSB at https://tinyurl. com/4sswpjw7.

Statistically, the big-time post-maintenance accident creators are control surfaces and trim tabs. The NTSB preliminary report on the May 21, 2021, first flight after maintenance fatal crash of a pressurized Navajo indicated that the elevator trim tabs had been installed upside down and backward. More common is ailerons that have been hooked up backward. With saddening regularity that results in a roll into the ground within seconds after takeoff. Next on the FAA’s list is loose material or tools that jam controls.

Making Things Worse

Pilots have a way of being their own worst enemies when it comes to first flights after maintenance. The big one, according to A&Ps I spoke with, is picking up the airplane on Friday afternoon for a trip.

Admit it. You’ve done it. You rush out of the office to the airport with the family three hours later than the time you’d intended (and told the shop). Of course, in the real world of general aviation, cascading delays have also affected the shop as things have been going crazy with the usual Friday demand and assorted crises. Your favorite mechanic is just buttoning up the airplane following the annual.

It’s hot. You take the spouse and kids into what passes for a waiting area and tell them it’ll just be a few minutes. One of the kids wants to go to the beach right now. Your spouse is beyond frazzled after getting the house ready for the family to be gone and the kids packed and into the car—there is little holiday cheer in the air.

You’re under pressure to get going. You get a very quick brief from your A&P, including something about you probably shouldn’t have deferred the alternator issue, but it goes in one ear and out the other as you try to get a preflight going.

Logbooks?

You mentally kick yourself for yet again forgetting to bring the logbooks and convince your mechanic that the AD review can be put off until next week when you will absolutely bring in the logs, and he can give you the sticker for the annual then. You say that you don’t have time to wait around for that bit of paperwork. He reluctantly agrees to fill it out and have it ready when you come back.

The kids see you doing the preflight and the family comes charging out with all of the bags. You interrupt what you’re doing to get everything and everyone loaded.

Did I mention that it’s hot?

You fire up, taxi out and do an abbreviated runup.

You start the takeoff roll.

You can write the rest of this story.

What Are The Odds?

Most of the time things will be fine. But if you’ve been flying more than four or five years, you’ve had something go wrong on that first post-maintenance flight. What about that fuel selector that was turned off? Or the aileron cables hooked up backward? Or that the fuel tanks were almost completely drained so some leaks could be fixed? Or the air filter that was installed wrong and is blocking much of the airflow to the engine?

Let’s say everything goes just fine and you have a great flight to the resort. A few days later, when it’s time to come home, you look down at your iPad at the wrong time and run off a taxiway, down an embankment and into a fence. The airplane is seriously damaged, although no one is hurt. The FAA asks to see the airplane logbooks. One way or another it comes out that you flew the airplane before the logbook entry was made. Now you’re facing a certificate action.

Guidelines

Based on FAA publications, talks with a lot of A&Ps and hard-knock personal experience, here are my suggested guidelines for increasing the odds that things will go right when picking up and test flying your airplane after any maintenance work.

- Arrange to pick up the airplane anytime other than a Friday afternoon—and with enough time left so that you can get it back into the shop if you discover any sort of a problem on the test flight.

- Be by yourself under conditions where you will not be interrupted.

- Talk over the work done on the airplane and any things that are being deferred.

- Do a thorough preflight—the kind that you’d do on a checkride with the examiner watching (or after you see people leaning all over your airplane on the ramp at a fly-in breakfast). Don’t limit it to the stuff on the airplane checklist—check everything, especially anything that was the subject of the work or that had to be moved, removed or disconnected to do the work.

- If you get interrupted, start the preflight over.

- Check the stuff that you probably won’t need for the flight such as the pitot heat and external lighting. You’re at the shop. Now is the time to find out if something isn’t working and get it fixed.

- Throughout the time you are talking with the technician, preflighting or doing the test flight, recognize that any distraction or feeling that you are being hurried is a red flag. Slow down.

- Inside the cabin: Start with a smell check. Former airshow pilot and current A&P, AI and proprietor of Northern Air on the Boundary County Idaho Airport, Dave Parker, told me about getting a whiff of fuel after maintenance. He stopped everything and found that a fuel line had been disconnected as part of the work. It had not been properly reconnected and was leaking.

- Also inside the cabin before strapping in: Parker suggested making sure that all of the seatbelts are fastened—he has seen them jammed into seat stops and buckles laying right where a pilot’s hand may need to go in normal operations, such as beneath the manual gear retraction lever in older Mooneys.

- Control check. Make sure the controls—and trim tabs—move freely and in the correct direction. Dave Parker counseled us when doing a control check, to start by boxing the yoke or stick to get all the way into the corners of full travel and then take some time to move the controls through intermediate areas of travel.

Mindset

No matter how you run a checklist ordinarily, for this start-up and flight, approach things with a mindset that something is going to go wrong and you’re going to use the checklist meticulously so that you find that something before it gets ugly.

The accident reports show that distractions are killers—if you’re running a checklist and get distracted, start over. Yes, I know I said that previously. I wasn’t kidding.

Start-up should be by the book with you ready to shut things down right away if anything at all isn’t right. Oil pressure should be moving within seconds of ignition—if it’s not off the peg and on the way to a normal indication in 10 seconds, shut down and investigate.

Do everything on the checklist— don’t skip the autopilot ground check just because it wasn’t worked on. The work done may have messed up the autopilot.

Will the engine run smoothly at dead idle? Does the engine monitor indicate EGT on all of the cylinders and does each move appropriately during the mag check? Are the brakes working normally? Does the turn coordinator and its ball give proper indications as you taxi? Are all of the radios working correctly?

The Flight

I like the NASA launch approach for any takeoff, especially on the first flight after maintenance: The default for any decision is “No, until the airplane proves it can proceed.” For example: As I move the throttle to the full power position the question as to whether to start or continue the takeoff roll initially generates a “No” answer until the manifold pressure gauge and tach show that satisfactory power is being generated.

As pilot, you’re prepped to abort the takeoff roll if the next condition isn’t met—the airspeed needle comes alive. If it doesn’t, you abort the takeoff; if it does, you continue.

When it’s time to raise the nose and you pull back on the yoke, if the nose doesn’t come up it’s an immediate abort. If it does, continue.

If the airplane doesn’t lift off and start to climb and accelerate normally, abort the takeoff and land on the remaining runway.

Climb at VY for the first 1000 feet to get as much air under the airplane as quickly as possible while being alert for any indication that all is not well. Continue the climb to the initial altitude you’ve selected while maneuvering to stay within gliding distance of the airport.

Level off and follow the cruise checklist, setting power at the level you’ve planned (high if it’s an engine or cylinder break-in), leaning the mixture appropriately and setting trim and cowl flaps. Don’t stop looking outside for traffic, as you check all engine indications and check control responses and work your way through the checklist you’ve created to ensure all is well with the engine and airframe.

Then give yourself a little time to just fly the airplane at different speeds and power settings and check that CHTs stay at appropriate levels. Cycle the gear and flaps. Check the avionics again to make certain everything is working. Write down any squawks.

Bring It Back

If you run into anything wrong, bring the airplane back to the shop right then and let them start working to rectify the situation. For crying out loud—don’t fly the airplane home and then call the shop with a squawk list.

If there are problems, write down everything you can about each squawk, including altitude, power setting, indicated airspeed, outside air temperature and anything that you think will be relevant to troubleshooting and correcting the issue. Then land and head back to the shop with your list.

The chances are very good that the flight will be squawk free, especially because a careful preflight will have caught most of the potential problems. Now it’s time for the reward: Fly back to home plate with a nicely repaired airplane that you can land and put away or load the family for a lower stress flight to the beach.

Avionics Shakedowns Gone Wild

Given the deep teardown that’s often associated with avionics retrofits, the first few flights after a project can bring sizable risks. In a previous life as an avionics tech, I’ve experienced more dicey shakedown flights than I care to remember. This included an engine failure with an off-field landing, numerous electrical failures, smoke in the cabin and plenty of equipment failures the result of infant mortality. Whether your shop hands you the aircraft to test-fly the new systems by yourself or with them riding shotgun, approach the task with a healthy level of caution and start with a focused preflight inspection. Remember, avionics installs often include a lot of airframe teardown and in many cases, some engine and fuel system work, depending on the system interfacing.

The first thing to remember is that the project isn’t complete until it’s been fully flight tested to verify that everything works. Many STC installation manuals outline the items to check both on the ground and in flight. I’ve seen far too many owners schedule passenger-carrying trips on the first flight. Bad idea. I’ve also seen owners launch into low IMC on the first flight. Worse idea. It’s not a bad idea to limit the aircraft to VFR for the first few hours while you make close observations of the equipment and interface, while also getting comfortable with the new feature set and layout. I’ll never forget the hair-raising story from a turboprop owner who made the mistake of launching into low IMC with a new EFIS/autopilot interface. He was seconds away from losing control of the aircraft because the autopilot was doing something he didn’t expect it to do (it turned to the opposite heading than what was bugged) while he was busy doing other things. If you don’t know the new system cold—and that includes potential failure modes—take the time to get some training. We covered avionics training in the June 2021 issue of Aviation Consumer and found there are plenty of good options.

On the preflight inspection, look carefully for missing and loose fasteners on inspection plates, cowlings and interior components. I remember the cabin headliner falling onto our heads during the initial climbout in a small twin and it was a huge and unexpected distraction. Is there enough fuel in the aircraft? Just because you dropped it off with half tanks doesn’t mean it still has the same amount. If there was a new engine monitoring system installed, it’s likely that the shop had to offload the fuel as part of the fuel quantity interface. Take a good fuel sample and look carefully for sediment and water, and visually verify the amount in the tanks with what the display is showing. Speaking of fuel, if there’s any hint of fuel odor in the cabin it’s grounds for returning immediately to the airport or taxiing back to the ramp. On one particular flyoff in a Beech Baron I got a strong whiff of fuel while on a GPS approach and soon spotted it dripping from under the panel. Turns out a tech forgot to tighten the fittings on the fuel flow gauge and raw fuel was dripping from the casing—and over wiring bundles. If you get into the aircraft and smell fuel, say something.

Perhaps the biggest potential for disaster are newly installed or repaired autopilot systems. There are good reasons why retrofit systems have flight manual supplements, and they outline regular, emergency and preflight procedures. Most if not all of these supplements prescribe doing a preflight check either on the first flight of the day or even before every flight. For starters, you are looking for proper autopilot disconnection—via the disconnect switch and the system circuit breakers. And when the system is engaged, can you overpower the servos? You should be able to slip the clutch on the servos and have full control of the flight controls. Does the pitch trim run in the proper direction—both with the command switch and when the autopilot’s altitude hold is engaged? It’s easy to miswire, and trim that runs backward can be a killer—as is runaway trim. I’ll never forget the takeoff roll in a big Cessna twin where the autopilot ran the automatic pitch trim to the full nose-down position. Both I and the pilot flying missed it (actually, it was running during the takeoff roll), and you can image the control force required to rotate a Cessna 421 with full downward trim. It was a close call that like most failures could have been avoided by a more thorough preflight inspection. – Larry Anglisano

Rick Durden is an aviation attorney, CFII, holds an ATP with type ratings in the Douglas DC-3 and Cessna Citation, and is the author of The Thinking Pilot’s Flight Manual or, How to Survive Flying Little Airplanes and Have a Ball Doing It, Vols. 1 and 2.

This article originally appeared in the August 2021 issue of Aviation Consumer magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to Aviation Consumer!