Skydiving Save: Wearing the Hero Mantle

I suspect AFF instructor Sheldon McFarlane was as uncomfortable being called a hero as most of us would be in that situation. I’d call him a skilled professional doing his job.

I suppose it has ever been thus, but these days, we're all appreciative and always looking for someone to wear the mantle of hero. That more than anything explains why that video of the incapacitated skydiver being saved by his instructor went viral over the weekend. I saw it on NBC news Sunday night as a 10-second short, but by Monday morning, it was everywhere and it got more second-day coverage Monday evening.

To my surprise, we even ran it. Russ Niles and the AVweb newsteam make up the daily feed independent of my input, although I see everything before it's published. When he sent the story my way in our e-mail loop, he amended it with "holy crap!"

I suspect my skydiving friends would be amused by that reaction, not because it isn't warranted, but because as is always the case, the view from inside any activity highlighted in the mass media is more nuanced. My reaction to the clip was that it was an exceptional example of a hardworking AFF (accelerated free fall) instructor doing his job. By that standard, anyone doing competent work in any field is a hero. Or none of us are. That sounded like the reaction of the instructor, Sheldon McFarlane, when someone stuck a camera in his face and declared him the real deal. He looked a bit pained, actually.

AFF instructors are the unsung backbone of skydiving. (Notice I didn't say heroes.) They bring new people into the sport—which is in fact, growing—at the expense of fairly rigorous physical effort and no small amount of nerve. Basically, they're hurling people out of airplanes and teaching—or forcing them—to fall stable and deploy parachutes, an unnatural act for which our DNA in no way prepares us. For new skydivers, the overwhelming challenge isn't so much the physicality as it is learning to think, analyze and act with a quart of adrenaline surging through the veins. It's an OODA loop run amuck. In describing the inability to function in freefall, even for experienced jumpers, one of the funnier euphemisms is "fire in the helmet."

These days, we have vertical wind tunnels to help with the stability part, but AFF instructors still have to confront surprises when stepping off the airplane. I've seen more than one come back with bruises and bloodied parts from getting whacked by a spinning or tumbling student. It's not the sort of thing a high school English teacher or even a flight instructor might expect to encounter. A tip of the helmet to them all; AFF instructor is a rating I never wanted to pursue.

Now for the nuance part. The initial clip left viewers with the impression that had the instructor not been there, the student, Christopher Jones, was seconds from becoming a bug splat on the Australian countryside. Not exactly. In fact, not at all. These days, almost all skydivers are equipped with something called an automatic activation device. We've had these things for decades, but the advent of digital electronics have made them sophisticated and reliable.

Using baro sensing, AADs figure out speed and altitude and, if their logic determines that the jumper hasn't deployed something by a certain altitude, a little cutter squib slices through the reserve parachute closing loop and deploys it. Jones was equipped with an AAD, as all students and the vast majority of experienced jumpers are. It would have deployed his reserve at about 1000 feet, which is plenty of time for a canopy to inflate.

But here's the tricky part and, if you insist on considering McFarlane a hero, the real reason for it. And it doesn't have much to do with the likelihood of an AAD failure. Landing unconscious under a reserve parachute is no picnic. Even with the brakes stowed, as they would be, it has forward motion of maybe 10 mph. If the incapacitated jumper landed downwind, add the windspeed to that. It could be a hard face plant at three times your fastest running speed. That might be okay in a nice grassy field, but it could be fatal when obstructions like houses, power poles or vehicles intervene.

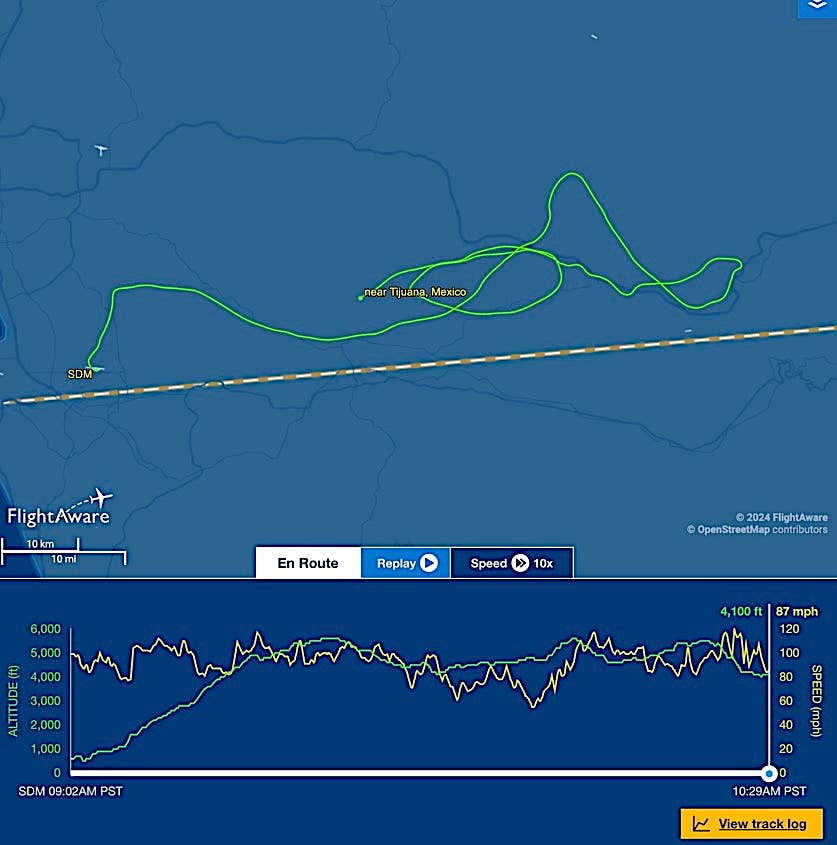

McFarlane's decision to get his student's reserve out high as possible—at about 4000 feet—gave him more time to recover consciousness while under canopy and land himself safely. And that's exactly what happened. The actual deployment altitude was probably close to where the student should have deployed his main anyway.I don't know if McFarlane weighed that or not, but I can't think of any arguments against getting the reserve out sooner rather than later, unless perhaps a drift over open water is a worry. I think the doctrine is to just get the reserve out. But whether he did or didn't, McFarlane's actions were just another example of a professional in a high-risk sport doing a job he was trained and expected to do. In other words, a hero of the everyday, just as you probably are, too.

The real holy crap moment for me was when I saw this still frame from the video. In deploying any parachute, you really want a stable, belly-to-earth body position so the whole shebang comes off your back, the lines unstow and the canopy inflates unhindered. This is especially true of a reserve because if it fails, you're fresh out of parachutes. But Jones was on his back, so, as the photo shows, the deployment bag whizzes past his foot and the lines are pretty close to his legs and feet. It doesn't take much to loop a foot or leg into that process and then you've got a real mess. That's probably another argument for higher deployment, but it still gives me the willies.

When I began skydiving, it was traditional to present your rigger with a bottle of whiskey after you deployed a reserve he or she packed for you. I think it's only occasionally observed now. Hero or not, McFarlane (and the rigger) deserve an entire case.

Join the conversation.

Read others' comments andpost your own.