Hear Back, Read Back

There’s an amusing quip from award‑winning author Robert McCloskey that says, “I know that you believe you understand what you think I said, but I’m not sure you realize that…

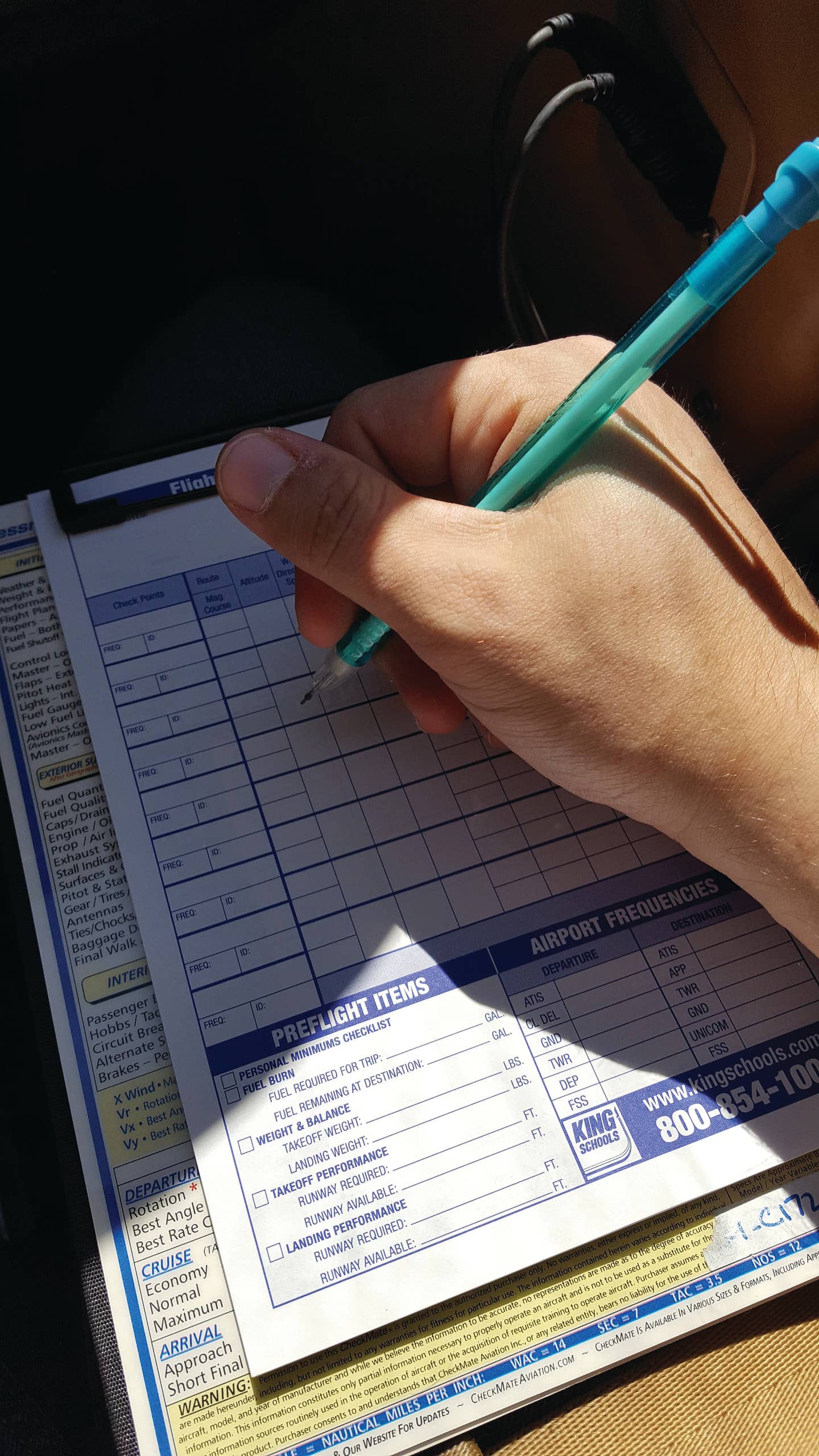

Correctly reading back your clearance begins with careful and legible notes. Image: Elim Hawkins

There’s an amusing quip from award‑winning author Robert McCloskey that says, “I know that you believe you understand what you think I said, but I’m not sure you realize that what you heard is not what I meant.” This double speak serves to illustrate the importance of clear communication. There are few places in human endeavors where that’s as critical as in pilot‑ATC communications.

Full Circle Comm

We all do it often—we’re on the phone and want to write down important information like an address, phone number, etc. We both want to get it right, so the person hearing the information repeats it for confirmation. A simple miscommunication and you are headed to a party in the wrong part of town.

Hear back, read back is exactly what it says. We hear something and repeat it to make sure it’s right, and the person who said it carefully listens to what you’ve repeated. Outside of aviation, skipping the confirmation step and ultimately getting something wrong usually—but not always—has minor consequences. But in the air, communication errors can easily cause big problems.

One of the first things a student pilot learns is to listen carefully to an instruction and read it back. What exactly did you hear? How do you apply it? Does it require a readback? What do the books say, and what does ATC expect?

Let’s start out with a few simple examples and work our way up. One of the most‑used examples is, “Tower, Cessna 12345, ready for departure, Runway 14L.” “Cessna 12345, Tower, hold short Runway 14L.” The caution below appears on many charts, but have you really assimilated what it’s telling you? It’s simple. Essentially, if the controller says the word “runway” you should read back the explicit instruction: “Cessna 12345, holding short Runway 14L.” This is the proper way to respond.

Pilots who don’t reply explicitly like to play what I call the “hold short” game. Controllers are required to hear the call sign, the words “hold(ing) short,” and the precise runway name, otherwise, we go back and forth until you say it. Note that a common variation, “Cessna 12345 holding short of the left,” is insufficient because the runway name isn’t explicit.

If you’re told to read back hold‑short instructions, it is because you may not have read back the entire clearance or maybe someone stepped on the frequency and Tower did not hear it. It only becomes a big deal when we are talking to each other for a while without the required call. Fun fact: the main reason this rule was added as a requirement and put on the taxi diagrams was due to the increase in runway incursions back in the day. Overall incursions have gone down since then, but we’re always striving to improve safety.

Now, let’s briefly get into something a little more complicated, a PTAC. For those unfamiliar, PTAC is an acronym that controllers use when setting someone up for an instrument approach procedure. It stands for Position Turn Altitude Clearance. It normally goes something like, “Cessna 12345, five miles from DAFIX. Turn left heading 180. Maintain 2500 until established on the localizer. Cleared ILS Runway 21 approach.” Depending on location, you might even get a “Contact Tower when established” or for an uncontrolled field, “when able cancel IFR with me or call flight service.” Yes, there’s a lot going on there.

If that’s too much for you to digest in one transmission, you can always ask ATC to “Say again,” or “Can you say that a little slower?” The pilot in this situation is normally expected to read back something along the lines of “Cessna 12345, left heading 180, 2500 until established, cleared ILS 21.” It isn’t verbatim, but it has the required info, and it satisfies the controller’s requirements. The nice thing about all this is if you don’t get all of it right, maybe just read back the incorrect heading, controllers can do a simple fix with, “Cessna 12345, heading 180.”

Also, in this clearance, you don’t have to readback your position (five miles from DAFIX). That is ATCs way of saying who they are looking at. Being situationally aware, pilots should generally know where they are, thus hearing something that doesn’t describe you but with your callsign, you can simply reply, “Approach, we are 10 miles from DAFIX, please confirm.” It happens, but not often. I hope it’s not getting too tiring, but I always like to emphasize—if you don’t know or aren’t sure, just ask for a clarification. Moving right along…

The Books Say…

There is a lot of contradictory information and beliefs about hear back, read back. Some pilots read it all back and a select few only say, “Wilco.” They have the words “non‑regulatory” in their heads when it comes to most things in the AIM. Interestingly enough, not following what is recommended in the regs or AIM has been cited in many incidents and accidents and certificate actions, so they can still pin it on you. Searching all publications where hear back, read back is cited, one could see some grey areas. For this, there are three sources I look into. The first main ones are 2‑4‑3 in the 7110.65 controllers’ rule book, 4‑4‑7 in the AIM and §91.123 in the regs.

Starting with ATCs 7110.65, 2‑4‑3 requires us to “Ensure pilots acknowledge all Air Traffic Clearances and ATC instructions. When a pilot reads back an ATC clearance or instruction…a. Ensure that items read back are correct, b. Ensure the read back of hold short instructions, whether a part of taxi instructions or a LAHSO [Land and hold short] clearance, c. Ensure pilots use call signs and/or registration number in any read back acknowledging an ATC clearance or instruction.” Okay, that’s what the controller must do.

The need to make sure the read back is correct is obvious, but workload often seduces us to move on while you’re reading something back. Making sure hold short instructions coincide with what we talked about earlier is straightforward.

Of course, making sure pilots use the correct call sign is simple common sense. A pilot looking for a turn might take someone else’s clearance by mis‑ take; thus, we have to correct and re‑issue to the correct pilot. For controllers, the 7110.65 is considered regulatory. As Yoda said, “Do or do not. There is no try.” We either satisfy the above, or we need to pester you until we do.

AIM 4‑4‑7 is titled, “Pilot Responsibility upon Clearance Issuance.” In effect, it’s about doing what you are supposed to do upon being told to do it. Pilots are required to “Record ATC Clearances.” And it makes no distinction between being on the ground or in the air, so, yeah, full AIM compliance means writing down the various altitudes and headings you’re given.

Further, “Pilots of airborne aircraft should read back those parts of ATC clearances and instructions containing altitude assignments, vectors, or runway assignments as a means of mutual verification.” It also says to “read back in the same sequence as they are given in the clearance or instruction.” This makes it easier for controllers, since it’s the order in which we’re thinking.

You might have noticed that the requirement to read back a clearance only is stated for aircraft in the air. We’ve talked about this before, but it’s true that you’re not required to read back that initial clearance you got from Clearance Delivery. Yeah, but…

In the regs, §91.123 essentially says we’ve got to do what ATC tells us to do except in certain edge cases like an emergency. No big deal; we do what we’re told, right? We just noted that there’s no explicit requirement for a ground‑based readback (unless it requires runway instructions as covered at the beginning). This can be a grey area, and here’s my personal view on it. No, the readback isn’t required—until ATC asks you to read it back. Then not doing so could be interpreted as a violation of §91.123 to do what ATC says.

Keep in mind, that we do our best to keep things running smoothly and safely. One way we do that is to ask for a readback of important instructions (like an initial clearance on the ground) if we don’t get one. I am even authorized to deny a departure until I get a full and accurate readback. Yes, that can sometimes take a while, but it ensures you don’t turn the wrong way at a VOR and have a near miss.

I’ve only had to hold one pilot to get a readback. It was about a year ago, and he appeared to have a little get‑there‑itis. So, I responded with a calm “There is no hurry, Sir. Advise ready to read back,” to slow him just a little. We all know that going out of our way to make something happen (or not) for a matter of safety is a daily occurrence. Why do you think we keep saying, “Caution Wake Turbulence” all the time?

Psychological Standpoint

The hazardous attitudes of flying can be applied to the ATC side of things as well. If we don’t get a proper readback, we’ll ask for it until we get it. This, in turn becomes a stressor that neither of us needs. For a variety of reasons, we all get pressured and in a hurry at times. Pilots might be feeling some external pressures to hurry things along and might breeze through a readback, missing something. But, to keep a busy time from getting worse, controllers still find themselves wishing for a readback as efficient as the instruction was delivered.

Quick tip; Remove “Hurry up!” from your thinking, and this includes working with ATC. Not too long ago, I was working ground and clearance delivery when I had about eight pilots call me within a minute. Five wanted to taxi, three wanted their clearance. Once I had the ground traffic moving, I started to rattle off clearances like there was no tomorrow. Two pilots read their stuff back efficiently, but the third said to me, “Wow! Have you not had your coffee this morning?” In the moment I was angered, but that verbal slap in the face put me in my place. Looking back, I didn’t need to be in such a hurry.

What to Fly Away With...

Despite “Hear back, read back” being one of the first skills pilots develop, the ability to efficiently and accurately read back an instruction can get stale over time, just like your stick and rudder skills do. Despite the vagueness and contradictions in the official guidance, we should all be ready to go above and beyond (quite literally) to ensure safety. I’ll close this treatise by adding one of my biggest pet peeves in radio communication with ATC: You should always (!) put your call sign somewhere in each and every transmission. Help us help you.

Cleared the Wrong Way

A few years ago, I was working on a relatively slow day when a TBM called up looking for his clearance. After pulling it out of the system, the trainee I was watching went to read it to him. “Cleared to APA airport via radar vectors, XXX departure, FIX, VOR, direct. Maintain 3000; expect flight level 210 in 10 minutes. Departure frequency is 123.4. squawk 1234.” The pilot read back the clearance verbatim, and that was it.

He taxied out, we got a release, and cleared him for takeoff. About an hour and a half later we get a call from Denver Center asking about this clearance. We pulled the strip, looked at it, and read it to him. At first, I didn’t realize what the trainee had done, nor did I spot it. The Center controller caught it quick, “You cleared him to that VOR? That’s not where he was supposed to go, especially at that altitude. He came too close to an airliner.”

With the help of Skyvector.com, I looked up the route and the VOR that the trainee had said compared to what the pilot should have had. He was about 100 miles off his route, and the main cause was that the trainee’s handwriting over the route made the VOR look like another identifier. So instead of ABC, it looked like ABO. Ultimately it was my fault for not double checking, but this trainee was far enough along that I wasn’t standing over his shoulder.

We had to file a report about the whole thing and we all learned a good lesson—especially me. The pilot, a friend of mine who came back the following day, also got a talking to. They asked him after he read the route back and checked it how he missed it by 100 miles. We all got slaps on the wrist for that one.

I’d missed it; the trainee wrote it incorrectly and therefore misspoke; and the pilot didn’t verify. It also didn’t help that the VOR in question was in the same direction of Denver compared to where we were. To learn from our mistake, my trainee and I did some refresher training on reading clearances and which VORs are which. As a freshly minted instrument pilot, whenever I flew after that, I would carefully read my clearance back, and then double check it with my GPS or ForeFlight.

ATC has helped Elim Hawkins get to the point of being able to remember a short paragraph and read it back. It is very useful when his wife asks him to bring home milk…and bread… and…

For more great content like this, subscribe to IFR!