Devotion: Made Like They Used to Make Them

As fall turns to winter, the honest and inspiring story of Jesse Brown is a welcome antidote to glitzier films.

If there’s a single word to describe the recently released film Devotion, it would be restrained. Or perhaps understated. The writers and director resisted the urge to tart up the production with the over-the-top CGI pyrotechnics that I thought ruined Red Tails and although racial strife has a role in the story, the director admirably resisted making it the star. The viewer will get the point without being hammered senseless by repeated displays of racial injustice. In that sense, and given that director JD Dillard is himself black, it’s possible that this film represents a departure in how Hollywood, or at least one small segment of it, depicts the complicated history of race in these United States. Or maybe I should exercise restraint myself and just call it a good flying movie. It certainly is that.

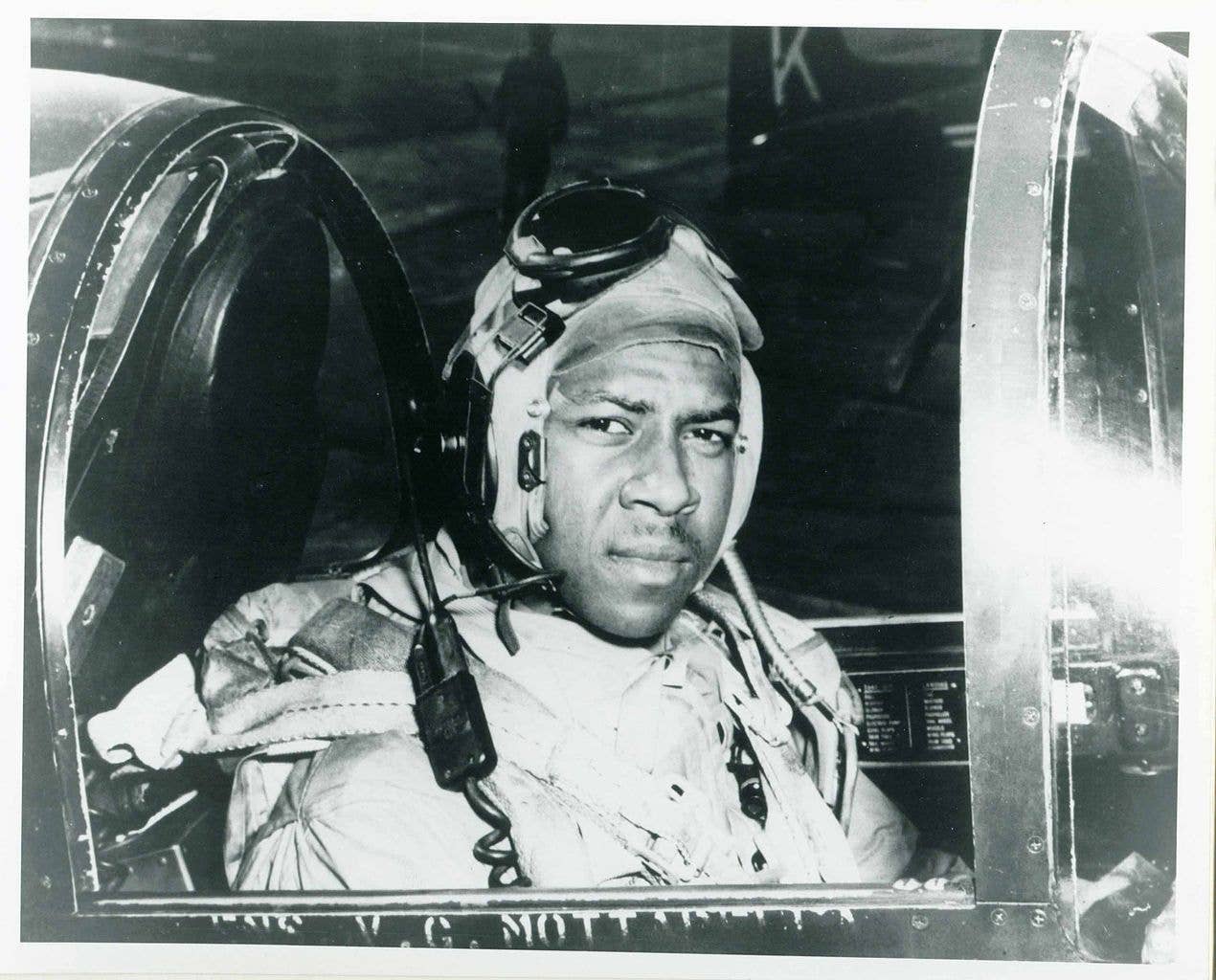

Anyone with even a passing knowledge of Korean war airpower will know the story. Ensign Jesse Brown was the Navy’s first black pilot, having earned his wings in October 1948, just three months after President Harry Truman ordered the military to integrate. Not that this had much to do with his story, nor is it mentioned in the film since it was well into the 1950s before all the services haphazardly complied with Truman’s order. By then, Brown had died in Korea, having been downed by ground fire near the Chosin Reservoir in December 1950. The film’s title derives from what happened after Brown crash-landed his F4U Corsair on a snowy hillside.

Realizing he was trapped in the burning wreckage and in an act of stunning selflessness, Brown’s section leader, Lt. Thomas Hudner, crash-landed his own Corsair in an effort to extract Brown. Assisted by rescue helicopter pilot Charles Ward, he was unsuccessful. Hudner was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his bravery. So how to tell the story?

In his 2017 book, Devotion: An Epic Story of Heroism, Friendship and Sacrifice, author Adam Makos related the tale in detail. I haven’t read the book so I don’t know how well the film adheres to it. Not that it matters, because the overall arc is clear. To set the story in motion, Hudner—played by Glen Powell—meets Jonathan Majors’ Jesse Brown at what was then Naval Air Station Quonset Point, in Rhode Island. Powell, by the way, redeems himself from the cartoonishly egotistical pilot, Hangman, he played in Top Gun Maverick. (Yeah, that guy … erase him from your memory.) The two begin their bonding in a gorgeous two-ship training flight in a pair of F8F Bearcats, leftovers from the Pacific carrier war.

Director Dillard pledged to have as many scenes as possible shot “in camera,” as they say, rather than cobbled together with CGI. But CGI is so convincing now you sometimes can’t distinguish between computer graphics and real practical shots. The Bearcat scenes were real shots in trail of the CineJet, a camera-equipped L-39. A Phenom 300 was also used. In-cockpit Bearcat shots, which are equally convincing, were shot as they were in Top Gun Maverick, with the actor in the back of a two-seater. Some CGI is used in some scenes, but it’s stitched in seamlessly.

I’m not sure how many F4Us were used, but spy reports said at least three, plus the Mig used in the air-to-air combat clip. CGI was used to add more aircraft to some scenes and this is where the lure of Hollywood proved irresistible. If you can add a section of four, why not 12? Or 20? So they did. The same thing happened in the original Korean war epic, The Bridges at Toko-Ri. The Navy cooperated fully on that film and noted to the director that it didn’t actually do dive bombing attacks in large formations. The director said they had shot scenes that way since Howard Hughes’ Hell’s Angels in 1930. Evidently, they still do.

But it’s a minor ding. The glitzy effects don’t overrun Devotion’s storyline and in most of it, they enhance it. For example, for all the great practical footage of jet traps used in Toko-Ri, one thing not evident was that those guys were landing on a straight-deck carrier, often into a barrier. In Devotion, the Corsair traps are all CGI and thus the camera can be behind the airplane. You can see that it’s landing into a barrier with aircraft spotted forward. In those days, a bolter was an iffy thing and a lot of them ended up in the barrier or upended in parked aircraft.

The film also alludes to the difficulty of landing a Corsair on a carrier. It had two terrifying shortcomings. One was the long nose which, in the landing configuration, obscured the deck and the Landing Signal Officer. Second, the Corsair had an asymmetrical stall that caused it to roll left sharply. This was aggravated if the pilot applied power rapidly, causing an unrecoverable torque roll. One short segment in the film depicts this, as the squadron’s first casualty.

The young pilots are thus put on notice for what they are about to face. The Corsair’s nasty trick was later fixed with a stall strip and, thanks to the Brits, a tight curving approach was developed so the pilot could have eyes on the carrier until just before touchdown.

Director Dillard was advised on the film by his father, Bruce, a member of the Blue Angels in the early 1990s. According to the son, that led to one of most affecting if quiet scenes in Devotion. As Brown is about to deploy, there’s an emotional conversation with his wife Daisy over what the long separation and the dangers of combat will mean. Too many people who have no military connection are ignorant of the price paid by those who do. Dillard was right to include this scene.

The script is less adept at developing the relationship between Brown and Hudner that justifies the title, even though I think the title is justified. Majors’ Brown is distant and somewhat reserved—as the real man might have been—but eventually opens up enough to Hudner to provide a glimpse of his difficulties in negotiating an insular Navy flight culture to earn his gold wings. It almost had to be pried out of him but enough of it emerges to give the viewer a sense of the bigotry and harassment he endured in trying to break into what had been, might as well admit it, a white man’s club. He stood on the shoulders of the Tuskegee project to succeed, but succeed he did. This is ground also well trod in Men of Honor, the 2000 story of black Navy diver Carl Brashear.

The onscreen Brown and Hudner develop a friendship, but you don’t get the sense it was a close one. More of mutual professional respect. The final scene at the snowy crash site is acted with impressive grace, when Hudner and Brown communicate the hopelessness of his situation with unspoken emotional facial expressions. It’s at that point that I thought it was less friendship that justified the title than devotion to the determination that no warrior leaves a fallen warrior behind. This was driven home with unmistakable clarity by a strong supporting performance from Thomas Sadoski, as the war-wizened squadron XO, Dick Cevoli.

But Hudner had no other choice than to leave his wingman. In later life, he made efforts with North Korea to repatriate Brown’s remains, but it wasn’t to be. To this day, Brown’s burial site is listed as the Chosin Reservoir, halfway between the Chinese border and the DMZ.

It's worth noting that the Chosin Reservoir campaign took place 72 years ago beginning today, November 27th, 1950. It ended on December 13th, after a fighting withdrawal to Hungnam, where Marines and Army were evacuated by sea. Ensign Jesse Brown was providing air support to cover that withdrawal.

Ten years ago—yes, it has been that long—George Lucas funded the $58 million cost of Red Tails himself because he couldn’t interest the film industry in a production with an all-black cast. Furthermore, the industry couldn’t see a foreign market for the film. The film earned $50 million. Would it be different today? I give you Black Panther, which has earned $1.3 billion on an investment of $200 million. Wakenda Forever, the sequel, is on the same track. All black casts but not about World War II.

This makes me wonder how Devotion will perform because as good as it is, I don’t understand who it’s for. Sure, it will appeal to Boomers, people with an interest in history or war films in general, but that’s a tiny and shrinking audience slice. I wonder what younger people will think of Devotion because it’s ancient history and they may be weary of stories about racial strife that they may consider a past not worth remembering. In the theater where it played in Sarasota, there were about a dozen people in a venue for 300.

I hope I’m wrong about this. This is a story well worth telling and Devotion does it superbly.

Following his service in Korea, Thomas Hudner served in a number of aviation command assignments, including a non-flying stint in Vietnam. He retired from the Navy as a Captain in 1973. He lived to see an Arleigh Burke-class destroyer named in his honor. The USS Thomas Hudner was launched on April 1, 2017. Thomas Hudner died on Nov. 13, 2017. He was 93.