Flying Freight In The Corona Crisis

Coronavirus lockdowns have impacted aviation in unimaginable ways, including freight carriers. They’re busy, but this is not normal.

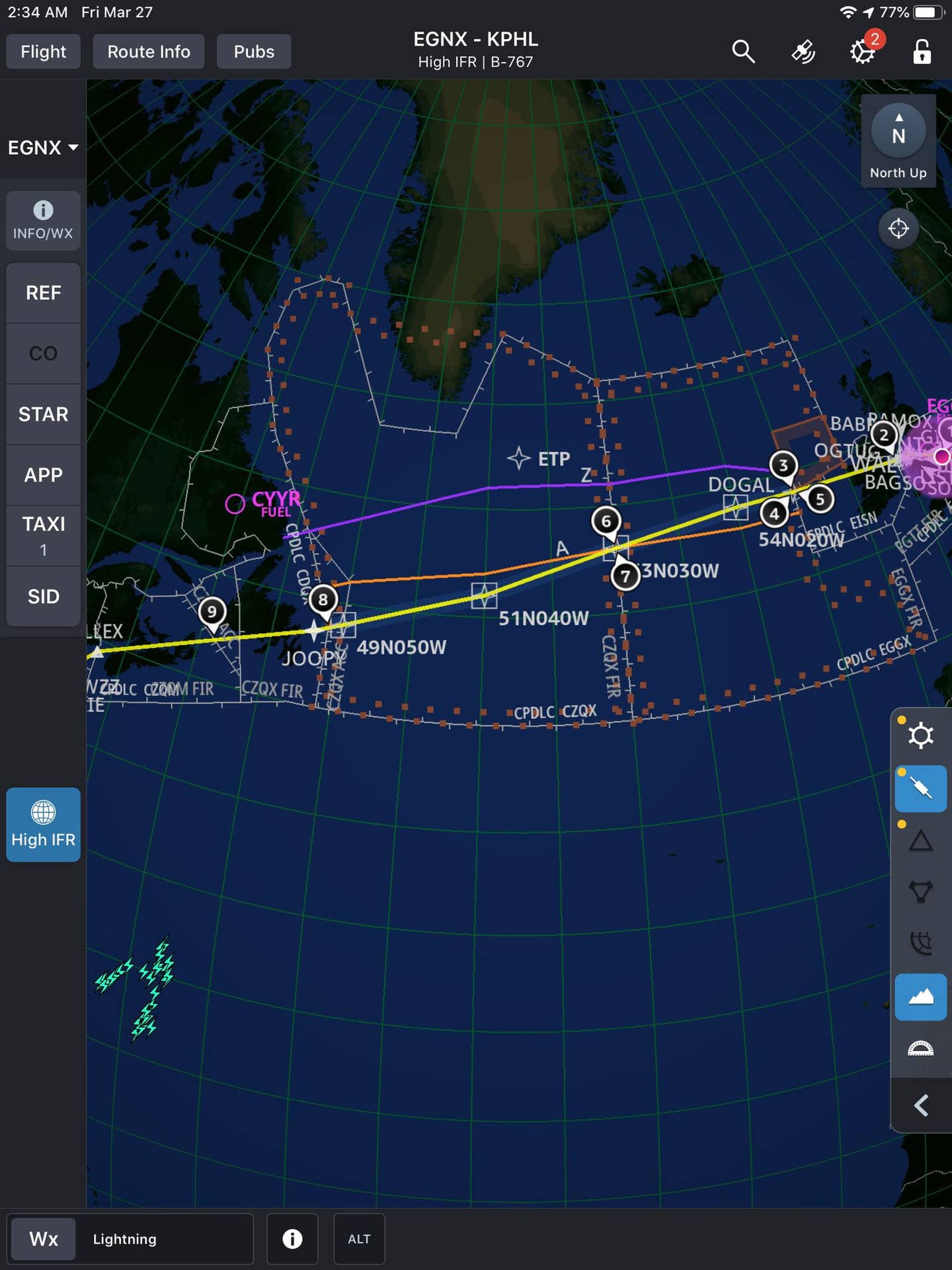

Two North Atlantic Tracks where normally there might be as many as eight.

I’ve never really considered myself to be an essential person. Of course, in the larger sense of community, we’re all essential. But outside of my immediate family and my pets, no one has ever considered me essential. That was until a few weeks ago when the U.S. government did. I have been working for a large overnight package/freight carrier for the past 30 years and at that moment, I received a field promotion from Freight Dog to Essential Personnel in the war on the COVID-19 virus.

I’d been at home or traveling on vacation for much of the crisis’ early days but last week it was my turn to go to work. As you can imagine, I had my own set of worries about traveling to Europe in the midst of a pandemic and these concerns were reinforced when I saw pictures that my co-workers were sending from Germany. The town that has for some time served as my home away from home, where I had so many memorable evenings and some that people tell me were memorable but that for some strange reason I don’t remember, was on lockdown. This was weeks before anyplace here had been, and if you know anything about Germans, they take the rules very seriously. The streets were empty and reports were that everything was closed.

The first segment of my trip was a deadhead seat on a passenger airline flight that would get me into position. We can make our own travel arrangements for this so I chose to take a train from my home in Philadelphia to Newark airport where I had a business-class ticket on United Airlines to Frankfurt. I’d been hanging around the house for a while by that point, maybe a bit removed from the world outside of our suburban village, and I was shocked to be dropped off at the main Philadelphia Amtrak station and to see nothing but desolation. I was a little early and there were seats, but was it safe to sit in them? There were two other people nearby but they had masks. Should I talk to them? I decided standing was probably my safest course and that I should maintain my distance. What our society used to consider a negative, being socially awkward, has turned into a positive with a shiny new name: social distancing. I had an assigned seat on the train but it was so empty that I could have spent the next hour trying out every seat in every car. I didn’t.

At Newark, the ticket kiosk flagged me and wouldn’t issue a ticket. A day or so earlier, Germany had locked down its borders and no one without a German passport was allowed in. I explained my newly bestowed essential status and the human agent summoned her supervisor. I got a printed boarding pass. You could have easily rolled a bowling ball down the concourse and not hit a soul. All of the shops, restaurants, bars and premium lounges were closed. I found one of United’s Red-Carpet lounges open and spent two hours luxuriating with kid-sized packages of pretzels, carrots and cookies. Wine was free, but I was warned by other pilots that going through immigration at the other end might go smoother if I wore my uniform, so I stuck to diet Coke.

“Boarding group One may now board the plane.” The agent stopped me. Can’t board with a U.S. passport. I was directed to the service desk, confident they would bow to His Essentialness and let me pass. I showed my pilot credentials and work ID, but she wasn’t buying it. As this went on, I could hear, “group 2 may now board,” group 3 and so on. Group 7. Would I miss my first trip in 30 years?

Finally, with everyone else on board, the agent asked me if I had a printed copy of my schedule to prove what I was saying. I did not and finally tried one last appeal to sanity.

“What can I possibly show you that I couldn’t have made up at home that would prove to you that I am going to Germany to operate air service between European cities? Is this something people regularly come to you with as a bluff to get on airplanes while holding an expensive ticket?” I saw gears turning in her mind and she threw her arms up and let me get on the plane. If there are any problems, they’ll take care of them at the other end.

As it turned out, our crews all over the U.S. were having the same issues as they tried to get into position. The first officer that I was paired with was coming from Dallas and his Dallas-to-Frankfurt flights kept getting canceled. Finally, American loaded him on a flight from Dallas to London where he would connect with a British Airways flight for the final leg to Frankfurt. No amount of talk could convince the British Airways agent of his essentialness and they refused to board him. He found his way across town and rode in on one of our company flights from Stansted airport. Everyone eventually made it over.

A nice flight and I slept through most of it. This was my first exposure to a grounded fleet. Lufthansa had grounded a large percentage of their fleet and most of them seemed to be out my window, lined up on every stretch of pavement at FRA. One taxiway seemed to be dedicated to the giant Airbus A380—all 14 of them wingtip to wingtip on the taxiway.

No real problem at the other end. The immigration officer was just puzzled about what I was doing there.

“So, you are flying a plane tonight?”

“Yes.”

“United back to the U.S?”

“No, around Europe.”

“Cargo?”

Our company likes to refer to our loads as “packages,” but this was no time for a grammar lesson. “Yes.”

“OK.” One more stamp in my loaded passport and I was in.

A quick stop in the airport supermarket for some supplies. Yes, the Frankfurt airport has a supermarket. I knew that there was a potential for food problems and I figured I'd better get some while I can. I loaded up on ramen, dried sausages and anything else that could provide sustenance as well as some chocolate for the family back home. There is a stereotype that commercial pilots are pampered and everything is taken care of for us before we waltz down a red carpet to our aircraft. I chuckled about the disparity between that and the reality of me stocking up on Cup of Noodles and German Slim Jims.

One more deserted train and I was there. The pictures that I had seen did not lie. The Germans can teach us a thing or two about quarantines. Looking both ways before crossing a street was not necessary. There were no cars. Once in a while you would reach an intersection with a traffic light and see a few other pedestrians. I laughed at how even with no cars as far as the eyes could see, they were obeying the German tradition of staying put until the light changed from Don’t Walk to Walk. It reminded me of Blazing Saddles where Slim Pickens sent one of his henchmen back to town for “a boatload of nickels” when they encountered a fake toll booth in the middle of the desert. In Germany, the rules are the rules.

I got to our hotel, which was closed except for our flight crews. At a given time there are about 80 or so of us there, and someone had convinced them to keep their doors open for us. That’s a scene that seems to be happening more and more around the world. I get alerts daily about hotel changes as hotels close up and consolidate their guests.

There’s a restaurant in town that our guys tend to congregate at in better times and the owner had decided to stay open for us during very limited hours. You could walk the few blocks to her place but only in a group no larger than two people. A larger group ran the risk of incurring a 500 Euro fine. Takeout meal in hand you go back to the hotel and eat in your room. The first few people can eat in our crew lounge, but they are afraid if there are more than 5 of us in there at any time the authorities will close the hotel.

Hotel pickup at 3 a.m. for a flight to Warsaw. Cleanliness and disinfection of the airplanes had been an ongoing concern. Our cockpits get a deep clean once in a while, but I don’t think anyone really knows when as evidenced by some of the flotsam I have found between the rudder pedals. Typically, food, and typically round. Think oranges and hardboiled eggs. During these times, we are given assurances that the planes will be kept cleaner. Armed with our supplied N95 masks and bottles of hand sanitizer, we headed out to the airplane, a Boeing 767. They had run out of the “good” sanitizer and were issuing little bottles of a homemade solution of watered-down bleach. I’d have to say that stuff may kill germs in an emergency, but it is not for regular use. Madge, the Palmolive lady, would not approve. After using that stuff my hands looked reptilian.

There was a notice on the captain’s control wheel that the airplane had been cleaned and disinfected with a name and a time stamp, but also the notice that they had not touched anything forward of the center pedestal which is the area we live in, or any of the flight instruments. On the center pedestal was a bottle of Clorox wipes inscribed with the tail number of that plane to make sure it didn’t grow feet and walk off. I have to question the efficacy of this. It’s very hard to get all of the nooks and crannies on an instrument or switch panel. An aerosol or an ultraviolet light treatment would seem better, but what’s the saying, you go to war with the army you have, not the army you want.

Headwinds added a lot of time to our flight but we got to Poland just as the sun was coming up. Not much traffic on the radio but at the hours we fly over there, that’s the norm. Landing at Chopin airport revealed the fleet of the Polish national airline, LOT, taking up most of the ramp space with their 98 aircraft. We were met in the cockpit by two masked Polish soldiers who had some health papers for us to fill out before they took our temperatures.

The normal early morning rush hour did not materialize and we were dropped off at a largely abandoned high rise containing the Marriott hotel. The normally bustling lobby was empty and grimly dark. Eventually a staff person came to give us keys to our rooms and inform us that we had been given upgraded rooms. One advantage of flying during a global pandemic, you can get the good rooms normally held out for the best guests. I’d have 14 hours to spend in a two-story suite on the 40th floor.

There’s an old saying among freight dogs that “no matter what time it is when you takeoff, it’s breakfast when you land.” Crazy scene at the huge breakfast buffet. Quite a spread and at 7:30 a.m. but there was no one there to take advantage of it but the two of us, waited on by about six staff members. We sat by the large picture windows and watched empty commuter buses and trains pass by. They assured us that there were other guests in the hotel but we never saw another person.

The evening flight back to Germany was made shorter by the headwinds that had hurt us on the way out, so much shorter that we landed about a half hour early, apparently a half hour before the ground personnel that meet the airplane show up for work. Short staffed during the local quarantine we sat in the plane for 25 minutes after everything was shut down waiting for a ride in. Again, I looked around for the pampered red-carpet treatment given to commercial pilots. I think it was last seen in 1986.

Let me say at this point that our treatment in Europe was quite different from the treatment of my coworkers in Asia, particularly those choosing (yes, it’s optional) to fly through China. Our normally nice hotels have been replaced in China with government-commandeered travelers hotels that have probably never seen a western guest. In other places we stay in hotels that are internal to the airport, transit hotels, where you don’t clear customs and theoretically don’t enter the country.

In a couple of places, Shenzhen and Dubai for example, they have instituted nasal swabbing tests which have been described as a footlong Q-tip inserted in your nasal passage until it reaches your brain. It’s brought grown men to tears and crews are now standing up to the treatment, refusing to take the test and being put on the next plane out of town, although reportedly they have been threatened with having their passports confiscated, visas canceled, and criminal action against them in China. We have crews flying in and out of China twice a day and they will be subjected to these tests each time, even if they are just passing through. You really have no assurance over the training of the person administering the test. I don’t blame people that just say no.

If you think this through, what will they do to you if you are found to be positive on one of these swabs? And let’s not forget that there is a certain amount of false positive results in the test. Are they likely to send you to a nice hotel to wait it out or to Peoples Medical Center number 12 with a busload of other infected and contagious people where you receive questionable medical care or at best not along the standards we are used to in our country?

Other crews have reported being commanded to stay in their rooms while hallway guards make sure that the rules are enforced. Three times a day there is a knock on the door, they open it and find a tray of food. No hotel gym, no walk around the property, enjoy your room. The situation changes daily, sometimes for better, sometimes for worse. The companies that are operating are continually adapting to the situation and making the best out of things.

Our flight home had another eye opener. Normally when we cross the Atlantic, there are flexible airways in the sky that are referred to as the North Atlantic Organized Track System (NAT-OTS) but we pretty much just refer to them as the tracks. They are adjusted twice a day to suit the swarm of aircraft that are typically all going in one direction to give them the most wind-efficient routing. It’s not uncommon to fly hundreds of miles out of your way to avoid a headwind or to catch a tailwind. In the evening, the tracks go from west to east, and in the morning and afternoon, the tracks flow from east to west capturing most of the North Atlantic traffic.

On a typical day, there are 2500 flights crossing the Atlantic on the track system. Each plane is separated, roughly 10 minutes in trail behind the plane in front of it, and 60 miles or one degree of latitude from the plane next to it. With improved GPS capability, those distances can be shrunk even further to accommodate more airplanes. Twenty-five-mile lateral separation will soon be the norm. You are vertically separated by 1000 feet, and this is for the altitudes from 30,000 to 41,000 feet. Tight margins but a lot of airspace to operate in.

We plot the tracks on a paper chart or our iPads and it is not uncommon to have six or eight tracks active at a time to accommodate all of those planes with one reserved for opposite-direction traffic. On the night of our crossing, there was only one track in each direction, a direct reflection of the lack of traffic crossing the ocean with all of the airline groundings and travel restrictions in place. As I write this on March 31, I see only one track altogether. This is a very sad state but probably what we need to fight the pandemic.

So, I am now back at home, probably my first trip ever to Germany where there was no beer available, a testament to the gravity of the situation. I worry about two things. Did I bring a contagion home to my family and can I go back to work on my next trip with a certainty that I will not get sick over there? Initially, anyone traveling from overseas was asked to self-quarantine for 14 days. That was eliminated for transportation workers because I guess the virus recognizes the essential nature of our services.

I talked to a friend who is a pulmonologist dealing firsthand with these things and expressed my concerns as well as my desire for a test. He said that the virus is so prevalent worldwide now that your odds of catching it here are no less than your odds of catching it in Italy for example, one of the layovers on my next trip. We are all self-quarantined at this point so the 14 days for international travelers really doesn’t mean much. As for a test, no chance. There aren't enough to go around in our area and if you are asymptomatic, you don't qualify for one.

His advice was to wash my hands as often as possible, and to no matter what, avoid touching my face. He said I needed to keep an eye on co-workers and we all needed to tell each other when we see someone scratching or touching. If you must scratch, his advice was to wash hands before and after. I have to say my face as never itched as much as it does now after hearing not to scratch. He asked me to pass this information along to everyone. So here it is.

So, I left home and hearth and took a trip to Europe. Did I really exercise an essential function in the big scheme of things or did we just carry rubber dog doo from Hong Kong as Tom Cruise was warned about in Top Gun? Our company claims to carry 3 percent of the world's GDP and 6 percent of our country’s at any one time. What would happen if we all stayed home?

I think as flight crews, we all accept that we have a little more risk traveling in these times and as flight crews carrying freight and not people, we constantly reflect on the fact that we have a steady paycheck and some level of security that our brothers and sisters in the passenger world do not. Much of the world will be in economic straits pretty soon and long after this is all over. Keep us fed and watered, and we'll perform. Were we to stay at home and the transportation systems collapsed, recovery and survival would be jeopardized that much more? I’d like to think that we did some good, carrying medical supplies and pharmaceuticals along with the rubber dog doo. Time will tell.