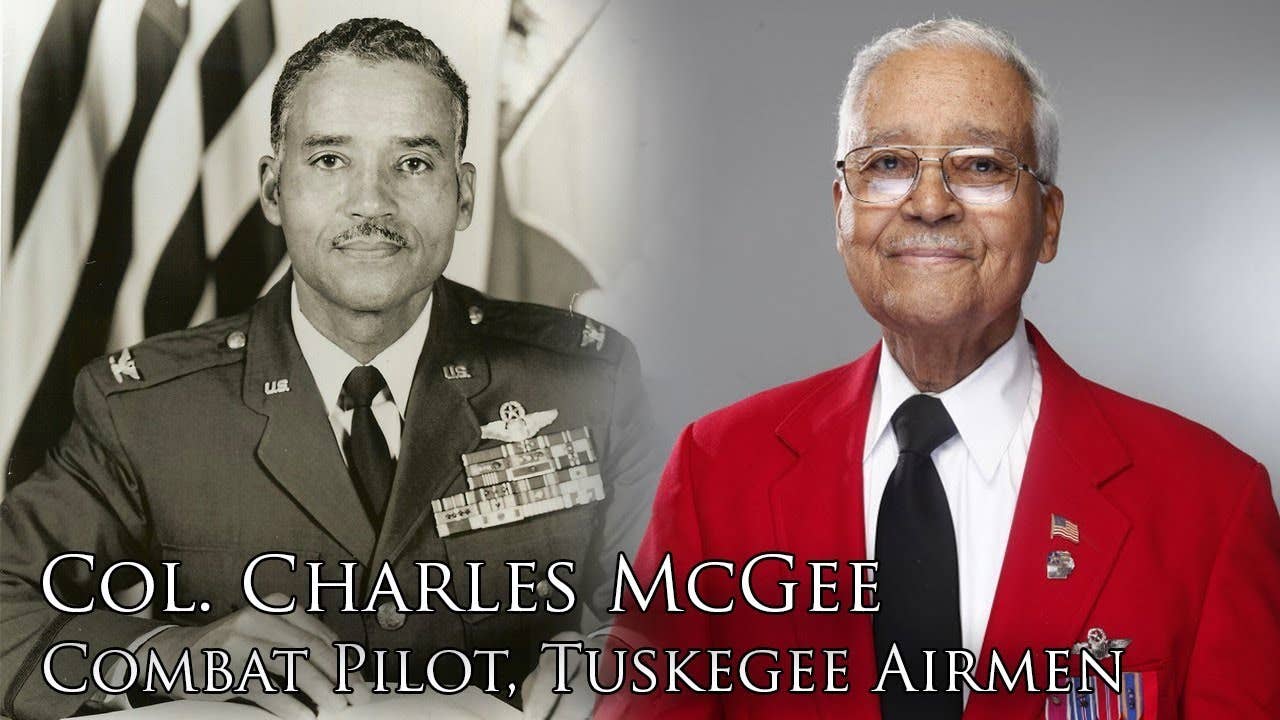

Gen. Charles McGee: A Remembrance

Gen. Charles McGee of the famed Tuskegee Airman died last week at 102. As anyone who met him will recall, he led a long life of dignified, quiet heroism.

Credit: American Veterans Center

As was anyone who ever had the honor to meet him, I was saddened to learn of the passing of General Charles McGee last week at age 102. Like many journalists, I had the chance to talk at length with McGee about his experiences as a Tuskegee Airman, and the rest of his distinguished 30-year Air Force career.

He was in his mid-90s at the time, and our phone conversation lasted well over an hour. I asked pilot-specific questions about flying Mustangs in combat, and even though the vast majority of his interviews over the years have been from the perspective of non-pilots, he was able to seamlessly shift his focus back half a century to comprehensive explanations of events and operational strategies. His memory for detail was incredible.

He was also able to articulately reflect on his experience as a young African American man learning to fly, in wartime, in the deep South of the 1940s. He talked of how he relished the opportunity to fly, and navigated racial discrimination with wisdom and dignity beyond his youth.

My opportunity to appreciate what Charles McGee experienced started decades before I met him—before I even knew anything about the “Tuskegee Project.” It was late winter in the mid-1980s, and I was on a VFR adventure trip in my little Grumman AA1-B, making my way from New England to Florida. Deteriorating weather had forced me to choose a random airport from my chart as a safe harbor—I didn’t even know how to pronounce “Tuskegee.”

No one was around when I landed, so I’d spent a night of fitful sleep in the baggage area of my airplane. Besides the creepy fog, the airport beacon creaked like a horror-movie coffin hinge with every rotation. In the distance, a chicken farmer apparently subscribed to the theory that hens would lay more eggs if he piped scratchy music into their roost—all night long. Eerie.

As the sun rose and started its slow burn on the fog, I gave up on the idea of more sleep and wandered around. A small plaque under a flagpole piqued my interest. Hmm. Apparently, Tuskegee was a training site for Black aviators during World War II. Never knew that. Never knew there were Black pilots during World War II. I strolled the open parade ground where weeds sprouted between the rotting concrete. It was bordered by rows of rough-hewn barracks weathered in muggy Alabama air, paint curling up and windows brittle with age. I imagined the presence of ghosts. Heroic ghosts, wearing khaki and leather.

I had no way of knowing, but four decades earlier, a young Charles McGee—among hundreds of other cadets—felt his pulse rising with excitement as he first set foot onto this now-hallowed ground. Back then, the paint was fresh, the concrete newly poured and the air blatting with the sound of radial aircraft engines. McGee had lucked into the opportunity of a lifetime in Tuskegee. He was a young Black man in a white world, but he was about to become a fighter pilot.

The Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor on McGee’s 22nd birthday, Dec. 7, 1941. His life to that point had been spent mostly in the North, in Cleveland, Chicago, even Keokuk, Iowa. His father was a minister, and though McGee didn’t consider himself to have been well-to-do, he didn’t recall his childhood during the Great Depression as needy. “I was also fortunate that my parents and grandparents stressed the importance of a high school and college education,” he said.

McGee told me he didn’t remember much in the way of overt racism growing up. He graduated from Du Sable High School in South Chicago in 1938, and went to work in the Civilian Conservation Corp in northern Illinois to help finance an engineering program at the University of Illinois, beginning in 1940. For extracurricular activity, he joined the Reserve Officers Training Program (ROTC) and was a member of the Pershing Rifles there.

War was in the air, and word buzzed through the Black community that an experimental Army squadron of negro aviators was being formed. Though he had never flown, McGee was intrigued, especially when he learned that recruiters were looking for mechanics, crew chiefs and even pilot candidates. With his engineering background, he thought he might have a chance to get in on a good thing. Then, while riding with his family to sing at a church in Chicago on his birthday, word came over the radio that the United States was no longer on the sidelines. The “what-ifs” had been answered. McGee applied for a pilot’s slot, passed the exams in April 1942 and on October 27, he was sworn into the reserves. A few weeks later, he got the call to report to a small town in Alabama named Tuskegee.

The summer of ’42 had further significance for McGee. He married his wife, Frances, on October 17—so time was spinning madly for the young man over those few months. And then, he was on his way to live in the highly segregated Deep South for the first time in his life. When we talked close to seven decades later, he looked back philosophically on the experience. He said of the success of the Tuskegee Project: “It was an achievement, without violence, that advanced the military and the country. I had been taught to look at the positive and eliminate the negative—not dwell on it. We all believed in our capabilities and talents. So don’t let discouraging moments deter you. That’s a message I deliver to young people.”

McGee’s first flight instilled a transformation in him that all pilots know. “I just fell in love with flying,” he said. Primary training was in Stearman PT-17s on a grass strip outside the city of Tuskegee. He transitioned to “Basic” in Vultee BT-13 “Vibrators” and “Advanced” in the legendary North American AT-6. McGee graduated from Tuskegee in Class 43-F. One of his most important lessons? Lay off fried foods at breakfast to avoid airsickness.

Pilots were needed desperately, then, so things moved fast. His first check flight had come in February 1943 and his final flight as a cadet was in June. On June 30, he’d earned his silver Army Air Forces wings, and he had his first flight in a Curtiss P-40 fighter on July 6, 1943. Less than five months from fledgling trainee to solo pilot-in-command of a V-12-powered bird of prey.

For a northerner, McGee understood the transition he underwent when crossing the Mason Dixon line. He was shuffled to the rear of the train car upon crossing the southern Illinois border, and much of his conversation with fellow Black cadets from the Deep South centered on what precautions were necessary to stay out of trouble. McGee was accustomed to the culture in Chicago, where Blacks were unwelcome at certain barber shops and restaurants, but in Alabama, the consequences of a misstep were much more dire, and he knew it. McGee said some southern Blacks were deeply concerned for the way their northern classmates might react.

After graduation from Tuskegee, it was back north to Michigan’s Selfridge Field (named for Lt. Thomas Selfridge, the world’s first (official) plane crash victim, killed when Orville Wright plunged to the ground on Sept. 17, 1908, with Selfridge as a passenger). Selfridge Field was where the three squadrons of the 332nd Fighter Group were being formed—the 100th, 301st and 302nd. After combat training, the group transitioned from P-40s to mid-engine Bell P-39s and left Michigan in December 1943 for the long trek to Newport News, Virginia, from which they sailed for Italy. Their first base was in Montecorvino.

Much has been written about how the Tuskegee Airmen were kept from front-line combat duties. But some of that has to do with the airplane they were flying. Their first assignment was coastal patrol over the Mediterranean between Naples and the Isle of Capri. The P-39 was considered virtually obsolete by February 1944, and its un-supercharged Allison engine made it unsuitable for high-altitude combat. McGee’s first patrol was logged Feb. 28, 1944. Like the rest of the pilots, he was itching for combat. The next month, the group moved forward to Capodichino, but the mission remained coastal patrol. Without much performance above 15,000 feet, the P-39 just wasn’t the right airplane to engage the Luftwaffe.

Things started changing fast in May 1944, when the three squadrons of the 332nd were joined by the Tuskegee-trained 99th (already veterans of combat against the Luftwaffe over the Anzio beachhead), and incorporated into the 15th Air Force. The four squadrons of Tuskegee Airmen moved up farther to Ramatelli, Italy, to begin bomber escort duty. Best of all, they left their sluggish P-39s behind and welcomed the transition to the enormous, turbocharged Republic P-47 Thunderbolt. McGee first flew a P-47 on May 5, three weeks before the move to Ramatelli. But the group was to fly the P-47 for less than three months, transitioning in July to the legendary P-51 Mustang.

For pilots today, the way combat pilots in World War II routinely stepped up to a totally new fighter is a little startling. McGee said: “You’d just read the tech order, sit in the cockpit for a while to find the switches—and go.” Of course, with a single-seat fighter there could be no dual instruction, anyway. But the prospect of a 23-year-old launching from a pierced-steel-plank runway in a 1,700-HP taildragger with a huge four-blade prop remains pretty astounding. Especially when you consider that his first-ever flying lesson was a scant 18 months earlier.

And then there was the combat part.

The 332nd was assigned to bomber escort duty along with three other groups. The others, all with white pilots, had the tails of their airplanes painted yellow (52nd FG), candy-cane stripes (31st FG) and checkerboard patterns (325th FG)—for easy identification in the high-speed world of aerial combat. McGee said the decision to paint the 332nd’s tails red was mostly an accident of pragmatism. “For some reason, we had a lot of red paint,” he said. At first, the ground crews painted just the Mustangs’ rudders red. An unidentified 332nd pilot cavalierly suggested “That’s not enough,” and they ended up painting the entire tail red. The Red Tail legend was launched and still lives on today.

The mission was bomber escort, and the 332nd commanding officer, Colonel Benjamin Davis, was adamant that his pilots would stick to the mission. McGee said, “We had great leadership in Col. Davis; and he let everyone know that he’d court martial any pilot who’d go ‘happy hunting’ on his own.” The escort missions from Italy extended northeast to the infamous oil fields at Ploesti and other targets in central Europe, north to the German homeland, and northwest to targets in occupied France. McGee recalls that some missions would involve no contact with enemy fighters, while others would encounter very heavy resistance. No pilot was to attack unless ordered by his flight leader, and no leader was to order such an attack unless the German fighters were a clear threat to the bombers.

Somewhere along the way, said McGee, a 15th Air Force officer made the statement that no bomber escorted by the Tuskegee Airmen had ever been lost to enemy action. In hindsight, such a claim could never be verified—and its logic is questionable, at best. Escort missions often involved several groups of escorts picking up the bombers and then “handing off” escort responsibility at overlapping rendezvous points. No one was keeping score of precisely when and where a bomber might have been shot down.

But there is no denying that the 332nd established a remarkable reputation for its escort work, a reputation that led bomber crews to appreciate the appearance of the Red Tail Mustangs, whether en route, over the target or on the way home. One of the specialties of the 332nd, McGee said, was looking after strays—those bombers that had suffered combat damage or otherwise become separated from the protective formations of their squadrons.

As a result of this conservative strategy, you won’t find pilots of the 332nd among the top-scoring fighter pilots of World War II, but they did have their opportunities. On a bomber escort mission in August 1944 to an enemy airfield and nearby railway marshalling yard at Pardubice, Yugoslavia (now part of the Czech Republic), McGee was ordered by his flight leader to attack one of the Focke Wulf Fw-190s that was attacking the bombers.

“It gets over pretty quick,” he said. “I dove in behind him, and he ended up crashing right on the aerodrome.” Even close to 70 years later, McGee was quick to repeat that he was ordered to the attack by his flight leader—as if he still feared the wrath of Ben Davis should it sound as though he was off “happy hunting,” on his own.

Colonel McGee went on to a full career in the U.S. Air Force (formed as a separate military branch in 1947), serving in Korea and Vietnam. And not behind a desk. He said, “I’m one of the lucky guys. Out of 30 years of service I was actively flying for 27.” In all, he flew more than 400 combat sorties. He said he was privileged to be part of the Air Force, where integration was advanced on a practical level.

“We needed people based on qualifications, not skin color, and the Air Force didn’t have the money to maintain and operate separate bases. So we were integrated even before Harry Truman signed Executive Order 9981 on July 28, 1948, mandating desegregation of all services. The Air Force led the military, and the military led the rest of the country.”

When I talked with McGee in his 90s, and I asked him if he’d seen the Commemorative Air Force’s restored Red Tail P-51C Mustang, he chuckled and said he’d even flown in the jump seat with pilot Doug Rozendaal a few times. “I loved it. It was great to be able to go up and do a roll again,” he said.

I met up with General McGee last summer at EAA AirVenture 2021 at a press event marking the delivery of the first Piper trainer for the Red Tail Academy program. In great public demand at the center of a flurry of attention and activity, he was still the polite, humble man I remembered from our conversation, and the times I had spoken with him in person at airshows. A genuine hero; on more levels than anyone could know.