Good Gravy, There’s Another Paul?

Actually, there’s one less as veteran New York controller Paul Niles retires after 43 years at the console. If you flew in New York airspace, you heard the voice.

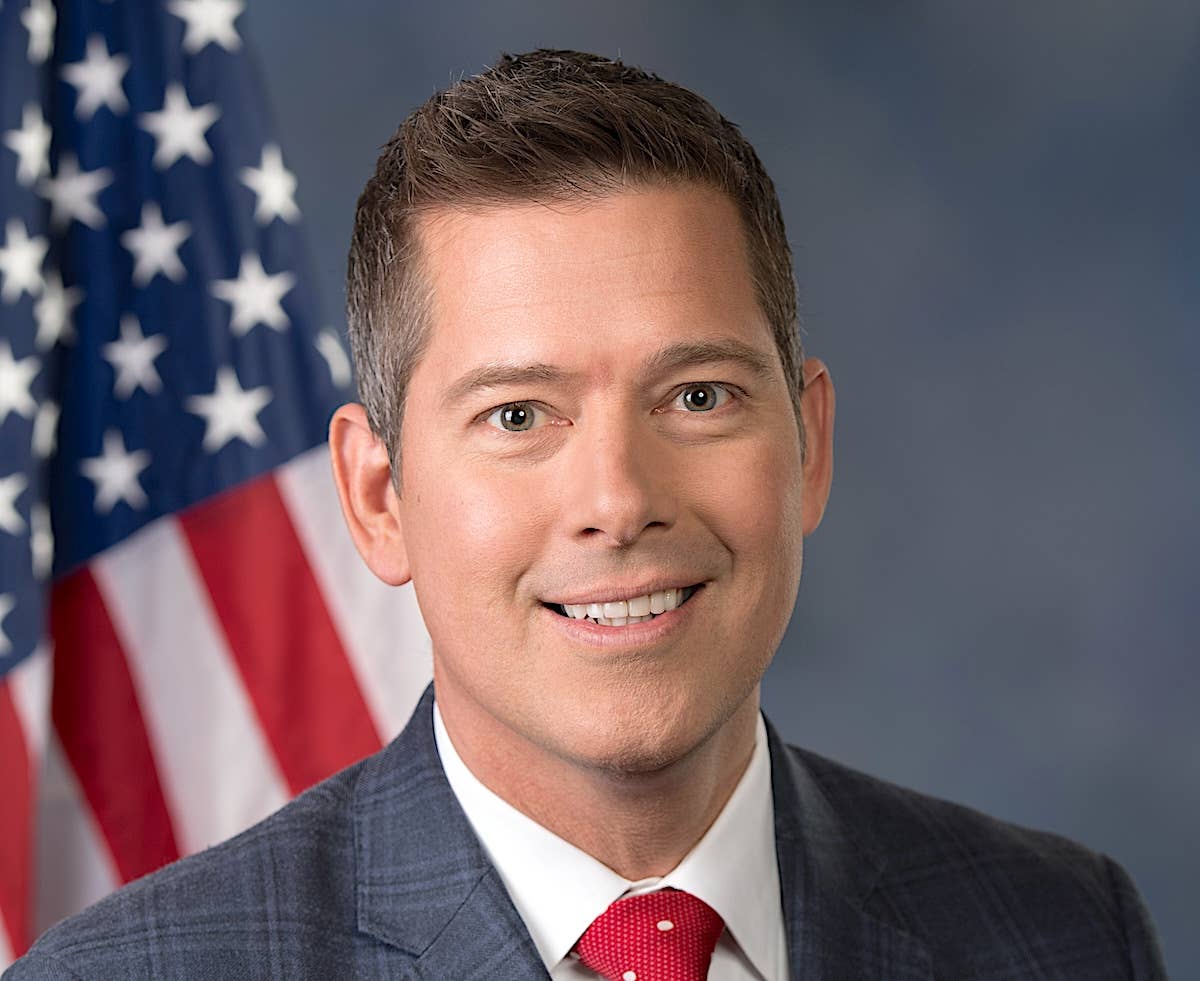

Paul Niles at N90.

Late afternoon sunlight danced through grimy venetian blinds as Ernie, the new kid from the AVweb mail room, nervously set an email on my Remington Model 7 typewriter. He eyed the Walther PPK, weighing down the rejected manuscripts atop my in-basket, as I scanned the message from reader Jim Mehling, a Falcon 50 pilot who’d been plying NYC airspace for 54 years. Mehling offered unsolicited praise for an unknown approach controller. “(He) is the epitome of an ATC controller in a high-pressure environment.” Mehling described the mystery controller’s “gravelly voice” and “demeanor on frequency as a top flight choreographer of the greatest ballet in the world …”

I thumbed my suspenders as Mehling continued, “This guy was vectoring a bunch of airplanes into Caldwell (CDW), Teterboro (TEB), and Morristown (MMU) around thunderstorms. He made it look easy from our side of the mic (and) never tied up the frequency needlessly with long winded instructions …” When someone asked his name, he answered only, “Paul,” and that he was retiring in three days.

Looking up, I told Ernie to scram so I could find this controller, calling himself Paul … as I once had. Armed with only two clues—a first name and where he worked—I began at the end and called New York TRACON (N90). I must’ve asked the right questions to the right guy, because minutes later I knew the controller’s name: Paul Niles, age 61, grew up in Queens and spent four decades bouncing from one control tower—Army and civilian—to another, until landing on Long Island in Westbury, NY, where he’d spent the last 19 years of his 43-year ATC career.

You grease the right FAA palms and you can glean anything; that ASR-9 antenna rotating atop my garage, for instance. Now, I had Nile’s phone number, so I called him. A deep, Sidney Greenstreet-like voice, combining an amused New Yorker accent with Louisiana jazz-infused vowels, told me I’d found the right Paul. Wasn’t long before I quit sounding like a 1940s B movie and Niles and I swapped ATC tales—his far superior to mine.

Like me, this Paul had left the New York area to join the Army, he at 17 in 1977, me at 18 in 1972, and that’s where our stories diverged. Niles became an Army air traffic controller. His goal was to serve his enlistment, muster out, and attend college, but on August 3, 1981, PATCO—the ATC union that thought it could strike but couldn’t—walked and instantly created 11,000 FAA job openings. Niles, an Army controller in an organization with a no-strike policy stricter than the FAA’s, was loaded onto an Army King Air (U21) and flown to Dallas, where he said, “it was eerily quiet.” The dearth of qualified controllers having brought air commerce to a crawl.

Paul certified on all positions in the Dallas Love TRACAB (combination tower and approach). But using military personnel to temporarily plug gaps left by fired strikers was an unsustainable plan. So, the FAA offered Niles, who was approaching the end of his enlistment in 1982, permanent employment, including an eye-popping pay raise. He left the Army and, with no break in service, spent the next three years in Dallas, followed by two in the Albuquerque, New Mexico, tower and TRACON, before returning to Texas for 15 years in Houston’s tower and TRACON. In 2002 he transferred to NY approach on Long Island, working the Newark sector, N90’s busiest of its five. It covered much of northern New Jersey, a few airports west of the Hudson River, and the eastern side of the Pocono Mountains.

His distinctive voice followed along on frequency, prompting pilots who’d heard him in the South to ask, “Where do I know you from …?” He’d become an ATC legend, and in September 2021, after 19 years at New York approach, he retired, five years past the so-called maximum retirement age of 56.

How’d he bust that ceiling? Easy. The FAA was, usually has been, and always will be, short-handed as well as short-sighted. N90’s full complement is 310 controllers. When Paul hit the out-you-go age limit, the TRACON had 130 controllers who for years had been working six-day work weeks and frequently 10-hour shifts. Unsurprisingly, the FAA offered to wave its magic waiver wand and retain him for “one more year.” He reapplied for that extension each year for five until finally saying, “So long, and thanks for all the free pens I’ve pocketed over the decades.”

Making a classy exit after a long run is important. Paul Niles says his last ATC instruction was to a Newark Liberty International Airport inbound: “United 1662, descend and maintain 5000.” He could’ve dropped the mic and walked off stage but added on air that this was his final day of a 43-year career. No studio audience to stand and applaud, but those on frequency thanked him for his service. To which Paul replied, “Gonna miss you guys.” Whether United 1662 would get lower or not was then someone else’s responsibility. Like Elvis, Niles had left the building.

Blown away by his abnormally long ATC career in some of the most prestigious facilities in the world, I thought I had the full story, enough perhaps for a Hallmark movie. Then, retired air traffic controller, Paul Niles, sent me a picture of him beside his Beech 55 Baron parked at Long Island MacArthur Airport. “So,” my return email asked with undisguised awe and more than a little envy, “you’re a pilot as well?” Yes, he replied, been flying for 40 years. He’s an ATP plus—because he could, and there’s a lot of water near Long Island—also holds a Single Engine Sea (SES) rating.

Today, one less Paul works air traffic, but should you spot him in an FBO lounge, his Baron on the ramp, feeding at the avgas trough. Grab a seat and plan to spend hours listening to one of the most interesting, and accomplished, pilot/controllers I’ve ever encountered: Paul Niles, retired ATC.

Now, where’d that Ernie go? Kid’s gotta show me, again, how to change this typewriter ribbon ….