If The Wright Brothers Started In The Age Of Electric Airplanes

Dingbat hype existed then, but not so much about airplanes because no one knew what they were. Electric airplanes are a whole ‘nother thing.

Kitty Hawk—The Wright Cycle Exchange announced today that it has firm commitments from several airlines to purchase 50 Wright Flyer machines with options on 100 more. The airline companies will be announced as soon as such companies have actually started and it can be determined what an airline actually is, which is expected by the first quarter of 1904, second quarter at the latest.

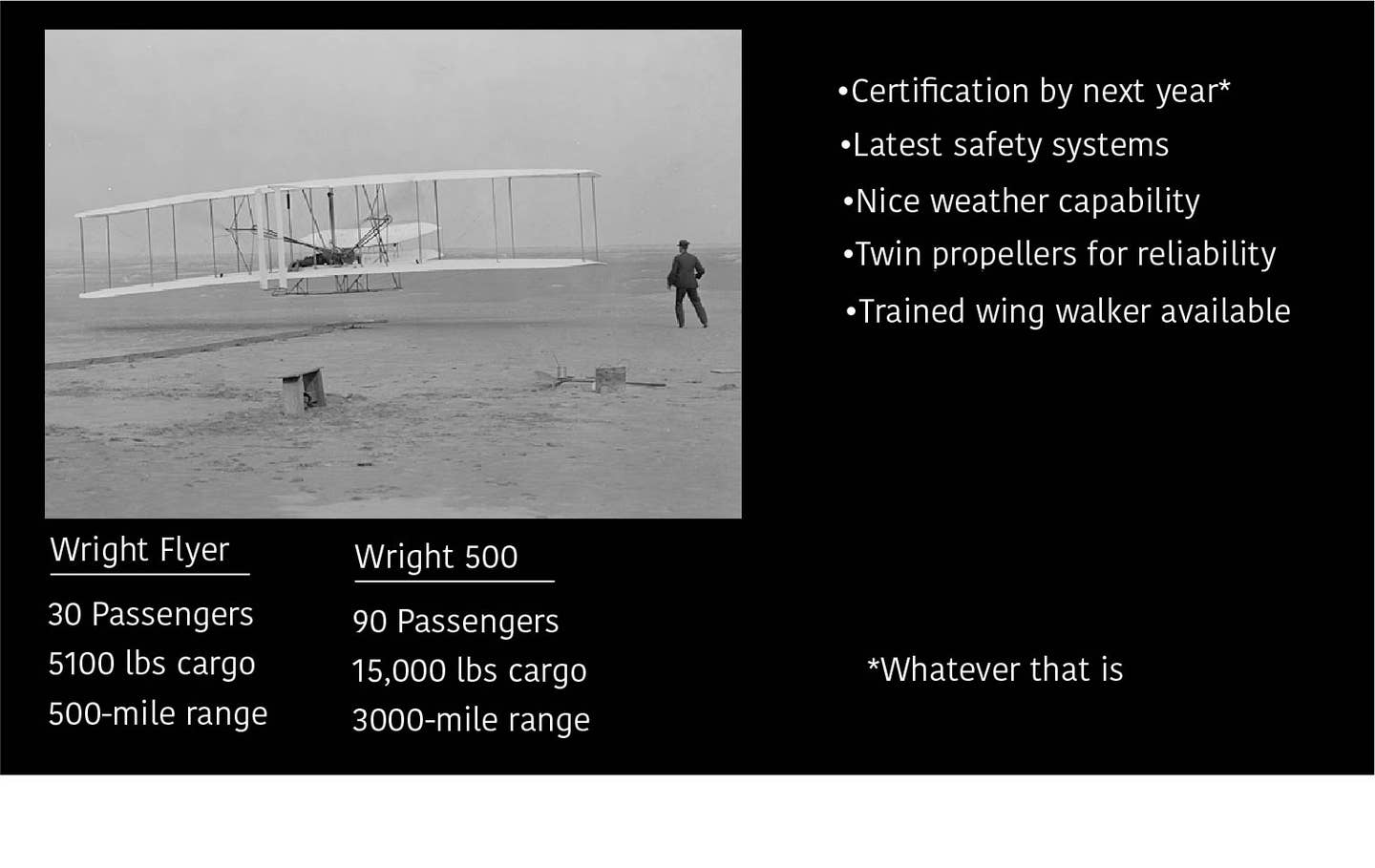

The company said the Wright Flyer, powered by a single 600-horsepower Taylor Dragon engine, is capable of carrying 30 passengers over a distance of 500 miles. The Flyer 500, which the company is taking orders for with deliveries in the first quarter of 1905, will carry 90 passengers over a distance of 3000 miles at a cruising speed of 400 miles per hour. Although the engines, materials, engineering and aerodynamics for the 500 don’t exist, they are expected to by the fourth quarter of 1904, according to the Exchange.

Cycle Exchange Chief of Business Continuation Wilbur Wright said the machines are “game changers” that would reinvent aeronautics and aviation, a heretofore nonexistent field. The Wrights telegraphed the news to their sister in Ohio: “Success four flights Thursday morning. Home by Christmas. Meet us at the FBO in Dayton 1:30-ish.”

A little grim aviation humor that’s probably uncomfortably close to truth. After all, American business has always been characterized, at its outer fringes, by a little flashy exaggeration. In aviation, we sometimes call this flat-out delusional fabulism, but this is an unimportant detail. What matters is that when delivery dates are given in quarters, you know the real delivery date is sometime between never and an excruciatingly drawn-out bankruptcy followed by a fire sale for three cents on the dollar.

Inevitably, I thought of this not-that-far-out fantasy when Miles O’Brien and I were talking about his recent PBS NOVA program on electric airplanes. You can see the program here and our recorded interview here. And I would recommend watching the NOVA program twice because it has some detail I missed the first time around. Miles had sent me a preview version before it aired and after I saw it, we shared a mutual groan over the distinct difficulty and lack of satisfaction in covering this emerging field.

I’ll start with a declaration. In my view, electric airplanes are a genuine technological wave. They are here; more are coming. I’m not hung up on the battery barrier. It will be overcome to the extent that battery-powered aircraft will have a presence of some kind, but won’t be the wide spot in the market unless developments take the technology well beyond the 5 percent gains we’re seeing annually now. Not much is in view to suggest this will happen. But then powered airplanes themselves weren’t in view in 1890.

To assume that some versions of hydrocarbon hybrid or perhaps fuel cells won’t eventually make these airplanes more fully functional is to assume progress is frozen and gasoline piston engines are as good as it’s ever going to get. That’s probably true for us fossils doddering into the end of our flying careers, but how about the 20-something taking flying lessons today? He or she will navigate a different world.

Which is why covering this apparent revolution feels like serving up a bowl of steam. Just this year alone—two quarters worth—we’ve published 16 stories on electric aircraft of various kinds. This week, we published this one. It describes how Ravn, a restart airline company in Alaska, plans air service with an electric airplane called the Airflow. Ravn proposes short-haul trips to relatively closely spaced villages. So far so good.

But what Airflow has so far is a press release. It’s not even to the point of a concept demonstrator, something it plans to do with a Cessna 210 and which Ampaire is already doing with a Cessna 337. (This is covered in the NOVA program.) Like others in the modern mediascape, we cover these stories as straight news without comment, leaving the reader to decide on their legitimacy. I’m beginning to think such reports need a warning label or some kind of five-level credibility index. “Caution: Reading this story may give you the impression that you’ll be flying on an electric airplane next month or next year. Or the year after that. Restraint is recommended.”

The profusion of startups and the stories they ignite may have a cumulative effect. If you read enough of them, you may begin to believe that things are further along than you imagined. The reality is messier than that, uneven and almost impossible to pin down by even an informed journalist asking the right questions. Consider this fact: I’ve covered this field as aggressively as resources allow and I’ve flown electric airplanes exactly twice for barely an hour in six years of trying. And I had to go to Slovenia to do it.

The true, washed-in-the-blood electric acolyte may concede the hype but also believe the entire enterprise will reach critical mass suddenly and you’ll be stepping on a Joby air taxi instead of hailing an Uber. No one can say when this will happen or even if it will.

But I’m pretty sure it won’t be suddenly or sooner than we think. But I’m also lukewarm sure it won’t be never. Betwixt the two is the challenge of playing coverage just the right way. I doubt if we’re getting it right.

In all the discussion about battery technology, about regulation and certification, noise, payload, cost and range one fact is in such plain sight that it’s rarely discussed: the aerodynamic advantages of distributed electric power. Powerful, reliable electric motors are already allowing these machines to do something previous aircraft could not, which is to take off and land vertically or nearly so without sacrificing high cruise speed to an unacceptably high noise signature. If Joby’s claims are correct—and I remain skeptical until they desist from being so secretive—this has been demonstrated to near the point of certified, production aircraft. But between “near the point” and certified is a yawning gap that could take years to bridge.

Electric propulsion also encourages the inevitability of autonomous flight for both people and cargo. Virtually all of these aircraft are being designed with automation as a fundamental assumption with a human pilot inserted as a temporary concession to passengers we imagine to be too fearful of trusting a robot instead. Rational or not, the same thinking assumes passengers can’t or won’t parse that most accidents are caused by homo the sap doing something stupid or wrong in the cockpit. Will this change? I’d say yes, we just don’t know when.

Also lost in the noise is a critical juxtaposition. It’s one thing for NASA to strap 20 motors to an airplane wing to prove a concept and quite another for the boys and girls down in the shop to build such a thing profitably. Never mind fantasies about automated factories, for short-term viability, these ideas will have to show at least some inkling that their economic outlook is worth the trouble and expense.

Probably what gives us agita about covering this field is our inability to understand—or sometimes even see—the intersection of the technology with the business plan. It’s not so hard to understand that an electric airplane with a 40-minute, 150-mile range can do something, but is that enough to ignite enough sales to sustain whoever has invested the equivalent of the GDP of Argentina in this grand, world-changing vision? Worked for the iPhone, right? In aviation the odds are rather more dismal.

Not to be a glass-half-empty kinda guy, but the last two big craters we saw in aviation after frenzied press coverage were Eclipse and Icon. No need to review the dreary history, but both of these airplanes were sold as disruptors, if not game changers, to fail miserably in resisting a tiresome cliché. Neither of the airplanes themselves were fatally flawed, but both foresaw vastly larger markets materializing much faster than the plodding pace of reality would allow. The business investments were hopelessly out of balance with the revenue that sales could possibly generate, thus narrowing the enterprise to a one-way lane to deep retrenchment if not bankruptcy. In Eclipse’s case, it was a flawed concept aggravated by mismanagement.

Joby, the imagined leader in the urban air mobility … I almost said market, but there is no demonstrated market. Let’s call it a concept. Joby is thought to have $6 billion at its disposal and envisions making millions of these aircraft to save, as the company founder JoeBen Bivert says, a billion people an hour a day. Six billion, by the way, is a billion less than the developmental costs of the Boeing 777. For the magnitude of Bivert’s vision, that may barely be a down payment. Watching this company for the next decade is going to be riveting.

Absent my imaginary warning label then, my advice to the discerning reader or viewer is two-fold. First, accept all this press-release originated news about electric airplanes for what it is: long-shot business ideas based on genuine technological underpinnings fertilized by high aspiration, with an emphasis on the gauzy connotation of that word. Some of it is a lot less gauzy than the rest of it. Second, a belief that something won’t happen because it hasn’t happened yet is the lazy refuge of the ignorant cynic, but at least another opportunity for me to cheap shot Lord Kelvin for his insistence that heavier-than-air flight would be impossible.

In our coverage here on AVweb, we’ll continue to try to thread this needle between shameless hype and unpleasant reality. Rather than confess anything so naïve as actual hope, let me just say the law of averages suggests we’ll get it right once in a while.