Kobe Bryant Crash: Absolutely Nothing New To Learn

Here’s a plaintive hope we’ll some day learn to step up and stop expecting the FAA and the NTSB to save us from ourselves.

As I was sitting through the NTSB probable cause hearing on the Kobe Bryant crash last Tuesday—all four hours of it—I felt like I was watching "A Few Good Men" for the 39th time. It’s on every other night on my cable system. I know what’s going to happen, but I still like watching Jack Nicholson throw shade at Tom Cruise not being able to handle the truth.

I could say the same thing about how we in the aviation business think about accidents like the tragedy that killed Bryant, his daughter and their companions on Jan. 26, 2020, on a foggy hillside in Calabasas, California. When I edited the news video, I played it as straight news and you can see that here. But during the hearing, I was wondering where the board was going to go with this while analogies for futile gestures came to mind having to do with rearranging the furniture on a doomed ocean liner. Which is to say you can slice it, dice it, rearrange it and examine it under a microscope and there is nothing new to learn from this accident that we haven’t learned a hundred—several hundred—times before.

Pilot suffers spatial disorientation, loses control and everyone dies. These facts are not in dispute, as Kevin Bacon’s Captain Jack Ross said. But the board couldn’t resist a foray into the miasma of trying to explain why he intentionally ventured into such hazardous straits, theorizing that that self-imposed pressure played a role. Continuing my cheesy courtroom analogies, facts not in evidence. But never mind, they spent a fair portion of an hour debating the wording and where to place the comma in a sentence that was veering dangerously close to saying “probably likely.”

Saying the pilot was under self-induced pressure is, at best, evidential lemon meringue. It suggests there’s a reason when none is evident or that there’s a psychological underpinning for the unexplainable. We will never know what reasoning—or lack thereof—the pilot employed to jam himself into a corner he couldn’t exit. The NTSB was right to investigate the accident as it did and to present its findings as it did, it’s just that the findings are the same deary repetition of the same ill-advised judgement we see a dozen times a year.

Had Kobe Bryant not been a celebrity, this accident wouldn’t have merited a probable cause hearing and might or might not have resulted in an NTSB recommendation. Yes, the agency responded to the expectation that the public seeks action after somebody famous dies in an aircraft accident. That’s as it should be because even though it’s fashionable to deride Bryant as just another coddled, overpaid athlete, his achievements on and off the court touched many people in the city of Los Angeles and throughout the world. If a high-profile accident merits high-profile attention, the potential benefit to aviation may be worth the glare.

Except this time, we already knew all this. We knew that pilots blunder into weather they can’t handle, we knew pilots are predisposed to finish what they start—“plan continuation bias” in the dry taxonomy of psychological labeling—and we know to the extent of nausea-inducing repetition how the inner ear works. Perhaps in place of self-imposed pressure, the NTSB should invent a new contributing cause:

This could be you.

That’s right. Even if you’re a skilled pilot, one who stays current on stick and rudder, collective and cyclic, knows procedures cold and your judgment is always sound, deep down in places we don’t talk about at parties, we know our reptilian brains are capable of doing the inexplicable with results that are unexplainable.

The misinformation loop that so characterizes contemporary life had it that Bryant had fired other pilots who wouldn’t fly trips when he wanted to go. Facts not in evidence. Or that the company had a reputation for ignoring regulations and operational guidelines. Facts not in evidence. These wisps are there for the grasping. But they are just rationalizations to avoid accepting the fact that pilots make mistakes or do ignorant stuff and no amount of experience, training, regulation, 299 click-greedy YouTube channels devoted to aviation accidents will change the fact that the aviation community has had the means to avoid accidents like this for many years.

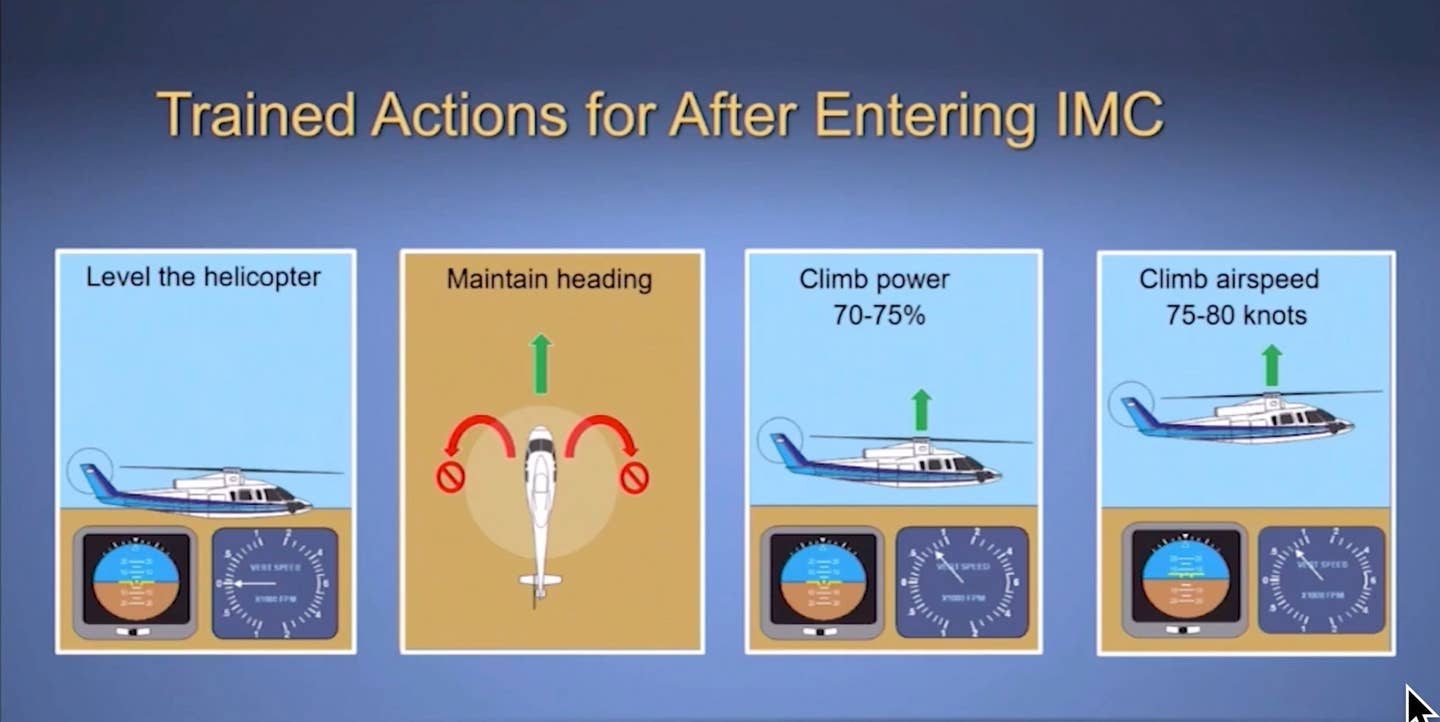

The NTSB recommended exploring better ways to train recovering from inadvertent IMC encounters and suggests an evaluation of technologies that might do it best. It also wants flight data and cockpit voice recorders, both to enhance accident investigation and to feed data to routine review of routine operations. The idea is to detect outliers—both in pilots and procedures—before they became accidents.

I have no opinion on the efficacy of such things. Gadgets have reduced accidents in the past, GPWS and TCAS come to mind, so I wouldn’t dismiss them out of hand. But the larger issue remains homo the sap in the loop just making bad judgements. That may argue for more scenario/awareness-based reminders like this one done by the U.S. Helicopter Safety Team, or this series by Helicopter Association International. Perhaps pilots don’t need full-blown, half-day safety sitdowns so much as they need succinct reminders about accident trends that are killing people. Most of us, I think, can figure out the rest.

Looking over comments attempting to rationalize or explain the Bryant crash, I’ve noticed a lot of fine point dissections but I think the thing is just simpler than that. I also think we should stop looking to the NTSB or FAA to figure this stuff out with more rules and more recommendations to save us from ourselves. As individuals, we already know what to do; we just have take personal responsibility and do it with the same determination that got us to become pilots in the first place.

But then you already knew that.