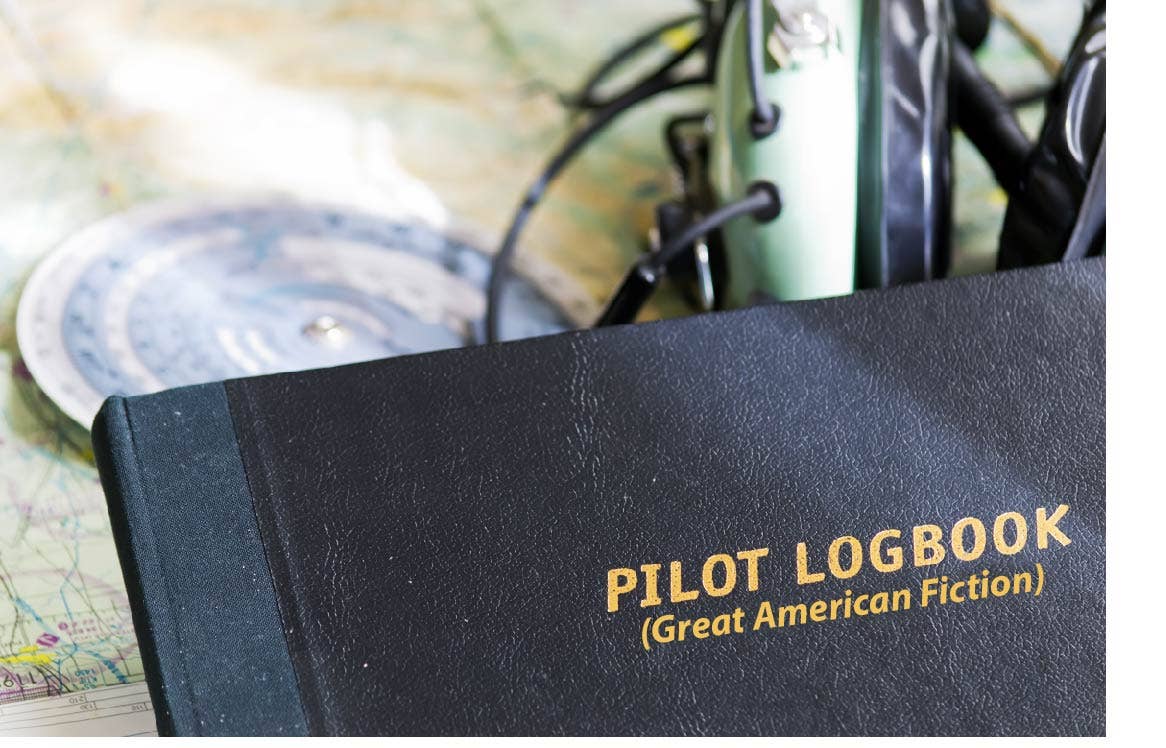

Logbook Entries: Fact, Fiction Or Fantasy?

In today’s installment, Berge constructs an elaborate defense for flying under bridges. Bookmark this. You may need it someday. (And please buy a copy of Bootleg Skies.™)

Once again in an egregious snub, the Nobel prize for literature did not go to an aviation novel, such as Rick Durden’s "The Old Man And The Seaplane," about an aging CFI’s lone struggle against an enormous walleye on a lake up in Michigan. Not aviation’s first rejection from the Swedish rodeo. Instead, Nobelers went with Peter Handke, who’s not even a pilot.

Apparently, Peter “explored the periphery and the specificity of human experience, blah, blah, blah...” Big whoop, but can Pete explore the periphery of landing a Carbon Cub on an Idaho sandbar in a crosswind? Or the specificity of the human experience while teaching steep spirals to a commercial student who’s trending green and wondering why she has to do this maneuver and will never attempt it again after the check ride? I think not. Cherish your laurels, Herr Handke, knowing serious fiction isn’t found in dusty tomes that Lit majors pretend to read but, instead, inside a pilot’s logbook.

Logbooks represent a sacred bond between aviators and insurance companies, but as a flight instructor I’ve seen a lot of weird stuff, including creative math, on those pages and put some there myself. Of note was the non-instrument rated pilot who handed me his logbook in preparation for a flight review. It read like a dream diary. The 97 hours he’d racked up in ten years reflected the experience of too many pilots who love aviation but for various reasons don’t fly enough. Flipping a page, I paused at remarks for a solo flight in a Cessna 150: “Flew into the clouds today! Scary!” Lesson learned? Perhaps, but despite the exclamation points, such an entry could come back to haunt during a postmortem. Being dead does not excuse you from FAA scrutiny.

I’m not a lawyer but have watched enough Matlock reruns during COVID to imagine defending this client in the NTSB Star Chamber: “Your Honor, my client wasn’t attesting to the literal truth of continuing VFR into IMC when he endorsed this entry but, instead, expressed his desire to one day explore not merely the periphery but the specificity of allegorical cloudness.”

While it’s swell to record personal observations such as “greased it on today,” or “read Berge’s latest aerial bodice ripper and inspired me to quit flying,” it might be prudent to avoid logging admissions of possible guilt. Save such actionable braggadocio for the Pilots Pub where absolute truth is excess baggage.

My client and I spent additional ground time, reviewing FAR 91.155 Basic VFR Minimums, a regulation Mark Twain dubbed “chloroform in print” but with relevance. All of this introduces a tortured segue to the stale news about retired FAA employee, Martha Lunken, busted for allegedly flying her alleged Cessna 180, beneath an alleged bridge too far from reason. Plus, something about ADS-B, which I really don’t understand but am glad it isn’t in my airplane that lacks an electrical system.

We’ve all had time to dissect this incident that underscores the ethical principle learned in the 4th grade that, if caught, actions have consequences. I suspect the Ohio Bridge Authority will banish Martha to the Isle of Misfit Pilots in the Dry Tortugas in vain hope of discouraging copycats. That said, I question the logic and, indeed, whether Part 91 prohibits bridge scooping. Here’s my amicus defense argument bolstered with an unlikely, hypothetical scenario.

If operating VFR inside Class G airspace—the Good space—the Cessna 180 would’ve been required (daytime) to “remain clear of clouds.” Within Class E airspace, less than 10,000 feet MSL, VFRs shall remain 500 feet below clouds. I’ll speculate without the benefit of facts but with the confidence inherent in ignorance, that no clouds were under the offended bridge. Perhaps, though, a low overcast hovered above, leaving the pilot no choice but to duck beneath the ceiling, with the only prudent strategy being to skim the river, where someone had placed a bridge, through no fault of the pilot. If viewed as an emergency situation, and I’m not saying it was, then 91.3 grants the PIC authority to deviate from any Part 91 rule, including 91.13 Careless or Reckless (your choice) Operations While Surrendering To Temptation. Yeah, if real clouds were an issue, then an IFR clearance would’ve made for a safe and mundane exit. We’ll ignore reality to continue teasing out my hypothesis.

With cloud issues resolved, obstacle clearance gets sticky if one misinterprets, as the FAA might have, 91.119 Minimum Safe Altitudes. It says, “except when necessary for takeoff or landing,” airplanes shan’t fly lower than 1000 feet above—key word—the highest obstacle within 2000 horizontal feet, especially if it contains security or doorbell cameras. I submit that the unjustly accused respected 91.119 by operating beneath the obstacle bridge and, therefore, no violation ensued. Martha must fly free, as the bumper sticker on my Prius reads.

Lacking obstacles, 91.119 contains another stinger, protecting any “open-air assembly of persons.” Think concerts or naked beach volleyball. Flight across assembled or disassembled persons requires at least 1000 feet clearance above the “highest person” in the crowd, which is hard to determine ever since Woodstock so add a few vertical feet when circling Burning Man Festival.

My point? If you and Billy Joe MacAllister are tempted to fly something beneath the Tallahatchie Bridge in possible violation of questionable regulatory interpretations, then don’t mention it in your logbook. Post it on Facebook like everyone else because anything there is fiction and exempt from public scrutiny. If confused about the legitimacy of your intended deviation, invoke this legal precedent established in Sollozzo v. Corleone: If no one saw you do it, then it’s like it never happened … unless you put it in your logbook. Defense rests.

And to the Nobel Committee, I ask: How many more ABBA records must I purchase before Bootleg Skies, a potboiler chock-a-block with “periphery and the specificity of human experience,” gets the call? I’ll wait by the phone.