Getting Decent Aircraft Maintenance

On average, light planes today are in the worst mechanical state ever. But your aircraft needn’t be so if you are maintenance-aware and maintenance-involved.

I'm not a licensed A& P mechanic, but I play one on TV. Actually, I'm just a maintenance-involved owner who spends quite a bit of time hanging around the shop swinging wrenches on my Cessna 310, and I get to see a lot of other airplanes coming through the shop. I've concluded that most light planes are rather poorly maintained, and many are in a truly shocking state of disrepair.

I'm not a licensed A& P mechanic, but I play one on TV. Actually, I'm just a maintenance-involved owner who spends quite a bit of time hanging around the shop swinging wrenches on my Cessna 310, and I get to see a lot of other airplanes coming through the shop. I've concluded that most light planes are rather poorly maintained, and many are in a truly shocking state of disrepair.

I recall a pretty Cessna 182 that flew to the shop from Santa Barbara for an annual inspection not long ago. The owner, a retired gentleman, had obviously lavished a lot of money on his pride and joy. The paint was nice, the interior was recently re-done, and the panel sported a fine stack of Bendix/King avionics. But upon opening up the airframe, the mechanic noticed quite a bit of corrosion on the inboard section of both rear wing spars, and decided to take a closer look.

Careful flashlight-and-mirror inspection of hard-to-see areas between the inspection openings revealed sections of the rear spar that had corroded so badly that they were actually falling apart—a particularly severe condition that A& Ps call "exfoliation". Opening up the cabin headliner revealed that the wing carry-through structure was suffering from the same condition. To repair this corrosion damage would have cost a minimum of $20,000—more than the airplane was worth.

An FAA inspector was called to have a look, and he decided the corrosion was so bad that he refused to issue a ferry permit. The brokenhearted owner was told his best bet was to dismantle the airplane for parts. The radios, instruments, engine and prop were worth something, but the Skylane would never fly again.

The saddest part of this story is that corrosion of this magnitude doesn't occur in one year...or even two or three. This aircraft must have had a corrosion problem for many years. Had the owner been told of the corrosion problem five years earlier, and had he promptly placed his aircraft on an inexpensive corrosion-control program, that Skylane would still be airworthy today and for years to come. Why was the owner never told?

Then there was the retractable single that landed at our airport and ground-looped into the grass. Turned out that his left main gear wheel disintegrated on touchdown. His aircraft was equipped with three-piece magnesium-hub wheels—a variety that has a chronic history of cracking and failing. A service bulletin calls for inspecting such wheel hubs annually with dye-penetrant and, if cracked, replacing the wheel with a much-improved two-piece aluminum wheel that virtually never cracks. The magnesium wheels are so bad that most of them flunk the dye-penetrant test. Once again, it generally takes quite a long time for hub cracks to grow to the point that a wheel explodes. So why weren't the wheels on this Cardinal inspected and replaced years before one finally came apart on landing?

A young attorney from L.A. brought in his fancy late-model pressurized twin for an annual. Upon uncowling the left engine, the mechanic saw extensive exhaust stains, and discovered a major exhaust leak that had torched the aluminum engine support structure in the rear portion of the nacelle. Had the problem not been discovered when it was, an in-flight fire would have been a real possibility. As it was, the resultant exhaust system and structural repairs set the owner back several thousand dollars and downed the airplane for weeks. How was it possible that an exhaust leak of this magnitude wasn't discovered much earlier...during any of the last several 50-hour oil changes or even during a preflight inspection? The repair would have been a whole lot cheaper had the leak been noticed a little earlier.

Another cabin-class twin driver landed at our airport and discovered that he had no brakes at all on one side. Fortunately, our airport has a 6300'x150' runway, so the pilot was able to get his airplane stopped without departing the pavement. Although the airplane had recently been annualled, our shop found that the brake disks were severely worn—so far beyond limits that, upon brake application, the brake pucks actually popped out of the caliper and dumped all the brake fluid overboard! Brake disks are supposed to be micrometer-checked at each annual, and replaced when they reach a specific minimum thickness set forth in the service manual. Obviously, it must have been many years since the disks on this airplane had been miked.

Let me assure you that these are not isolated horror stories. Every week or so, I see another aircraft come into the shop suffering from similarly inexcusable neglect. In writing this article, I had a hard time choosing just these four. Based on my direct observations over the past five years, I have come to the conclusion that the majority of piston-powered airplanes are in a miserable mechanical state. The question is: why?

Brutal Economics

Part of the problem is simple economics. I bought my 1979 Cessna 310 seven years ago for about $80,000 with high-time engines and original paint. Today, after a double major overhaul, new paint and interior, and an appearance on the cover of AOPA Pilot, I figure the airplane is worth maybe $125,000.

But if Cessna were still making the 310 today, a new one would sell for the better part of a million dollars. (Priced a new Beech Baron 58TC lately?) In budgeting maintenance for my airplane, I should be treating it as an $800,000 machine (gasp!), not a $100,000 machine. But realistically, how many of us do? And it's not hard to figure that an $800,000 airplane that is maintained on a $100,000 airplane's budget is soon going to fall into disrepair.

But this is only part of the problem. Even airplanes owned by affluent folks who spare no expense are not immune from inadequate maintenance. I've seen plenty of maintenance horror stories on fancy birds with Victor Black-Edition engines and Bose headsets for all the passenger seats. And these owners are always particularly shocked, because they believed they were maintaining their aircraft to the highest standards on a money-is-no-object basis.

To fully understand how this comes about, you need to climb inside the head of your A& P mechanic for a few moments.

The Job Your A& P Hates Most

For the most part, A& Ps really enjoy their jobs. They like working on airplanes. They don't even mind the dirty tasks like greasing zerks, packing wheel bearings, or rebuilding oleo struts. Even a nasty job like changing a fuel bladder won't elicit more than a jocular wince out of most professional aircraft mechanics.

But there's one task that every A& P mechanic hates worse than any other part of his job: arguing with a customer about amount on the invoice. Most mechanics are so gun-shy about this that they have developed an highly effective defense mechanism. Here's how it works:

When you bring your airplane in for an annual inspection, your mechanic starts with some pre-conceived dollar amount in his head that he estimates to be your threshold of economic pain. That amount might be $2,000 for a fixed-gear single, for example, or $6,000 for a turbocharged twin. Your mechanic figures that you'll pay the bill without argument if it doesn't exceed this figure.

As he progresses through the inspection and starts writing down squawks on the discrepancy sheet, he is actually running an adding machine tape in his head, estimating what all of this is going to cost you. When the subtotal starts to approach his estimate of your threshold of pain, he may subconsciously start to look a little less hard. Or when he finds a marginal item, he may elect to defer action.

He might spot some minor corrosion but decide not to go looking for trouble. He might see an exhaust leak and decide it should be "monitored" rather than fixed on the spot. Or he might micrometer the brake disks, find them right at minimum limits (technically airworthy), and decide to write them up as "re-check at next inspection" rather than change them now.

Mind you, if it were his airplane, he'd have fixed these things immediately rather than letting them go. Or if you had been standing there during the inspection, he'd probably have pointed out the problems to you and asked you to decide whether to fix them now or let them go until next time. And you'd probably have said "let's fix them now."

But it wasn't his airplane and you weren't standing there. And the mechanic is thinking: "If I fix all this stuff now, I just know the customer is going to go ballistic when he gets the bill!" So he decides to let some stuff slip "until next time".

Of course, he might not remember this stuff by the time "next time" rolls around. Or you might be using a different mechanic or a different shop and they might not spot the problem. Or the new mechanic might spot the problem but decide to defer fixing it (using the same reasoning as the old mechanic did). As a result, deferred maintenance items often get overlooked or re-deferred until they deteriorate to the point of becoming critical, costly, or worse.

When your mechanic elects to defer a maintenance item on your airplane, he does so with the best of intentions. He rationalizes his action by telling himself that he is doing you a favor by keeping your maintenance bill below your threshold of pain (or what he believes that threshold to be). But believe me, he's not doing you a favor. It always costs more to fix a problem later than it does to fix it now. Often much, much more.

Once you understand how the system works, it's easy for you to ensure that your aircraft is maintained the way it should be. How? By becoming more maintenance-involved, and making the "defer or fix now" decisions yourself. There are several alternative strategies you can use.

The Owner-Assisted Annual

If you are even mildly mechanically-inclined and can manage to take a few days off from your regular job, consider participating in an owner-assisted annual. This is absolutely the best possible way to find out what mechanical shape your aircraft is really in, to ensure your aircraft receives the kind of maintenance you want, and to get a fascinating education that will make you a far better aircraft owner and pilot.

In an owner-assisted annual, you get to perform most of the time-consuming-but-routine work of opening up the airplane for inspection (removing inspection plates, fairings, seats, carpets, floorboards, etc.). Then you look over the shoulder of the A& P/IA as he inspects the aircraft and records any discrepancies he finds. At this stage, you have the opportunity to discuss each discrepancy with the mechanic, assess its airworthiness impact and cost to repair, and participate in the critical decision whether to repair it now or defer it for later. Having decided what to fix now, you and your A& P may decide to divide up the tasks: you can fix the simple discrepancies while he goes to work on the more difficult ones. Finally, when the squawks have all been dealt with, you get to close up the airplane while your IA prepares the maintenance logbook entries and makes the required sign-offs to return your aircraft to service.

I am firmly convinced that every aircraft owner owes it to himself to go through such an owner-assisted annual at least once. It's a lot of work (you'll discover muscles you never knew you had), but it's also a fantastic education that you simply cannot acquire any other way. And when the annual is done, you might be surprised to find that you really enjoyed it, and want to do it again next year.

That's what happened to me when I did my first owner-assisted annual six years ago. I've done it every year since. Sometimes it's difficult to take the time away from work, but I always do. As someone who spends most of his normal working day at a computer keyboard or on the telephone, I find swinging wrenches on my airplane to be a wonderful change-of-pace from my normal routine, and a very therapeutic to my psyche. And the rest of the year, I am secure in the knowledge that my airplane has been maintained to the highest possible standard, with no compromises.

If you participate in an owner-assisted annual year after year, you'll find that every year you are competent to perform more and more of the work yourself, and that your A& P needs to do less and less. After six years of owner-involvement in the maintenance of my T310, I'm now doing about 90% of the maintenance myself (including virtually 100% of the routine maintenance between annuals) and leaving only about 10% to my A& P. These days, my annual maintenance budget is only a third of what it used to be...not counting the value of my sweat-equity, of course.

Warning: Don't expect to save money by doing owner-assisted annuals...at least the first few times. It always takes your mechanic longer to teach you how to perform a task and to double-check your work than it would take for him to do the task himself. Your first one or two owner-assisted annuals are likely to be more expensive than usual because you'll find yourself deciding to fix many marginal discrepancies that your mechanic ordinarily would have deferred in your absence. I assure you that the education you receive is well worth this tuition, and that you'll be money ahead in the long run.

Other Strategies for Owner-Involved Maintenance

Even if you consider yourself a mechanical klutz, or if you can't possibly take time off work for an owner-assisted annual, you can still get more involved in the maintenance of your aircraft. One good way is to be present on-site for the actual "inspection" portion of your annual. Simply arrange with your A& P that you be notified when your aircraft has been completely opened up, and request that he not start the inspection until you arrive at the shop. The inspection portion of an annual will normally take between 4 and 8 hours to complete, so you'll only lose one day of work. You'll have the opportunity to see all the discrepancies with your own eyes, to discuss the costs, and to participate in the fix-or-defer decisions with your mechanic. In almost every case, your presence will result in more decisions to fix and fewer to defer maintenance than what would have occurred in your absence. And you'll know exactly where your aircraft stands, maintenance wise.

I'd urge you to "make the time" so that you can be present for the inspection part of your annual. But if you simply can't, there's another option. Ask your A& P to do the inspection, FAX you the discrepancy sheets, and then have a telephone conference during which you walk through the discrepancies with him, discussing cost-to-fix for each item, and making fix-or-defer decisions together on the phone. This approach is much less desirable because you don't get a chance to see the problems with your own eyes, but it is far superior to the usual "here's the airplane, call me when it's ready" scenario.

Trend-Monitoring and Troubleshooting

As a maintenance-involved owner, you need to take responsibility for trend-monitoring between annuals. As the principal pilot of your aircraft, you know what is "normal" for your aircraft far better than your mechanic does. Be vigilant for anything that changes unexpectedly and bring it to your mechanic's attention right away. Changes always happen for a reason. Even the most trivial or innocuous changes can be clues to possibly-serious mechanical problems, so act upon them right away. (See sidebar for an example.)

Another important way for you to become more maintenance-involved is to take a more active role in the troubleshooting process. Before you hand over your aircraft keys to your mechanic with instructions to fix some squawk, make certain that you've done everything you possibly can to isolate the problem, and that you've given your mechanic every possible clue for determining the cause.

For example, if you tell your mechanic that your alternator is tripping off-line with an over-voltage annunciator, he's not sure where to start. Better to do some homework first and give him a detailed evaluation:

"The alternator is tripping off-line with an over-voltage light. I first noticed this problem 18 months ago, but it didn't recur for 3 months. Lately, it has been happening more and more frequently. The over-voltage trip almost always seems to occur when I extend the landing gear. I hooked my Radio Shack digital multimeter to the cigarette lighter socket and monitored bus voltage during several flights. With the engine running at 1000 RPM or more, bus voltage appeared to remain consistently between 27.5 and 28.5 volts under widely varying electrical loads. Consequently, I believe that the alternator and regulator are probably working okay. I suspect the over-voltage relay may be bad."

Airframe Inspection: Annual, 100-Hour, or Progressive?

Some conscientious aircraft owners believe that the key to good maintenance is frequent inspections. They think that if annual inspections are good, several 100-hour inspections per year must be even better. They brag that they voluntarily maintain their aircraft to Part 135 standards, even though they use it strictly for Part 91 operations.

When I bought my first airplane 25 years ago, I believed the same thing. But during the past six years of hanging around the shop and seeing how aircraft maintenance is done up close and personal, I have concluded that this belief is misguided. In my opinion, one really thorough annual inspection a year is the best option for most owner-flown airplanes.

One reason for this is that each time the airframe is opened up for inspection, a certain amount of unavoidable wear-and-tear is incurred. Paint is chipped, nutplates are stripped, tubing and wire bundles are flexed, gaskets are disturbed, and so forth. In the process of inspecting for problems, certain additional problems are inevitably created.

Another consideration is that it usually takes a good deal longer to open and re-close the aircraft than it does to perform the actual inspection. By limiting airframe inspections to one per year, one can justify taking the time required to do a truly meticulous inspection that leaves no stone unturned. If the airframe is inspected every 100 hours, the inspections tend to be much more cursory...the mechanic often rationalizes that "I looked at that 100 hours ago, I don't need to look at it this time" or that "I won't bother to open that now, I'll catch it at the next 100-hour."

But the biggest problem with 100-hour inspections, in my judgment, is that the temptation to defer maintenance is greatly increased. It is far easier for your A& P to rationalize letting a discrepancy go rather than fixing it if he knows the aircraft will be inspected again in 100 hours; he's less likely to defer the same item if he knows the aircraft may not be back in for maintenance for a full year.

FAA-approved progressive inspection programs are available for many aircraft, as an alternative to the normal annual and 100-hour inspections. A typical progressive inspection program consists of four phased inspections to be performed at 50-hour intervals. For a Part 135 aircraft that is flown at least 200 hours per year, a progressive program can be advantageous in reducing both downtime and the frequency of superfluous airframe opening/closing cycles. But for owner-flown aircraft, progressive inspections hold the same pitfalls as 100-hour inspections: an increased temptation to defer maintenance.

Furthermore, both 100-hour and progressive inspections tend to discourage owner-involved maintenance. An owner like me may be willing to take a day or a week off from work once a year to participate in the maintenance of his aircraft, but he's far less likely to do so two or three or four times a year. So from my perspective, doing one really thorough annual inspection per year is the best strategy for most owner-flown aircraft.

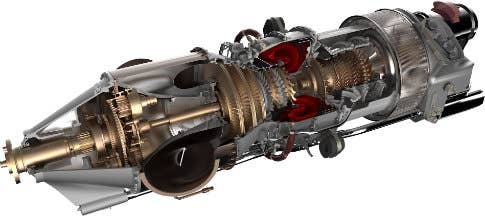

Powerplant Inspection

But there is one aspect of aircraft maintenance where I believe "more is better", and that is in the engine compartment from the firewall forward. While airframe problems tend to occur infrequently and deteriorate slowly, powerplant problems are quite the opposite. Every time you fly your airplane, the engine is doing its best to shake, bake, burn, and rub itself and everything in its immediate vicinity to death. Minor leaks of exhaust, fuel, or oil can get worse with frightening rapidity, and can result in serious safety-of-flight problems. And even if powerplant-related problems are caught before they progress to the life-threatening stage, they are likely to be devastatingly expensive to repair.

Consequently, I believe that it is impossible to inspect the engine compartment too often. At the very minimum, the engine should be de-cowled every 25 hours and given a very thorough visual inspection for signs of exhaust leaks, oil or fuel leaks, chafing, burning, loose fasteners, cooling baffle deterioration, and so forth. If you change oil every 50 hours like I do, you need to plan engine compartment inspections between oil changes.

Ideally, you should inspect the engine carefully every few flights. If you fly a Bonanza or a twin Cessna with easy-open hinged cowl doors, you're lucky in this regard. If you fly a Cessna single or an Aztec that has minimal pre-flight access to the engine compartment, you need to discipline yourself (or ask your mechanic) to pull the cowling at frequent intervals and take a close look.

Most importantly, always fix any firewall-forward problem immediately, no matter how small. Leaks, cracks, and chafes in the engine compartment usually get worse (and costly) fast. A tiny leak at an exhaust port, for example, might require just an hour of labor and a two dollar exhaust gasket to fix now. Let it go until the next oil change, and it might require replacing the exhaust riser and sending out the cylinder to have the flange machined flat...and set you back a thousand bucks plus ten days of unscheduled downtime. Let it go until the next annual, and you might have an in-flight fire.

Choosing a Shop

Every aircraft owner has his own set of criteria for choosing where to have his aircraft maintained. Some are impressed if the shop floor is clean or if the service manager wears a tie. Others are attracted to low prices (and some to high prices!). Many owners based at smaller airports feel that they have no choice because there is only one shop on their field. I would like to suggest that you add two more criteria to your list:

Pick a shop that encourages owner-assisted annuals and maintenance-involved owners. Walk away from a shop that resists your desire to participate in detailed maintenance decisions about your aircraft. Run away from a shop that prohibits customers from entering the shop floor (usually "for insurance reasons").

Pick a shop that has more than one IA...that's an A&P mechanic who has qualified for an FAA "Inspection Authorization". Only an IA is authorized to perform the actual inspection portion of an annual and to sign your aircraft off for return to service. (Any old A& P can open, close, fix squawks, and sign off 50- and 100-hour inspections.) Even the best IA won't catch every maintenance discrepancy. In a shop with multiple IAs, you will probably have more than one pair of eyes looking at your aircraft, and the chance of overlooking an incipient problem is reduced. The shop I use has seven A&Ps on staff, six of whom are IAs—but most shops have only one IA or occasionally two.