Nosewheel Shimmy: McFarlane, Lord Fixes

The typical stock nosewheel shimmy dampener does a decent job of taming minor oscillations, but the nosewheel on older airplanes (and Cessna singles in particular) eventually needs some care. When…

The McFarlane nosewheel shimmy damper on a Cessna single.

The typical stock nosewheel shimmy dampener does a decent job of taming minor oscillations, but the nosewheel on older airplanes (and Cessna singles in particular) eventually needs some care. When all other components are healthy, that often means replacing the shimmy damper (this is occasionally called a dampener), and two popular aftermarket upgrades come from McFarlane and Lord.

Here’s a look at what is typically involved.

Shake, Rattle, Roll

In simple terms, shimmy is a reaction to inputs that are compounded by speed, surface, wear on parts and to some degree a number of other variables. It’s instantaneous directional changes to the tire on the nose (or tail), through the wheel and axle, caused by wear in critical components and force dynamics on the tire. Shimmy is inherent in any landing gear design that depends on close tolerances, attention to maintenance and a particular geometry.

Nosewheel shimmy comes on fast. You are going straight and smooth, and then suddenly you are shaking like all get out. Some airplanes with free castering nosewheels like on a Grumman or Cirrus, to name two, use Belleville washers (or disc springs)—cone-style washers that compress and apply friction on the nose strut axle bearing.

Cessna realized a problem with its nosegear when it glommed what looked like a Scott tailwheel onto a pipe on the front of a model 120. Cessna quickly developed the damper, and photos of a 1959 model 150 show a shimmy damper installed to fix the problem. This is a piston with a fixed orifice, and hydraulic fluid is shunted to either side of the piston by the axial forces, dampening the movement almost instantaneously.

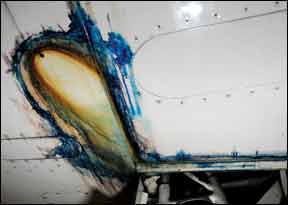

Cessna’s damper works well; however, over time it wears out and components have to be replaced. McFarlane Aviation’s testing revealed that a Cessna damper generally fails at 17,000 cycles and requires overhaul. The shaft, McFarlane realized, is too thin and will bend under loads from excessive speed or braking, and the component developed spots (called galling) on the shaft. This changes the cross section of the rod, and the interior bore of the cylinder walls will develop long scratches and gouges from the edges of the piston. The hydraulic fluid will not compress, so it finds a way out of the cylinder under temperature changes, usually around worn O-rings. Eventually, most of the parts will be worn out and need replacing—more often when overlooked during regular maintenance or under extreme operating conditions.

The stock Cessna damper is rather small and does not require much H5606 fluid. This means that any fluid loss is a major percentage of the total. Some techs I talked with report putting in a few drops every few hours. Adding more fluid than this? It’s likely time for a rebuild. The problem here is that the internal parts are quite costly. The pushrod alone is $900, according to the ones I sourced. This is can be more than the entire McFarlane assembly. While the O-ring kits are only a few bucks, the rods are often bent or worn out and simply require replacement.

At this point, the option is to rebuild the Cessna damper, or replace it with an aftermarket kit from Lord or McFarlane. Rebuilding the part is not difficult, and requires a couple of tools and a clean work environment. Aftermarket parts make the job doable, thanks to McFarlane’s hundreds of PMA Cessna replacement parts. Still, the older the part gets, the more parts and maintenance it will require. The typical McFarlane damper can be rebuilt in about an hour and a half. The only specialized tool needed is a spring installation tool, available with the kit or standalone.

Lord Dampers

The Lord dampeners (www.lord.com) are cylinders with a rod and fully bonded elastomeric material, and what’s unique is it doesn’t use fluid. The piston is really a rubberish compound that applies constant pressure against the cylinder wall. A long-lasting and proprietary lubricant allows controlled slippage that resists forces in both directions. There is increased friction when the piston changes direction, providing more intense dampening; however, this lessens almost immediately. The company certainly has a lot of experience using rubber for dampening vibration (it makes engine mounts), but the problem is that even this long-lasting part provides variable resistance to steering as it resists movement in both directions.

The Lord dampener does have an impressively long service life, estimated at 10 years or more under regular use, and could surpass 300,000 cycles (proven before failing under accelerated testing). When it does wear out it is non-serviceable and cannot be rebuilt; you have to replace it.

Some basic Lord dampeners do come in well under the Cessna price, but others are as high as $2700. For 20 years, the Lord damper was the only aftermarket option and was sold at prices competitive with a Cessna replacement. The Lord damper is well regarded and proven, even though some might attest to feeling a bit of stiffness during the nosewheel steering.

McFarlane Dampeners

When designing the McFarlane aftermarket dampener, Dave McFarlane and Ben Maples decided to re-create and improve the Cessna part by identifying its problems and redesigning it. They included things like a quad-ring seal, temperature- and altitude-compensating fluid orifices, a larger diameter piston rod and a new design that allows the fluid level to be checked without removing the component from the nosewheel. In its design, every weak area of the Cessna damper was addressed.

McFarlane developed its shimmy damper using a quad-ring technology, or an O-ring that has four sides, more surface area and does not spin or twist inside the cylinder. The company’s original prototype proved to them that the unit could undergo thousands of cycles (300,000-plus) without needing servicing, plus the dynamic tests revealed that the dampening started virtually immediately when a force is applied to the nosegear. The company makes all of the test specs available on its website at the end of their shimmy damper product page—it’s worth a read.

Benefits they had not expected included the absence of leaks throughout the test period, the lack of servicing needed for the fluid and the longevity of the part, even under accelerated testing protocols. Using hydraulics, the response on the ground feels immediate to the pilot; in fact, you have to be looking for any forces to realize they aren’t there—it’s that much of an improvement over the OEM. Visit www.mcfarlaneaviation.com.

Better Than Original

I can easily recommend both the Lord and McFarlane dampeners, based on quality and value. In my view, McFarlane’s damper puts a sharp focus on improving OEM designs, and the resulting longevity and less required maintenance could give it the edge. Plus it can be rebuilt. Still, make any dampener last longer by reducing loads on the nosewheel. While taxiing on rough surfaces, make it a habit of holding the elevator aft when possible.

McFarlane has made a successful business of supplying certified (FAA-PMA) parts for Cessna and Piper applications, and I think many are better than the OEM’s. It focuses on ridding the weaknesses by using modern materials, better technology and more advanced testing. When it comes to the abuse put on nosewheel shimmy dampeners, that’s a good thing.

This article originally appeared in the August 2021 issue of Aviation Consumer magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to Aviation Consumer!