The Making of Air Force One

Remember the 1997 motion picture starring Harrison Ford as prez, Glenn Close as veep, and Gary Oldman as the terrorist/hijacker bad guy? Sort of a “Die Hard” derivative set aboard the presidential 747? George C. Larson of Air & Space/Smithsonian magazine takes us behind the scenes and explains the extraordinary airmanship, mind-boggling logistics, and fascinating special effects involved in the creation of this movie. Of course you realize nothing like this could ever happen. Or could it?

Here's the concept: Some terrorists have a gripe with the UnitedStates. Terrorists are in the business of hijacking airliners, and as any terrorist worthhis Semtex knows, there is one airliner without equal: Air Force One. And as long as youare going to hijack Air Force One, you may as well do it while the president and the firstfamily are aboard.

Here's the concept: Some terrorists have a gripe with the UnitedStates. Terrorists are in the business of hijacking airliners, and as any terrorist worthhis Semtex knows, there is one airliner without equal: Air Force One. And as long as youare going to hijack Air Force One, you may as well do it while the president and the firstfamily are aboard.

In the action movie Air Force One, Harrison Ford is castas the president of the United States and Glenn Close as the vice president, but thesurprise star of this movie may well turn out to be an airplane: the Boeing 747-146 thatplays the part of Air Force One, one of two modified 747-200s operated by the89th Airlift Wing at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland. To create a kind of stunt doublefor the presidential aircraft, the producers of Air Force One rented a standardproduction 747 from American International Airways, a charter cargo carrier based inYpsilanti, Michigan, and founded by former drag-racing champion Conrad "Connie"Kalitta. The Boeing wide body, registered in the United States as N703CK, was the 54thbuilt and the third to enter the Japan Air Lines fleet after it rolled off the productionline in June 1970. All the other military aircraft in the film appear as themselves, withthe services' costs paid for by Columbia Tristar Pictures.

The director of Air Force One is Wolfgang Petersen, whosefilm Das Boot, a gritty tale of life aboard a World War II German submarine, establishedhis penchant for exhaustive research and painstaking accuracy.

The director of Air Force One is Wolfgang Petersen, whosefilm Das Boot, a gritty tale of life aboard a World War II German submarine, establishedhis penchant for exhaustive research and painstaking accuracy.

To get everything right, Petersen relied on researcher Brian McNulty, who recruitedexperts from the Secret Service and the military. McNulty also scheduled the militaryaircraft, a nail-biter of an experience: "I find it to be quite exciting when youorder up a dozen aircraft, and your first day of shooting is on a certain day at 1500hours, and I'm standing there on the tarmac, and at 1500 hours they start to rollin." McNulty acknowledges that there's a price for such a high level of cooperation.The Air Force got script approval and the assurance of a positive depiction of the serviceand its people.

To obtain seamless realism in the flying scenes, which combine actual flying with shotsof models as well as special effects created on computers, Petersen relied on McNulty'sexperts and David Paris, the man responsible for the planning and coordination of everyflying sequence. Paris, a helicopter pilot who learned his craft during eight years in theBritish Royal Navy, has an eclectic roster of motion pictures to his credit, from Ishtarto Mission Impossible.

To obtain seamless realism in the flying scenes, which combine actual flying with shotsof models as well as special effects created on computers, Petersen relied on McNulty'sexperts and David Paris, the man responsible for the planning and coordination of everyflying sequence. Paris, a helicopter pilot who learned his craft during eight years in theBritish Royal Navy, has an eclectic roster of motion pictures to his credit, from Ishtarto Mission Impossible.

Piloting the 747 was Paul Bishop, an AIA captain with more than 25,000 hours, 4,000 ofthem in 747s. The film involved two primary flying sequences, one shot near the ChannelIslands off the California coast and another at Rickenbacker International Airport nearColumbus, Ohio. In the latter sequence, Paris had to have the big Boeing veer off therunway, out of control, then take off and barely clear a parked C-141 transport. In thestory, the crew members lock themselves into the flight deck after hearing gunfire aboard.They plan to deviate to Ramstein Air Base in Germany, where special ground units can stormthe airplane and overwhelm the terrorists.

While the AIA 747 was off getting a $300,000 paint job to replicatethe Air Force One color scheme, Paul Bishop was busy at meetings to map out how thesequence would be shot. "David [Paris] had a storyboard, like a comic book, whereeach scene is drawn out," Bishop recalls. To shoot the portion in which the 747 goesout of control and veers 45 degrees off the runway toward a near-collision, cameramanDavid Nowell planned to reduce the risk by using a time-honored trick and slow the cameradown to half speed: 12 frames per second. "The sequence begins with us [stopped] onthe runway, then we accelerate to pass camera center at 60 knots," Bishop says.

While the AIA 747 was off getting a $300,000 paint job to replicatethe Air Force One color scheme, Paul Bishop was busy at meetings to map out how thesequence would be shot. "David [Paris] had a storyboard, like a comic book, whereeach scene is drawn out," Bishop recalls. To shoot the portion in which the 747 goesout of control and veers 45 degrees off the runway toward a near-collision, cameramanDavid Nowell planned to reduce the risk by using a time-honored trick and slow the cameradown to half speed: 12 frames per second. "The sequence begins with us [stopped] onthe runway, then we accelerate to pass camera center at 60 knots," Bishop says.

The film crew prepared for the shoot by using the aircraft performance manuals tocalculate the acceleration and braking distances for the 747's weight and the air densityat the airport to establish a maximum speed. Then Bishop assigned flight engineer HarveySigmon to observe the speed readout on the inertial navigation system while he and copilotRobert Earl "Jet Man" Jeter handled the power and the steering. When the finaltakes were projected at the normal 24 frames per second, the 60 knots looked like aspeedier 120.

Bishop repeated this and other action sequences through 10 takesand 60 hours on the 747's clock, which were stretched over many days by the limits ofmoviemaking and of the airplane itself. The landing at Ramstein is supposed to take placeat night, but in order to get the light they wanted the camera crews could shoot onlywithin a 15-minute window after sunset or before sunrise. And, like any star, the 747 hadits own special needs. The 16 sets of brakes (only the nosewheels are not braked) have tobe cooled down after each run. And it wouldn't have been moviemaking without the glitches:In one instance a "doghouse" sheltering a ground-level camera was blown over bythe jet blast from the number two engine; the moviemakers rebuilt it and anchored itsecurely. Then early one morning, with a front moving in and ground traffic sending thecrew on long detours around the taxiways of Rickenbacker, they rolled the dice to performa final take. And the gamble came up snake eyes.

Bishop repeated this and other action sequences through 10 takesand 60 hours on the 747's clock, which were stretched over many days by the limits ofmoviemaking and of the airplane itself. The landing at Ramstein is supposed to take placeat night, but in order to get the light they wanted the camera crews could shoot onlywithin a 15-minute window after sunset or before sunrise. And, like any star, the 747 hadits own special needs. The 16 sets of brakes (only the nosewheels are not braked) have tobe cooled down after each run. And it wouldn't have been moviemaking without the glitches:In one instance a "doghouse" sheltering a ground-level camera was blown over bythe jet blast from the number two engine; the moviemakers rebuilt it and anchored itsecurely. Then early one morning, with a front moving in and ground traffic sending thecrew on long detours around the taxiways of Rickenbacker, they rolled the dice to performa final take. And the gamble came up snake eyes.

"We 'thermalled' the tires," Bishop says, "and the boss was not happywith that." What happened was actually a built-in safeguard doing its job: To preventexplosive failure of the tires and rims from heat buildup, the braked wheels on the 747have metallic plugs that melt on overheating to release all the air in the tire. Eventaxiing creates tire heat, and the 747-146 is limited to slightly less than seven miles onthe roll before it has to stop and cool its wheels. Somehow, in the course of braking hardand taxiing back for another take, the tires had built up enough heat to melt the plugs."It happened at 6 a.m., and by 6 p.m. it was ready [to fly again]," Bishop says,crediting his crew for the rapid turnaround.

The shoot planned for the area near California's Channel Islandsinvolved a sequence wherein commandos extend a line from a Fulton Winch (see "QueasyRider," Aug./Sept. 1996) mounted in an MC-130 Combat Talon to an entry hatch on AirForce One. The commandos are supposed to slide down the line to get aboard the airplane,then reverse the process to get off.

The shoot planned for the area near California's Channel Islandsinvolved a sequence wherein commandos extend a line from a Fulton Winch (see "QueasyRider," Aug./Sept. 1996) mounted in an MC-130 Combat Talon to an entry hatch on AirForce One. The commandos are supposed to slide down the line to get aboard the airplane,then reverse the process to get off.

This time, weather was the problem. To establish that the airplanes are over the oceanduring this sequence, the cameras needed a view of the water. "What we got was crudfrom 4,000 feet down to sea level," Bishop says. "And it was persistent. We wereout there for almost two weeks...and we would take off every morning two hours beforesunrise and look for a hole until the envelope for filming expired."

Eventually, they got a break in the weather that enabled them tojoin up with the MC-130 and with the modified North American B-25 Mitchell camera plane.Flying at about 200 mph, well below the 747's speed when it is slowing to approach anairport, Bishop flew with the flaps extended 10 degrees throughout the sequence. Theformation join-up involving three "dissimilar airplanes," as Bishop understatesthe problem, was ticklish. The 747 cruises at more than 600 mph, C-130s are comfy at 350mph, and on a good day, the B-25 can handle maybe 230, tops.

Eventually, they got a break in the weather that enabled them tojoin up with the MC-130 and with the modified North American B-25 Mitchell camera plane.Flying at about 200 mph, well below the 747's speed when it is slowing to approach anairport, Bishop flew with the flaps extended 10 degrees throughout the sequence. Theformation join-up involving three "dissimilar airplanes," as Bishop understatesthe problem, was ticklish. The 747 cruises at more than 600 mph, C-130s are comfy at 350mph, and on a good day, the B-25 can handle maybe 230, tops.

The MC-130 flew with a cable trailing behind it; the special effects wizards completedthe linkup by connecting the cable end to the 747 with their computers. "They alsoadd the people," Bishop says, though there was one exception when the moviemakerstried to put a human figure on the cable. "They did trail a dummy—they called himFelix, dressed in a suit and tie, out of the Talon. But [the 747's] bow wave was movinghim around, and first his tie comes off, and then his coat comes off, and I'm hoping itdoesn't enter our number two engine." They decided to ditch Felix.

Bishop had to fly in tight formation with theturboprop MC-130, responding to direction from the camera crew aboard the B-25. Using handsignals, they told him how they wanted him to adjust his position. Bishop established avisual reference somewhere on the MC-130, sometimes lining up a wingtip light with a spoton the smaller airplane's fuselage or lining up one of its antennas with a spot on his ownwindshield. Throughout this series, Bishop's cockpit was only a few feet away from theTalon's wingtip, and the other aircraft's tail was about the same distance from his numbertwo engine on the 747's left wing. "I never thought I'd reach the age of 57 and havean experience like this," he says.

Bishop had to fly in tight formation with theturboprop MC-130, responding to direction from the camera crew aboard the B-25. Using handsignals, they told him how they wanted him to adjust his position. Bishop established avisual reference somewhere on the MC-130, sometimes lining up a wingtip light with a spoton the smaller airplane's fuselage or lining up one of its antennas with a spot on his ownwindshield. Throughout this series, Bishop's cockpit was only a few feet away from theTalon's wingtip, and the other aircraft's tail was about the same distance from his numbertwo engine on the 747's left wing. "I never thought I'd reach the age of 57 and havean experience like this," he says.

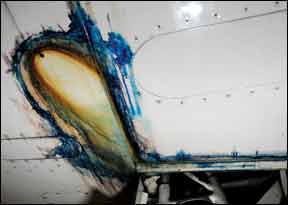

Although the 747 featured in Air Force One lacks the bulgein the nose for aerial refueling equipment and a few of the antennas found on the fuselageof the real Air Force One, the accuracy of its paint and studio-supplied decal markingsfooled a lot of people on the ramp at Los Angeles International Airport, who believed thepresident was in town. The ensuing uproar was easy to allay compared to the excitement ofthe young fliers aboard a pair of F/A-18s who were scrambled to intercept some unexplainedradar targets. "They came up and saw what looked like Air Force One full of bulletholes [simulated by decals]," Bishop recalls. "Once they ID'ed it, [Los AngelesCenter] told them who we were and they broke off and went home. But I can just imaginewhat was going through their minds," Bishop says, chuckling.

Although the 747 featured in Air Force One lacks the bulgein the nose for aerial refueling equipment and a few of the antennas found on the fuselageof the real Air Force One, the accuracy of its paint and studio-supplied decal markingsfooled a lot of people on the ramp at Los Angeles International Airport, who believed thepresident was in town. The ensuing uproar was easy to allay compared to the excitement ofthe young fliers aboard a pair of F/A-18s who were scrambled to intercept some unexplainedradar targets. "They came up and saw what looked like Air Force One full of bulletholes [simulated by decals]," Bishop recalls. "Once they ID'ed it, [Los AngelesCenter] told them who we were and they broke off and went home. But I can just imaginewhat was going through their minds," Bishop says, chuckling.

Whether real or replicated, Air Force One is more than just an airplane. "Whatattracted us to the project is the idea that Air Force One is the flying White House....[As a symbol] it's as if the president is bringing the crown jewels," says McNulty.Air Force One has long embodied presidential prestige and global influence. Now, withHollywood's help, add action-movie star power to that list.

Originally published in Air & Space/Smithsonian, Aug./Sept. 1997. Copyright 1997, Smithsonian Institution.All rights reserved

The Real Air Force One

Air Force One is a Boeing 747-200B aircraftthat was extensively modified to meet presidential requirements. The original paint schemewas designed at the request of President John F. Kennedy, who wanted the airplane toreflect the spirit of the national character. He also directed that the words "UnitedStates of America" appear prominently on the fuselage, and that the U.S. flag bepainted on the vertical stabilizer.

Boeing delivered two uniquely modified Boeing 747-200 Air Force One presidentialaircraft in 1990. The airplanes replaced the Boeing 707-320 airframe that had served thenation's chief executives for nearly 30 years.

U.S. presidents have flown on Boeing aircraft since 1943, when President Franklin D.Roosevelt flew to Casablanca aboard a Boeing model 314 Clipper. In 1962, U.S. presidentswere provided modern jet transportation with the introduction of the Boeing model707-320B, which was to become known by the radio call sign used when the president isaboard: Air Force One. In all, seven presidents were served by the 707-320B.

Today, the chief executive flies aboard a modified 747-200B, the newest and largestpresidential airplane. The 747 is ideally suited to support the travel requirements of thepresident.

The Flying "Oval Office"

The 747s were built at the Boeing Everett, Wash., facility, thenflown to the company's Wichita, Kan., facility for configuration as Air Force One. Theaircraft were extensively modified to meet presidential requirements. The flying"Oval Office" has 4,000 square feet of interior floor space, which features aconference/dining room, quarters for the president and the first lady, and an office areafor senior staff members.

The 747s were built at the Boeing Everett, Wash., facility, thenflown to the company's Wichita, Kan., facility for configuration as Air Force One. Theaircraft were extensively modified to meet presidential requirements. The flying"Oval Office" has 4,000 square feet of interior floor space, which features aconference/dining room, quarters for the president and the first lady, and an office areafor senior staff members.

Another office can be converted into a medical facility when required. There are workand rest areas for the presidential staff, media representatives and Air Force crews; twogalleys are each capable of providing food for 50 people.

Lower lobes of the aircraft were modified to accommodate the airplane's self-containedair stairs and interior stairways that lead to the main deck. The lower lobes also featureunique storage to accommodate substantial amounts of food (up to 2,000 meals) andmission-related equipment. In addition, this area contains an automated self-containedcargo loader and additional electronics equipment.

About 238 miles of wire wind through the presidential carrier. This is more than twicethe wiring found in a typical 747. Wiring is shielded to protect it from electromagneticpulse, which is generated by a thermonuclear blast and interferes with electronic signals.

The airplane's mission communications system provides worldwide transmission andreception of normal and secure communications. The equipment includes 85 telephones, aswell as multi-frequency radios for air-to-air, air-to-ground and satellite communications.

Air Force One provides longer range for presidential travel and can be self-sufficientat airports around the world. Modified for aerial refueling, it has virtually unlimitedrange.

Up to 70 passengers and 23 crew members can be accommodated, including necessary groundcrew required to travel with the plane.

The 89th Military Airlift Wing at Andrew Air Force Base, Md., is responsible for AirForce One, which is housed in a 140,000-square-foot maintenance and support complex atAndrews Air Force Base.