The Savvy Aviator #30: The Mechanic’s Signature

It’s illegal to fly after maintenance until a mechanic signs a maintenance-record entry approving the aircraft for return to service. So what do you do if the mechanic says, “I can’t sign it off”?

Picture this: You're away from home base when your airplane develops a minor problem. You ask the local repair shop to fix it. After working on the problem for a few hours, the shop reports back that it will take much longer to fix than you anticipated, and cost a lot more than you were prepared to pay.You're not very happy about this, and decide you want to take your airplane to your regular mechanic back home. But the shop tells you, "Sorry, I can't sign off your airplane in this condition."Can they do that? What are your options?This is precisely the situation that the owner of a Cessna 340 found himself in recently when he had a problem with pressurization leaks. His regular mechanic didn't have the equipment necessary to pressurize the cabin on the ground in order to locate the leaks, so the owner decided to take the plane to a large, reputable FBO that does a lot of work on pressurized aircraft. The owner's plan was to have the big shop use their equipment to identify the leaks, then have his regular mechanic fix them. But things didn't work out exactly as planned, as the owner explained:

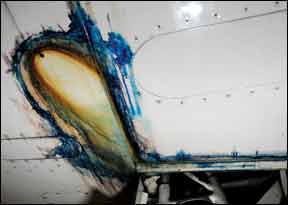

"I put my plane into Galvin Flying Service in Seattle to take a look at why I am only getting 3.1-psi pressure differential when I should be getting 4.2 psi. I authorized two to three hours of labor to pressurize the cabin, identify the leaks, and replace the door seal that had several visible cuts."Several days later, Galvin hit me with a bill for 40 hours of work to fix two leaks -- one of the forward pressure bulkhead and another in the wing root. They told me that they still had to do another 10 hours of work to replace the landing gear push-pull-tube boots."I am disappointed with Galvin, and told them I wanted them to stop work so I could take the plane back to my trusted mechanic. But the IA at Galvin told me that he couldn't sign off the aircraft because it isn't airworthy."What is the story here? Can he really withhold his signature? The airplane is safe to fly, and in fact the cabin altitude is pretty good up to FL220. Help!"

Can They Do That?

This owner's plight triggered a vigorous discussion that involved me and a number of other A&P/IA mechanics. All of us agreed the Galvin IA was acting improperly by withholding his signature from the maintenance logs. FAA regulations do not permit a mechanic to ground an aircraft or hold it hostage in this fashion.You might well be asking yourself how can this be? Doesn't a mechanic have the right to decide when he is or is not comfortable signing off a maintenance logbook entry approving an aircraft for return to service? Surely a mechanic is not compelled to sign off an aircraft that he doesn't consider airworthy. If mechanics didn't have such discretion, wouldn't their signatures become meaningless?Indeed, this is such a confusing issue that even A&Ps get confused about it (as clearly was the case with the IA at Galvin). Nevertheless, the answer is clear and unambiguous if you take the time to read and understand the relevant FAA regulations.

The Regs

The FAA regulations concerning maintenance appear in 14 CFR Part 43. Specifically, the rules governing maintenance records and sign-offs appear in 43.9 and 43.11. 43.9 deals with records of maintenance other than inspections, while 43.11 deals with records of inspections.It turns out that the rules for logging and signing off inspections are dramatically different than the rules for logging and signing off other maintenance work such as repairs, alterations, and preventive maintenance. In particular, the meaning of the mechanic's signature in the maintenance logbook is entirely different, and it's essential for both mechanics and aircraft owners to understand the difference clearly.

Signing Off Inspections

If an owner puts his aircraft in the shop for an FAA-mandated inspection (e.g., an annual or 100-hour inspection), then the rules of 43.11 apply. The inspecting mechanic is required to look at the entire aircraft from wingtip to wingtip and spinner to tailcone. He must verify that it meets all airworthiness requirements. He must verify that the aircraft complies with its type design, is in condition for safe operation and complies with all applicable airworthiness directives.The mechanic's signature in the logbook approving the aircraft for return to service after such an inspection attests (at least in theory) that every molecule of the aircraft is airworthy. This is an impossibly high standard, of course, and it's why it is often said that an IA "signs his life away" when he signs off an annual inspection and approves the aircraft for return to service.What if the inspection reveals some discrepancies that make the aircraft unairworthy, but the owner is unwilling to repair them? Can the inspecting mechanic simply refuse to sign the maintenance logs until the owner cries "uncle" and agrees to authorize the repairs?No, he can't. The FAA cleverly anticipated this possibility, and 43.11 provides guidance to the mechanic in this situation. It calls for the mechanic to "sign off the inspection with discrepancies" and to give a signed and dated list of discrepancies and unairworthy items to the aircraft owner.Once the inspecting mechanic has done this, the annual inspection is complete and the inspecting mechanic's job is finished. His signature disapproving the aircraft for return to service attests (at least in theory) that every molecule of the aircraft is airworthy except for those items he enumerated on the discrepancy list given to the owner. The aircraft cannot be flown legally until the owner corrects the discrepancies. The owner is free to hire any mechanic he wishes to correct them. There is no requirement for the owner to have the aircraft re-inspected for another 12 calendar months (or 100 hours or whatever).

Signing Off Repairs

But our Cessna 340 owner didn't authorize Galvin to do an annual or 100-hour inspection of his airplane. He simply asked them to locate the pressurization leaks and replace the door seal. Since he did not authorize an inspection, the rules of 43.9 apply.Under those rules, the mechanic is required to make a maintenance record entry that includes the date, aircraft time-in-service, a description of the work performed, the name of the person who did the work, and the signature and certificate number of the mechanic approving the work.But there's a big difference from 43.11. Quoting directly from 43.9:

"The signature constitutes the approval for return to service only for the work performed." (emphasis AVweb's)

In other words, the mechanic's sign-off of a repair, alteration, or preventive maintenance does not purport to attest that the aircraft is airworthy; it only attests that the work performed by the mechanic is airworthy. Thus, the only legitimate reason for a mechanic to withhold his signature after performing repairs, alterations or preventive maintenance would be if the work he did was unairworthy!Here's the example I use in my Savvy Owner Seminars to clarify this point: An owner puts his airplane in the shop to replace a flat-spotted, main-gear tire. When he comes back to pick up the aircraft, the new tire is on the aircraft but the mechanic says he can't sign off logbook because he discovered a big dent in the leading edge of the wing.Can the mechanic do that?No, he can't. The owner hired him strictly to change the tire. He was not hired to inspect the aircraft. His signature in the log does not imply that the wing is airworthy, only that the tire change was done in an airworthy fashion.Clearly the mechanic has an ethical obligation is to point out the dent in the wing to the owner and advise the owner that he does not consider the aircraft safe to fly with that dent. However, the mechanic is completely out of line if he refuses to sign the 43.9 logbook entry for the tire change or otherwise attempts to coerce the owner into not flying the aircraft. It's the owner's decision whether or not the aircraft is safe to fly, not the mechanic's.Under the regulations, the mechanic is responsible for doing the maintenance as directed by the owner, and doing it in an airworthy fashion. The owner is responsible for the airworthiness of the aircraft and determining whether or not it is safe to fly. Assuming the aircraft is not being used commercially, the only exception occurs once a year when the aircraft undergoes its annual inspection ... then and only then is the mechanic tasked with determining if the aircraft is airworthy.If the mechanic in the previous scenario were absolutely determined to ground your aircraft, there is only one legitimate way for him to do it: Call the FSDO and persuade an FAA inspector to come inspect the aircraft and hang a condition notice on it. FAA inspectors do have the authority to ground an aircraft, but mechanics do not have that power.

A Happy Ending

Returning to where we started, I'm pleased to report that our Cessna 340 owner's tale had a happy ending. Encouraged by me and several other IAs, and armed with newfound knowledge of the regs, the owner appealed to Galvin's general manager of maintenance:

"I went in today to talk to the GM of the maintenance business. He walked out on the shop floor, talked to the mechanics, and figured out what had happened."He then apologized profusely to me. He explained that a new supervisor, coupled with him being on vacation, had screwed things up. The swing shift had gotten out of control on my airplane and racked up the hours."He talked to his main maintenance supervisor and had him do a back estimate of what the troubleshooting and the two squawks that they fixed without my authorization involved. The 60 labor hours were adjusted down to 15, and the GM told me that since I did not authorize the work I did not need to pay for the 15 hours. I told him that if he thought 15 hours was a fair estimate for work that corrected my pressurization leaks, then I would have accepted that in the first place and that I would pay."Also on the issue of log books, he said immediately that this work was maintenance according to 43.9 and therefore the shop had no legal basis for holding the plane back. He said that his shift supervisor should have walked down the hall to get answers to this. More apologies."We came out in a fine place, but it didn't need to be this hard. With a little help from my friends and the FARs, we ended up with a good result."

I'm impressed with the Galvin GM's willingness to admit that his folks made mistakes, and his efforts to make things right. That is always the true test of any enterprise. Galvin has long been known as a first-class operation.I'm also pleased that some folks at Galvin received a much-needed refresher course in the regulations and owner/mechanic responsibilities. I suspect Galvin's future maintenance customers will be the beneficiaries of this owner's perseverance.See you next month.

Want to read more from Mike Busch? Check out the rest of his Savvy Aviator columns.