How Smart Is Your Cell Phone?

With much talk about modern avionics in recent years, from glass cockpits to ADS-B, one fact remains unchanged: most aircraft have vacuum systems and gyroscopic instruments that sometimes fail. Although,…

With much talk about modern avionics in recent years, from glass cockpits to ADS-B, one fact remains unchanged: most aircraft have vacuum systems and gyroscopic instruments that sometimes fail. Although, there are pilots flying today’s skies that have never seen a gyroscopic instrument or have had to execute an NDB approach—with such instruments covered—there are many aircraft currently trolling the clouds relying on “old school” gyros.

Sadly, pilots are still perishing when these archaic instruments (or the systems that power them) fail. Recently, a Bonanza pilot and two passengers met an untimely end when a vacuum pump (being operated eleven years beyond its service life limit) failed. While newer aircraft have the luxury of fancy glass—typically accompanied by one or more backups—much of the general aviation fleet still relies on suction and spinning gyros. The question remains, why do many pilots continue to fly without redundancy, especially considering the power that most of us carry everywhere we go?

My Phone Can Do What?

I’m referring to the handy smartphone. You probably know that it has more processing speed and memory than the computers that took us to the moon. But, did you know that most smartphones have a suite of sensors that are fundamentally equivalent to modern avionics systems ordinarily serving as components of glass cockpits? Some examples of onboard sensors include accelerometers, gyroscopic sensors, magnetometers, and barometers. These can provide the detection of attitude, gravity, linear acceleration, and heading. Also, GPS and cellular signals are used for position and speed information.

In short, the typical smartphone has capabilities that go beyond phone calls. New glass standalone instruments have recently been introduced, such as the Garmin G5 and Dynon D10 that essentially have the same innards found in a cellphone. While these new instruments are “relatively” cheap—starting at $2000—you can harness some of the power of the smartphone in a pinch. Let’s take a look at some examples with a note of caution. This is not a comprehensive review, simply my observations of a variety of products. Nor do all applications tested work with both iOS and Android platforms.

Aviation Apps

While there are many different smartphones and a range of applications for each, we’ll focus on the iPhone Model 8 and associated apps flight tested under visual flight rules. Currently, no app can be used as a legal backup for several reasons. First, no app allows you to pull out a phone after an instrument or system failure and have it be calibrated for safe flight. Having the app set up and suitably secured/ oriented in the cockpit is required before it’s needed.

The only way to validate if an application has the essential utility is to do some testing that must include finding a location to mount the phone in a low vibration area, and secure position within the field of view.

Some Capabilities

My evaluation included several apps, though technically only three of those tested claim to be standby instruments. The first was iBFD, which has a glass-cockpit-like display. This app must be calibrated precisely and placed in a location and position within the cockpit so the attitude matches that of the aircraft. Simply, the application has no way of being “zeroed” when flying in level flight. This makes the real utility of this option questionable. Its display of attitude was extremely sensitive and jerky, so it doesn’t react like a flight instrument—even glass.

The vertical speed, airspeed, and altitude features seemed accurate, although the “airspeed” provided was actually groundspeed. However, the heading feature was good enough to use in lieu of a sloshing compass, if needed. Overall, this application has limited use as a backup attitude indicator, but could provide critical data in case of other system failures; such as a frozen static port or a failed directional gyro.

The next app tested was ShcumApp, which can display a conventional attitude indicator or a glass-like display. This app can be “zeroed” regardless of initial phone orientation, so it can be synced to straight-and-level. Once calibrated, the display was consistently accurate, though, like iBFD, somewhat sensitive—moving instantly with slight changes—especially in turbulence. It could function as a reasonable backup. It also has the advantage of digitally displaying degrees of roll and pitch. It does lack other data such as heading, speed, and altitude.

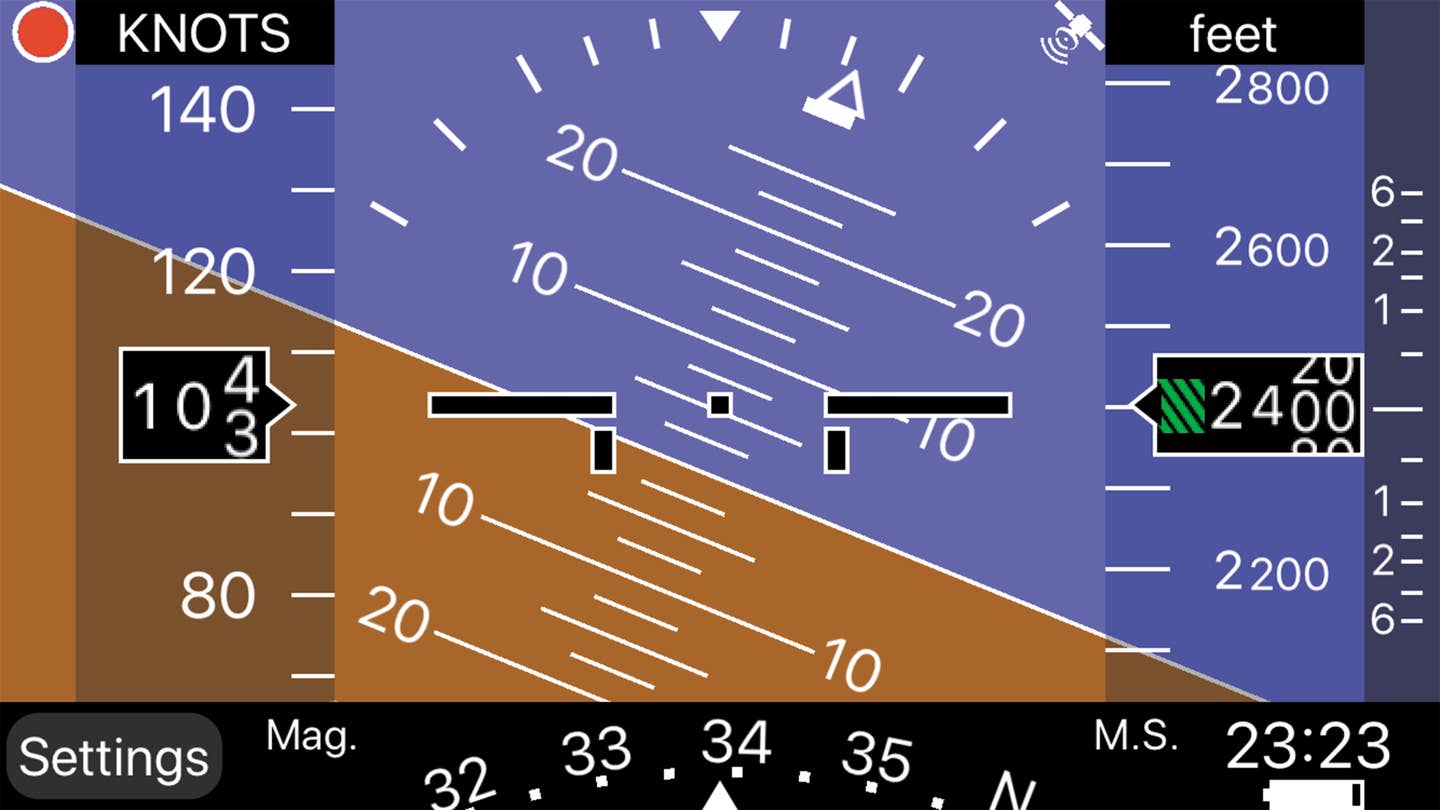

The most capable application as a realistic stand-in for an attitude indicator is Horizon. It provides a display that looks like a high-end gyroscopic AI. It can be calibrated in any position, and it provides flexibility for cockpit phone installation. The best part about this app is that it has a dampening feature, which makes the movements smoother and less prone to vibration. The pitch and bank action of this application are much like a real gyro. Additionally, the digital pitch and bank angles are provided. Just like ShcumApp, there are no heading, altitude, vertical speed, or airspeed indications.

There are many navigation and flight planning apps available and often accessed through subscriptions. Some of these offerings have “pseudo-instruments” that are reasonably accurate. Garmin Pilot has an array of possible backup instruments available that include airspeed (groundspeed), altitude, heading (track), and vertical speed. While not perfect, this suite of instruments could save your life if things get bad in the cockpit.

A wide range of sensor apps can display raw data, which can be used during flight. One example is Sensor Kinetics that provides acceleration, gyroscopic data, a magnetic sensor, gravity and a basic attitude indicator. While this data is not usable to maintain precise flight, it can be used as a reference to aid in dissecting flight conditions. This app also offers flight recorder-like output, which can be helpful for flight instruction as well as historical flight monitoring data such as vibration, G-loads, and more.

Not all applications are worthy or even safe for use. One application tested, AOA Flight Assistant, means well, but doesn’t deliver. This software aims to provide pilots with guidance on angle-of-attack. The initial setup of the app takes extensive tweaking to ensure that the referenced angle-of-attack is accurate, including inputs for angle-of-incidence and initial airplane attitude, though it also provides an option to calibrate the system according to the position of your phone in the cockpit. During in-flight testing the outputs provided were essentially useless because of the lag of the display behind the actual aircraft attitude and its propensity to be affected by turbulence and vibration. Perhaps with more engineering, this might eventually provide useful data. Pilots should carefully evaluate any app they intend to use before needing it. Such evaluation should take place in the specific aircraft in which it may be used—including the proper mounting of the phone.

Summary

Evident from the rapid improvements in smartphone technologies, are many tasks these devices do for pilots that were previously only possible in our dreams. In aviation, we continually need to keep abreast of potential resources that can make flights easier and safer—especially if something goes astray with the aircraft. However, use care not to adopt something just because it’s available—evaluate your options and don’t introduce something that, in the end, makes life more complicated or distracts from the essential tasks at hand. Technology often provides a double-edged sword, too much—or used in the wrong circumstances— can have an adverse effect. But when used properly, and at the right time, it can be indispensable. Consider apps available for your smartphone and give a few a try.

David Ison, a former B737 and L1011 airline pilot with over 6100 hours, is currently a professor in the Graduate School at Northcentral University.

This article originally appeared in the April 2019 issue of IFR Refresher magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to IFR Refresher!