One summer, while flying over the largest wilderness in the lower 48 states, I heard a radio call: “Mayday, Mayday, Mayday. White Cessna… [broken and inaudible transmission].” I heard just enough to understand something bad was happening, but not where. I repeatedly tried to hail the aircraft to get them to repeat their location, to no avail. My attempts, however, did pique the curiosity of other aircraft on the backcountry frequency, all of which were south of my position. None of them had heard the call. I deduced the distressed aircraft must have come from somewhere north of my position, so I turned to head upriver where the most likely airstrips were and tuned to 121.5 MHz to listen for an ELT.

I was flying a U.S. Forest Service mission at the time, so during my turn, they contacted me on the dispatch frequency to ask if I had an emergency. The USFS flight following operation was monitoring 122.9 MHz and had heard my call, but not the original Mayday. After I confirmed that I was okay and relayed what I knew, the USFS Central Idaho Dispatch called the county sheriff to report the event.

Coordination

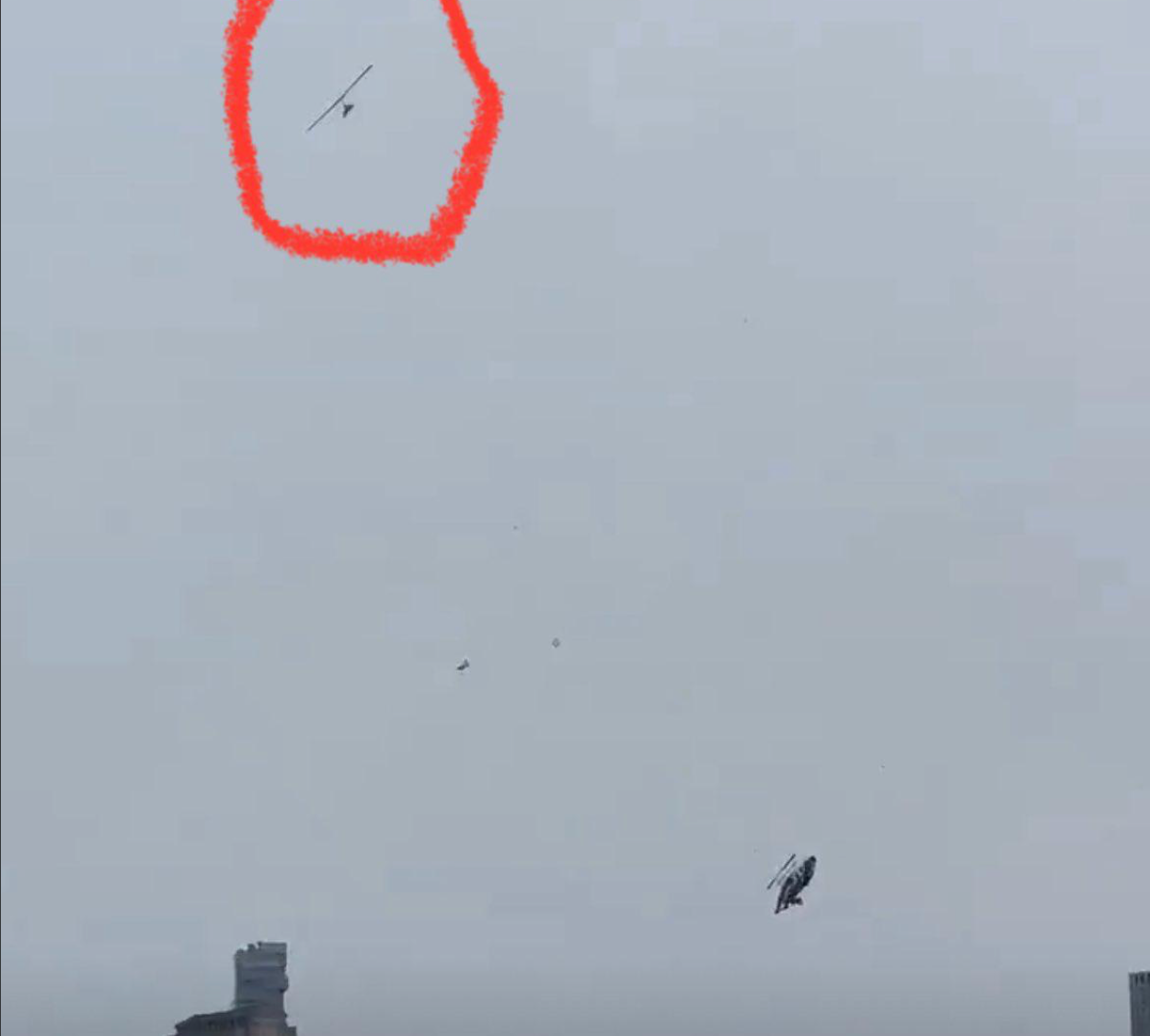

Unknown to me, at about the same time I reported the Mayday call, a pilot on the ground at the Flying B. Ranch in the Frank Church River of No Return Wilderness had seen an aircraft depart, struggle to climb over the adjacent Bernard airstrip, then subsequently turn up a ravine that rose faster than an airplane can climb. The crash and subsequent fire were reported to the county sheriff via satellite phone by the witness. Based on the combined information, and knowing they were the closest resource, the USFS sent a “Helitack” helicopter-borne firefighting team and medical helicopters toward the accident site.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Air Force Rescue Coordination Center (AFRCC) based at Florida’s Tyndall Air Force Base picked up an activated ELT signal and corresponding position. Per protocol, they contacted the Idaho Division of Aeronautics, who by this time was already on the phone with the county sheriff. Within a few minutes, all three distress signals—the Mayday call, the satellite phone call and the ELT—had worked through the system to a central point of contact. A well-coordinated picture of what had happened was emerging.

Those in charge of rendering rescue and first response, and all of the agencies, were following the National Incident Management System, a comprehensive, national approach to incident management applicable at all jurisdictional levels and across functional disciplines. The closest assets—USFS helicopters fighting nearby fires—were self-dispatched to the scene with the knowledge they were looking for an airplane crash and fire in a canyon above the Bernard Airstrip. They were fed what was known about the circumstances of the crash, including information from the eyewitness and the ELT’s coordinates. When the Helitack team arrived on scene, they could see the two reported occupants had survived and escaped the smoldering aircraft. They were lucky to find a suitable landing spot near the crash site and began firefighting, initiating rescue and relaying critical information back to both the sheriff and the Idaho Division of Aeronautics.

Redundancy

“The ELT was registered, so we had an N-number and a contact number for the aircraft,” said Jim Hinen, search and rescue coordinator for the Idaho Division of Aeronautics, the lead agency for responding to downed aircraft in the state. “It was a difficult phone call, not knowing who I was talking to on the other end. It turned out to be the wife of the pilot. I explained that the reason for the call was we had an activated ELT.

“Fortunately, while still on the phone explaining the situation to the pilot’s wife, word arrived from the USFS helicopter crews that the two people on board the aircraft had survived and rescue efforts were underway. It was good to already have good news.”

This accident response was a textbook example: communications went extremely well and rescuers were both exceptionally equipped and exceptionally close. Resources from the nearby Helitack base were swiftly on the scene, and two medical evac helicopters were staged on a runway a mile from the crash site once the severity of the injuries became clear.

Why did the response go so well when the crash was in such a remote area with no cellphone service? The answer is redundancy. The airplane’s ELT activated, so AFRCC received data from its signal. The Mayday call was overheard and relayed to an agency with nearby rotary wing firefighting resources, including Helitack and MedEvac assets. The crash was witnessed by a pilot who accurately recognized what had happened and who happened to have a satellite phone.

Not So Seamless

The crash was gruesome; both occupants received full-body second- and third-degree burns, there was a smoldering aircraft to deal with at the height of fire season, and victims and rescuers alike were attacked by swarms of stinging insects. Despite it all, rescue operations were extremely quick and the outcome was as good as it could have been.

Rescue operations aren’t always so seamless. Earlier in the summer, there was another crash on a backcountry strip. It was witnessed, there was a positive 406 ELT transmission and a SPOT PLB messenger was used to request rescue for a pilot with severe facial injuries, multiple leg fractures and a severely lacerated wrist. On the plus side, immediate medical attention by the two well-equipped pilots on the ground perhaps saved the victim’s life. They had excellent first aid equipment, including gauze impregnated with blood-clotting agents.

The rescue, however, was impeded by human error and weather. Somewhere in the process of communicating the location of the accident, the latitude and longitude were transcribed incorrectly. Latitude and longitude can be written down as degrees, minutes and seconds, or as degrees and decimal increments, or in some combination. As a result, the rescue helicopter wasted time searching for the crash site approximately 12 miles from the actual one. When the rescue finally did arrive, fuel was too low to make a direct flight to a major city without a fuel stop and the weather, which was marginal, closed in. By the time rescue was accomplished, the route to the hospital was in IMC, requiring an aircraft change. The victim survived, but the rescue took five hours…longer than it perhaps needed to be, but still fairly swift. Despite the modern assets usually deployed, search and rescue (SAR) of downed aircraft in remote locations often (and typically) takes more than 24 hours.

Hinen described two other more recent accidents that triggered the search-and-rescue (SAR) rescue system differently. In one case, a pilot was involved in an accident in which the ELT was not activated. Fortunately, the pilot was equipped with a 406 MHz personal locator beacon (PLB). When activated, a PLB triggers the COSPAS/SARSAT system, a worldwide system operated by international participants. Since PLBs are not specifically aviation-related, AFRCC contacts the appropriate local SAR lead agency based on the lat/long location and respective individual agreements with the states. In most states— though not all—the lead agency for responding to PLB activation is a county sheriff. Once an accident is determined to be aviation-related, however, the appropriate state agency responsible for aviation accidents takes ownership.

The second case Hinen mentioned involved an unregistered ELT activation. These are problematic because with no registration, there is no N-number, aircraft description or contact information to work with. It was nearly dark when the AFRCC contacted the Idaho State Division of Aeronautics, too late to dispatch SAR aircraft either owned by the state or operated by the Civil Air Patrol, so the nearest county sheriff was contacted. He immediately recognized the location as a private airstrip. The airstrip owner was contacted, who confirmed a hard landing had triggered the ELT, which he reset. Case closed—no harm, no foul—but an unregistered ELT makes for more guesswork. If it had been an actual crash, SAR assets likely would not have been deployed until first light the following day.

Leveraging Communications

Register your ELT. It makes a big difference. Even when it is not required, as with 406 ELTs, just do it. When you register, you have an opportunity to provide additional information, including alternate emergency contacts and other notes like special needs that might aid SAR teams. Every bit of information can jump the rescue efforts further ahead. “When an ELT is registered, we immediately know the identification of the aircraft involved, and the name and contact information for the registrant,” said Hinen.

Don’t count on a sudden stop involving aircraft damage to always activate an ELT. Sometimes the antenna is sheared off or destroyed by a post-crash fire. And sometimes an upside-down aircraft will prevent the signal from reaching out. When you know you are going to crash, all pilots should attempt to maintain positive control of the aircraft all the way through the accident sequence.

But if you know the outcome is going to be bad, why wait for the crash to trigger your ELT when you might be able to activate it from the cockpit? Setting off the ELT manually gets the ball rolling before the mayhem. When I fly new aircraft, I look for an ELT activation switch. I also brief my passengers on its location because the front-seat occupants are more likely to have head injuries.

Inform someone about your departure and expected return. In the first incident I described, the pilot had told his wife that he was departing and provided her with an expected time when he would be back home. Had none of the other systems been triggered, his wife still would have been able to alert authorities and provide the departure airport and time of last contact. Such information is gold to SAR. None of us wants to be in a crash or at the root of a distress call. If, or when, the time comes, understanding what you have triggered may help you make better preparations and smarter choices that hopefully will significantly quicken your rescue.

Distress Signal Processing

When your ELT goes off, the U.S. Air Force Rescue Coordination Center (AFRCC) receives its signal via the satellite-based COSPAS/SARSAT network. The AFRCC operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week from Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida.

The AFRCC is the United States’ inland search-and-rescue coordinator, the single agency responsible for coordinating on-land federal SAR activities in the 48 contiguous states, Mexico and Canada. It is directly tied to the FAA’s alerting system, the U.S. Mission Control Center and to the organizations that conduct or assist in SAR efforts throughout North America.

When a distress call is received, AFRCC first tries to verify that it’s legitimate. In an ELT activation, they will try to contact the registrant. Then they choose the rescue forces needed based on availability and capability of forces, geographic location, terrain, weather conditions and the urgency of the situation. Priority is given to local jurisdictions including any state agencies, local or civil SAR resources. Individual states may operate differently. The AFRCC can also coordinate with Civil Air Patrol, U.S. Coast Guard or other Department of Defense assets.

Not All 406 ELTs Are Created Equal

In 2009, the SARSAT system stopped monitoring 121.5 MHz ELT signals, which are notoriously difficult to locate. While a 406 MHz ELT provides much more precise location information, non-GPS versions still only get SAR folks within two to five miles of a location. In rough terrain with tree-covered canopy, that’s a much larger area to search than it may seem. Meanwhile, a 406 MHz ELT or PLB signal incorporating GPS can provide location accuracy to a few tens of meters. There are two basic ways to ensure GPS data is available in your 406 MHz ELT’s signal: Wire the ELT to your aircraft’s installed GPS navigator or buy an ELT with a GPS sensor built into it. This will improve accuracy. Incorporating GPS can provide location accuracy to a few tens of meters.

ELT False Alarms

Ninety percent of the ELT activations received by SAR resources are false alarms. That’s a lot of robocall-type annoyances for them to patiently sort through while still remaining alert for the 10 percent that are real. Incorrect ELT testing is a major culprit. 406 MHz ELT devices should NOT be tested the same as 121.5 MHz-only devices (by turning them on in the first five minutes after hour.) Instead, any live test of a 406 MHz ELT must be coordinated through the AFRCC (1-800-851-3051). Some ELTs feature elaborate self-testing without the need to transmit. Consult your ELT manufacturer’s documentation for recommended testing procedures.

Who Pays?

If you are injured in a crash, you will probably feel grateful when your rescuers descend from a helicopter, transfer you to a waiting MedEvac chopper, and transport you to a major trauma center in a Pilatus or King Air. Search and rescue is one of those public services we sometime take for granted, but the $2000-plus/hour operating cost per aircraft is not paid in gratitude.

So who pays? It depends largely on the jurisdiction you crashed in and how many resources were required to extricate you from harm’s way.

Many SAR first responders are local volunteers. There is a good chance the person who hiked in from a trailhead to your accident site is unpaid. If the Civil Air Patrol is dispatched to look for a downed aircraft, the cost is covered by the USAF. County rescue personnel are often already on the county payroll, but some counties seek reimbursement. When private air support and professional medical crews are required, the costs can quickly mount and you may get a bill.

One way to hedge against the potential cost of rescue is to purchase SAR insurance. Many PLBs like SPOT and InReach offer various levels of coverage for rescue insurance costs. You can also get policies from the aviation businesses that serve your local or regional community. And your aircraft insurance may include SAR benefits. In many states, you can either purchase a card like Colorado’s SAR card, or you can purchase a hunting or fishing license, which often help fund state and local SAR budgets, and entitles the possessor to rescue coverage (even if you weren’t hunting or fishing). Each state varies. Some provide subsidized services and others allow local jurisdictions to recover costs.

This article originally appeared in the December 2018 issue of Aviation Safety magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to Aviation Safety!