Accident Probe: Ready To Burst

Some mentor, long ago, explained aviation weather to me: “There are two kinds of weather you never want to fly in no matter the aircraft,” he said. “Icing and thunderstorms.”…

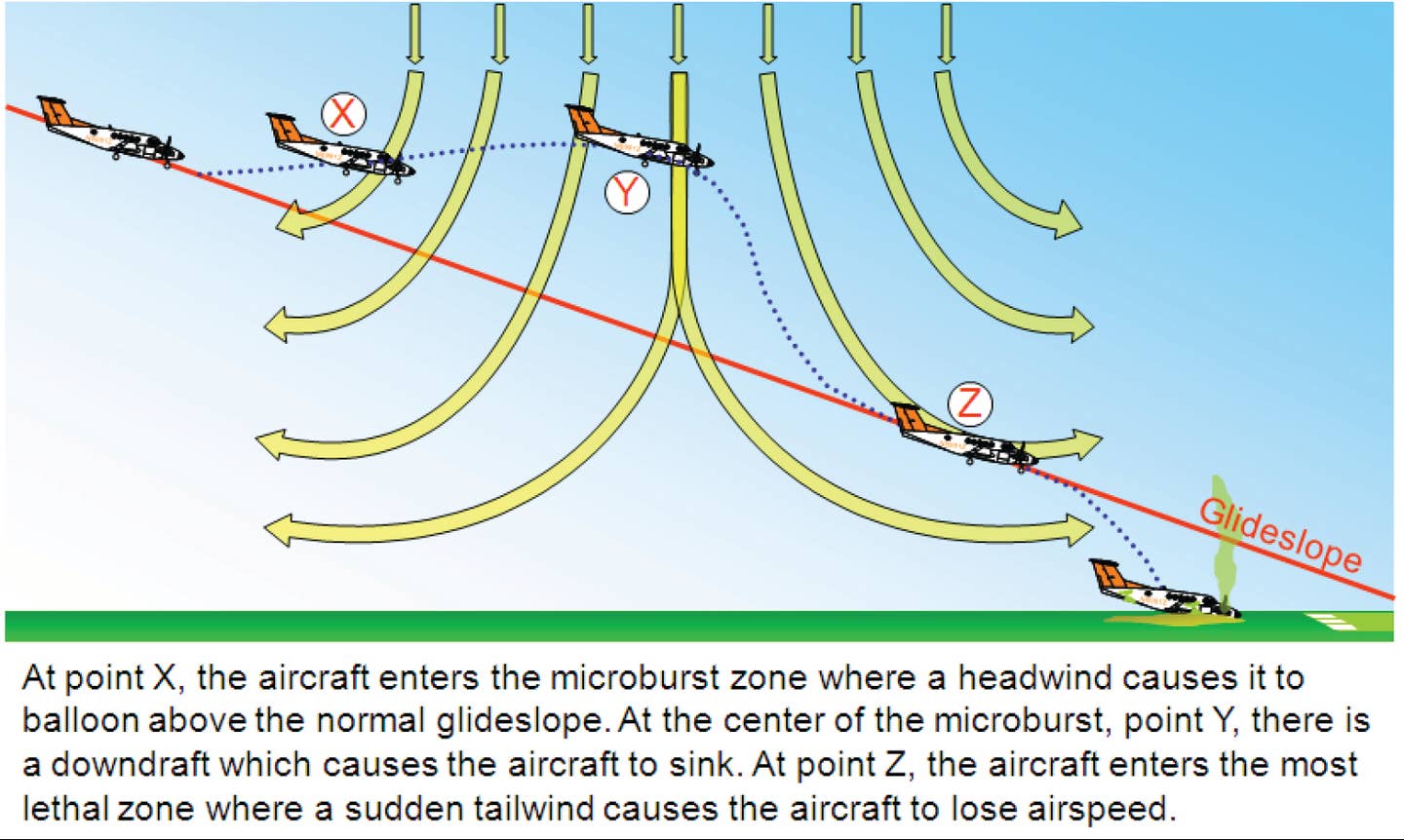

The FAA advisory

circular “Aviation

Weather,” (AC 00-

6B), issued in August

2016, advises that

“Downbursts create

many hazards for

aviation and often

cause damaging wind

at the surface.” The

graphic above is from that AC.

Some mentor, long ago, explained aviation weather to me: “There are two kinds of weather you never want to fly in no matter the aircraft,” he said. “Icing and thunderstorms.” He wasn’t wrong. But until we gain some experience, sometimes it’s hard to tell when we’ve gotten too close to either weather situation. Put another way, it’s hard to know where the line is until we cross it.

For example, it’s easy to say we should stay 20 miles from a mature thunderstorm, but it’s harder to determine what “mature” means. And it means different things in different areas of the U.S. and around the world. Make no mistake: Flying into any thunderstorm is a bad idea. But it’s also common to skirt the edges of one while remaining in visual conditions.

Keep in mind that something “mature” on the march across Kansas or Oklahoma in July isn’t the same as the air-mass storms populating Florida on the same day, for example. It’s hard to make one-size-fits-all pronouncements about thunderstorms and how close you can get as long as you stay in visual conditions, but it’s not so hard to recommend that flying close to or under pretty much any thunderstorm while landing or taking off is a bad idea.

Takeoffs and landings don’t mix well with thunderstorms for two basic reasons. First is that the wind velocity often associated with thunderstorms can easily exceed the typical personal airplane’s airspeed when landing or taking off. Second, we’re close to the ground, sometimes very close, so there’s much less margin for error. And fat, wide margins for error are better than thin ones. Here’s an example of cutting things too close.

History

On May 5, 2017, about 1922 Eastern time, a Cirrus SR22 impacted terrain during a go-around at the Clearwater (Fla.) Airpark (CLW). The 44-year-old male instrument-rated private pilot was fatally injured and the airplane sustained substantial damage. Visual conditions prevailed at the airport at the time of the accident.

The flight departed Mullins, South Carolina, about 1620, and received VFR flight following services from the Jacksonville ARTCC and then Tampa Approach. As the accident pilot approached CLW, he communicated with another pilot and followed him to the runway. As the other pilot landed, he encountered increasingly strong and gusty winds, requiring full aileron deflection to maintain control. He radioed the accident pilot, telling him the wind was “snotty” at the approach end of the runway and to be careful. The other pilot then taxied to parking and did not see the accident airplane approach to land. He was not aware it had crashed until he heard sirens.

Investigation

The airplane came to rest inverted just east of the runway. There was no post-impact fire, and the Cirrus Airframe Parachute System (CAPS) was not deployed. Flight control cable continuity was established from all major flight control surfaces to the cockpit area. The flap actuator indicated the flaps were fully extended; the pitch trim system was found near its neutral position. All three propeller blades were bent aft and exhibited polishing at the tips. No mechanical deficiencies were observed with the engine or airframe that would have precluded normal operation at the time of impact.

An airport employee observed the accident airplane on final approach. He said it was very windy and gusty, and rainstorms were approaching the airport. The airplane disappeared from his view and he then heard the airplane’s engine go to full power. He saw the airplane in a vertical climb before it rolled left onto its back and descended out of view.

Automated weather at CLW shortly before and after the accident included winds from 280 degrees, ranging from 10 knots with gusts to 19 knots before the accident and 14 knots with gusts to 23 knots afterward. Visibility was 10 miles and scattered clouds at 3200 feet AGL were moving through the area, underneath a broken ceiling at 4500 feet and an overcast at 6000 feet.

Analysis of weather radar data for the location and time of the accident showed the airplane was in either very light or light precipitation. There were no lightning strikes around the airport at the accident time. An AIRMET Tango issued at 1645 for moderate turbulence below 12,000 feet was valid at the time. Gusts of up to 30 knots were in the local forecast, but there was no record of the pilot receiving a weather briefing for the accident flight, although he did get a briefing earlier in the day for a different flight.

Review of data from the Integrated Terminal Weather System (ITWS) Situation Display serving the area at the time of the accident indicated that a downburst/ microburst/gust front was moving eastward across CLW around the accident time. The ITWS information is not available to controllers in ARTCCs but is available to airports with air traffic control towers. Clearwater Airpark is a non-towered airport.

As of two weeks before the accident flight, the pilot had total flight experience of about 244 hours, of which 23.6 hours were in the accident airplane.

Probable Cause

The NTSB determined the probable cause(s) of this accident to include: “The pilot’s decision to attempt to land while a line of rain showers with microburst activity was crossing the airport, which resulted in a loss of control during a subsequent attempted go-around.” The NTSB added that the airplane “likely entered an uncontrolled descent and impacted the ground before the pilot was able to raise the flaps” to 50 percent, as the airplane’s Pilot’s Operating Handbook requires during a go-around.

It’s possible that the pilot wouldn’t have attempted the landing if he knew there were 30 knots of wind in the forecast, but it’s not likely he didn’t know there was nearby convective activity. After the preceding pilot warned him of the “snotty” winds on final, he had an opportunity to initiate his go-around well before getting too close to the ground. But he didn’t take it.

Instead, the pilot lost control after encountering what appears to have been a microburst. When he added full power to stop the descent and get the airplane climbing again, it’s likely he didn’t anticipate the sudden pitch up, and hadn’t had time to partially retract the flaps. A little more practice in going around, and managing pitch when full power is suddenly applied right above the runway, might have prevented this accident.

In The Danger Zone: Microburst Characteristics

Aircraft Profile: Cirrus Design SR22

OEM Engine: Continental IO-550-N

Empty Weight: 2225 lbs.

Maximum Gross Takeoff Weight: 3400 lbs.

Typical Cruise Speed: 170 KTAS

Standard Fuel Capacity: 92 gal.

Service Ceiling: 17,500 feet

Range: 1049 NM

VS0: 60 KIAS

Jeb Burnside is the editor-in-chief of Aviation Safety magazine. He’s an airline transport pilot who owns a Beechcraft Debonair, plus the expensive half of an Aeronca 7CCM Champ.

This article originally appeared in the May 2020 issue of Aviation Safety magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to Aviation Safety!