Human Factors: A Lethal Game of Chance

Would you like to play a game of Russian Roulette? To make it more interesting, what if we load five of the six chambers. If you think those odds are…

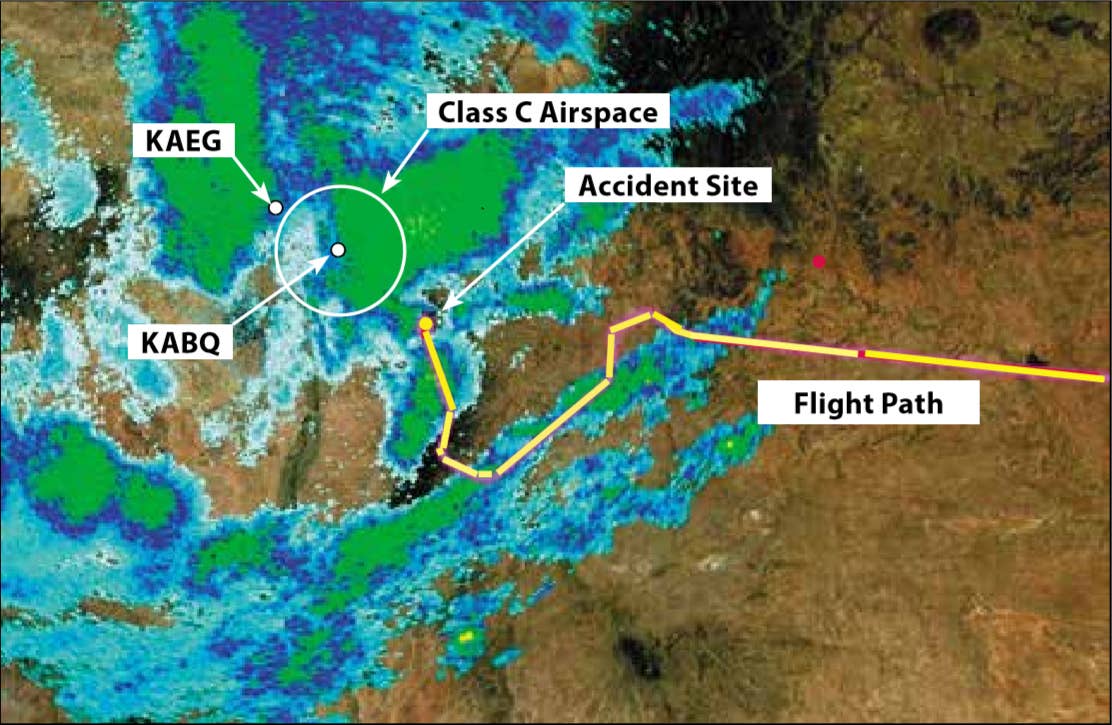

Flight path (yellow line) and key locations are noted amongst the weather.

Would you like to play a game of Russian Roulette? To make it more interesting, what if we load five of the six chambers. If you think those odds are poor, then consider that flying VFR into IMC conditions are about the same.

Too often many general aviation pilots place themselves in IMC situations and then fail when it comes to Aeronautical Decision Making (ADM)? Over the years, the lethality of an IMC accident has had a similar rate as the deadly game above—which consistently hovers around 80-percent.

The overall general aviation accident rate is down. But, as a group, we need to step up our ADM game whenever weather is involved. Here is an example of a straightforward IMC accident with ADM being the root cause.

The Aviator

The 35-year-old pilot held a commercial certificate with single- and multi-engine land ratings, with an instrument rating. He also held a mechanic’s certificate with airplane and powerplant ratings with inspector authorization.

The NTSB reviewed the pilot’s logbooks and determined that during a seven-year period prior to the accident, he had flown 700.1 total hours of which 648.8 were as pilot in command. These hours were further broken down as 498.3 hours in single-engine airplanes; 205.2 hours in multi-engine airplanes; 577.4 hours of cross-country time; 95.6 hours of night flight; 60.5 hours of dual; and 33.3 hours in the make and model accident aircraft, a 1964 Cessna 182G.

Additionally, the NTSB noted the pilot flew 45 hours of actual IMC and 11 instrument approaches during the six months before the accident. One would have to assume he was instrument proficient.

However, investigators questioned if the pilot had a current flight review. They were only able to find evidence for a single such flight being logged during the five-year period preceding the accident—and this entry was over four years old.

Nor did the NTSB note the pilot having added a flight certificate or rating within the two years prior to the accident either of which would have fulfilled the requirement for a recent flight review. This leads us to believe the pilot was flying without a current flight review—raising questions about his judgment and decision-making ability.

Las Vegas Trip

The pilot was the principal in an aviation business located at Kickapoo Downtown Airport (KCWC), in Wichita Falls, Texas. According to a company employee, the pilot, a fellow business partner and the business partner’s wife departed at about 10:00 a.m. local on a November flight to Las Vegas, Nevada—a straight-line distance of over 800 miles.

According to investigators, there was no record of a weather briefing for the flight. But, with today’s internet, it’s not uncommon for a pilot to self-brief, sometimes with sites that don’t record the pilot’s access. However, considering the flight’s distance relative to the pilot’s reported experience, it would have been prudent to go further by speaking to a flight service briefer or getting a formal online briefing. This is especially true since the distance and the time involved would likely have the Cessna crossing areas of IMC and/ or other adverse weather conditions.

Moreover, no flight plan was filed. While not a legal requirement for a VFR flight, it would be wise for ATC to have a record of one’s basic information and intentions for a trip of this length, especially over desolate terrain. At the least, a request for flight following services should have been in order. Having another set of eyes and ears to assist with weather and traffic alerts is an added safety net.

Instead, the aircraft departed on its journey with the transponder set in Mode A, instead of in Mode C, so no altitudes were captured by ATC. The decision to set the transponder to Mode A was likely spurred by the Cessna not having the required pitot static system and transponder-encoder tests in over three years.

At this point, we need to seriously question this pilot’s judgement and his ability to follow basic aviation rules.

The Weather Encounter

A photograph taken by a passenger in flight shows the airplane traversing desolate mountainous terrain in VFR conditions below a cloud deck with weather in the distance. Another photo shows the airplane flying over a solid undercast. It could not be determined where the photos were taken. However, given the time of year, and the temperatures aloft (at the required terrain clearing altitudes) why would a pilot fly an aircraft, not certified for flight in icing conditions, over a solid undercast? Yet another indicator of questionable ADM. This action would become the catalyst that set the accident chain in motion.

As the airplane approached its planned midpoint stop, Double Eagle II airport (KAEG) in Albuquerque, New Mexico—near the Sandia Mountain range—it deviated from its westerly course by first turning southwest, then north. This was likely a reaction to a wide area of IMC weather with light precipitation near the destination. The icing severity and probability charts showed a potential for icing in the area starting at 7500 feet and increasing in severity and probability with altitude.

It was also the first time the pilot contacted any ATC facility during the flight. The pilot called the Double Eagle control tower, when 25 miles to the east, stating he was “descending out of 13,000 feet, trying to get over weather but we couldn’t get high enough to make it work, kind of in between layers.” The pilot requested an ILS approach into the airport, but erroneously reported his distance from KAEG as less than five miles. The pilot was given a frequency and was told to contact Albuquerque Approach for a short range IFR clearance.

When the pilot radioed Albuquerque Approach, he again erred when reporting his position as five miles east of KAEG. This hampered the controller trying to find the aircraft on radar. It took some time for approach to find the Cessna, but with help from Albuquerque Center the aircraft was finally identified. It was in an area with a minimum en route altitude of 11,500 feet and having a more than 60-percent probability of light to moderate ice.

Due to terrain, radio communications with the pilot were poor, so the controller had to relay information through a passing air carrier flight. The information included an altimeter setting. But transmissions received by the controller were worrisome... “pretty hairy… I can see the ground… I’m just trying to maintain visibility right now.”

It’s obvious that stress and possibly hypoxia were taking their toll on the pilot’s decision-making ability and his basic attitude instrument flying skills. It was also the likely cause of the pilot not performing two basic actions—updating the altimeter setting and more importantly turning on the aircraft’s pitot heat. The NTSB noted the failure to set these two items when investigating the wreckage.

It is unknown, but ice was likely also accumulating on the airframe. The remainder of the flight was an erratic flight path indicative of spatial disorientation. There were no survivors after ground impact at an elevation of 7634 feet about 22 miles east of KAEG.

The NTSB determined the following probable cause: “The pilot’s continued visual flight into instrument meteorological conditions, which resulted in spatial disorientation and a loss of control.” The report went on to list additional factors, the first on the list under the heading Personnel Issues was: “Decision-making/judgment - Pilot (Cause).”

ADM And Risk Management

The concepts of aeronautical decision making, and risk management go hand in hand. Unfortunately, they also get brushed aside with the common misconception that both processes are just plain old-fashioned common sense that can be done on the spur of the moment. Nothing can be further from the truth, as both these processes are systematic approaches to making decisions and managing risk. Both require forethought on the part of the pilot-in-command.

The FAA uses some trite mnemonics such as the 3Ps, DECIDE and IMSAFE for these models— that tend to make it easy to dismiss the concepts. But these memory aids are minimalist versions of robust decision making and risk management techniques used by the airlines, the military, and large corporations.

Consider scheduling time with an instructor (or a more experienced IFR aviator) to create a personal minimums worksheet and then run some flight scenarios that require decision making. Do this over some refreshments on a day when you can’t go fly—for pilots, talking aviation is the next best thing to flying.

Doing this on regular basis, especially before any significant trip, can only help. Incorporate this activity into a flying club or aviation organization meeting. No one has all the answers, and group discussions can help.

The idea is to keep ADM and risk management as our most important resource when flying rather than a chore to be considered when convenient. It needs to be spring loaded to help us make good decisions before we aviate—and while we fly.

Article is based on NTSB Number: CEN16FA042

Amand Vilches is a commercial pilot and instructor who lives in Brentwood, TN. He is a past Nashville District FAASTeam Honoree. His extensive background in risk management and insurance allows him to bring a unique perspective to flight instruction.

This article originally appeared in the November 2019 issue of IFR Refresher magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to IFR Refresher!