Keep Up The Good Fight

The clock read a few minutes past noon when I pulled through my control tower’s entry gate. As always on my way into work, I took in the weather conditions,…

The clock read a few minutes past noon when I pulled through my control tower’s entry gate. As always on my way into work, I took in the weather conditions, mentally prepping for the day ahead.

A scattered cloud deck mottled the blue above. What drew my eye most, though, was a pocket of cumulus clouds quickly rising to the west, aspiring to cumulonimbus status. I had a feeling I’d be dealing with the product of that convection shortly—and I wasn’t wrong.

As the afternoon wore on, that little cloud pile would make things complicated. How would ATC and pilots adapt and keep working as the weather continued throwing obstacles in their path?

The Phantom Menace

The pre-duty weather briefing indicated we’d be getting some isolated thunderstorms in the afternoon. At this particular time of year, it was never a question of “if” or “when” the storms would develop. They were like clockwork. The most important question was: Where?

I plugged into a radar scope to relieve a controller who was working final. He told me that, so far, weather hadn’t been a factor. All aircraft were still on normal, expected routing. Departures took off to the east, with easterly winds about eight knots.

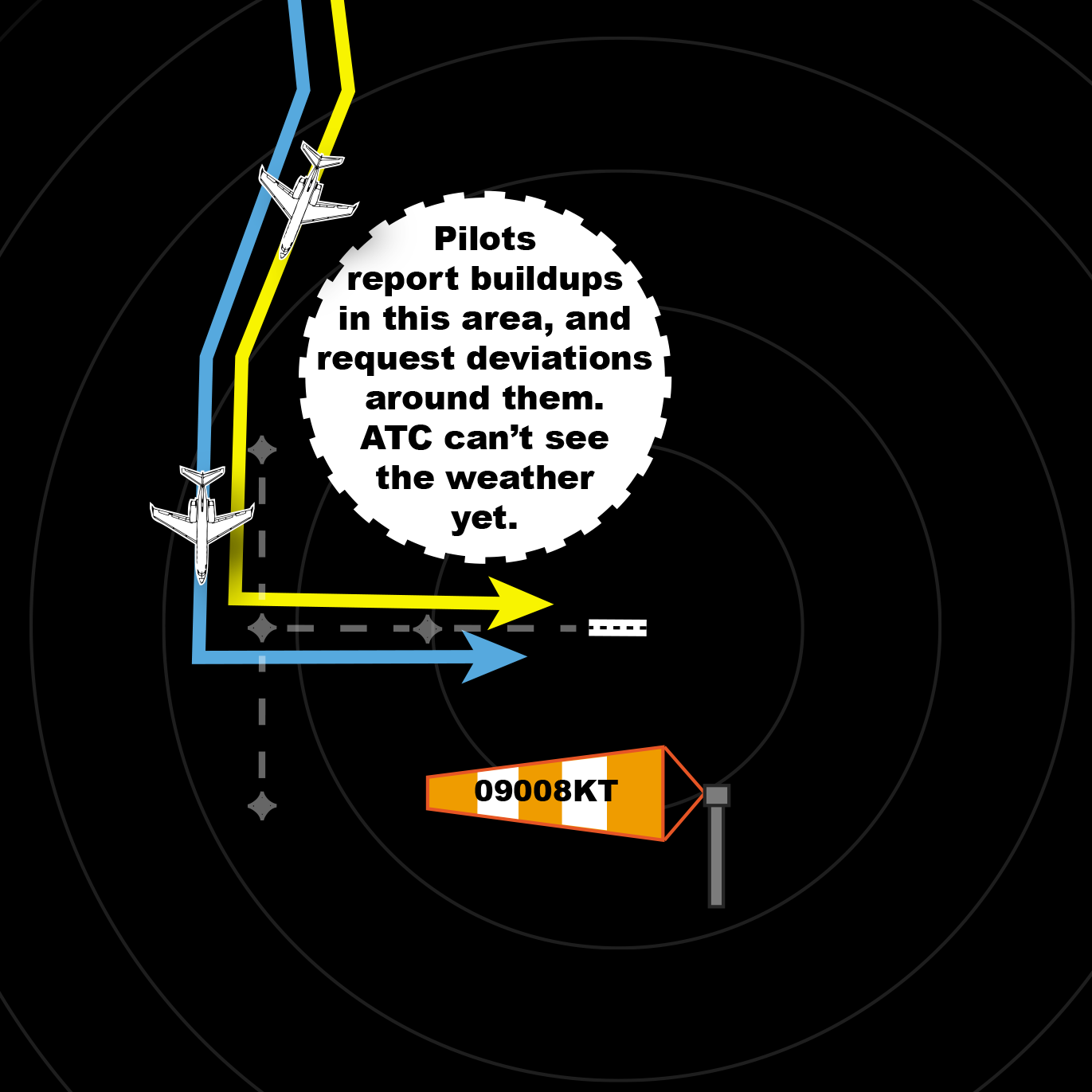

No sooner had I said, “I’ve got it,” when an inbound airliner called. “Approach, I’ve got some buildups ahead. Request right deviation.” It starts. Settling into the still-warm seat, I transmitted, “Deviations right of course approved up to 20 degrees. When able, fly heading 180 and advise.”

Eyeballing his route, it appeared to be the same building clouds I’d seen earlier outside. Our radars can only see precipitation (rain, hail, snow, etc.). At this stage of a storm’s growth—where it’s only cloud formation—we depend wholly on pilot reports to build our mental picture. His request and report gave me crucial information.

I had a few airliners in trail of him descending on the same arrival. I also had other crossing traffic at 6000 and 8000 feet. Knowing it was probable the other airliners would request deviations, I kept the crossing traffic away from them, so there was room to maneuver. Sure enough, the deviation requests came in, and I approved them, same as the first.

My information gathering continued. I watched when each aircraft deviated, noted when they advised their turn to the assigned heading, then observed when they’d be able to turn towards the final. This allowed me to get a general position on the still-invisible-to-me storm, and illustrates why the “…and advise” portion of a deviation instruction is so crucial.

Based on the flight paths, I guessed where the storm might put its foot down: only a few miles north of our final approach course. Oh, this would be fun...

Coming in Hot

Soon, patches of blue formed on my radar. Rain was now falling out of the maturing storm, more or less where I’d expected it: west of the airport, its northern edge about three miles north of final.

It quickly intensified and spread into a mass extending from abeam the final approach fix to out past the initial approach fix—maybe eight miles in diameter. Pockets of green with dense polka dots—extreme precipitation— began to fill it. Not good.

At first, arrivals were able to track final inbound, keeping the storm off their left wing. That didn’t last long. The storm eventually expanded onto the outer reaches of the final. Straight-in approaches were out.

Five miles and inside still looked good for the visual, though. New plan: vector everyone across and south of the final, and hook them in for a tight right dogleg base. I informed each aircraft of what to expect. Normally we aim for no closer than five miles, so we can give everyone a good, stable approach. That wasn’t happening here. I didn’t want any surprises, and hoped everyone was on their A-game (myself included).

I hooked the first arrival in and asked him to say flight conditions, ready to vector him away if things appeared untenable. He reported the airport in sight, and everything looked good. Excellent. I brought in a couple more behind him.

The last one landed just before the storm spread a tentacle south of the final, impinging on that right base. Whenever the next batch of aircraft got there, they weren’t getting in that way. My break showed up just then. As I got up and stretched out my back, I wondered how things would play out.

In Your Face

When I returned, I was sent up to the tower. (We normally cycle through Radar and Tower throughout the day.) As I took the Tower position, that storm still occupied the same terrible spot. Normally, compact storms have some kind of movement. Some flights may need to hold for a bit, but eventually the weather moves on.

Not this thing. It would end up staying in that exact spot for five tedious hours. It never moved, just kept growing and contracting over and over, to the west of us.

My buddy on radar had a couple aircraft in a hold, southwest of the storm, that had been there a while already. I knew eventually they’d have to divert. No one wanted that. What options were available in the meantime?

What about a different runway? Our airport has two. Normally, we would’ve just brought the aircraft in to the north-south runway. Unfortunately, 18/36 was NOTAMed closed for construction. Outside, our mighty little storm screwed up the final for Runway 9.

However, the final for Runway 27 was nothing but beautiful blue skies. Maybe those flights could land on 27, opposite direction to the active?

The big question: what were the winds doing? Headwinds are obviously preferred for landing and takeoff. My displays were indicating six knots, out of the east, nearly a dead tailwind for 27. Depending on aircraft performance and airline company procedures, though, it might not be a deal breaker. We could only present each crew the information and the option; the choice was up to them.

I called down to radar. “Hey, I’ve got no departures off 9 right now. Winds are out of the east at six. If you want to bring these guys in for 27, go for it.” He replied, “You read my mind. Let me see if they can do it.”

I monitored as he laid out the situation. Two were able to take it, so my friend vectored them for Runway 27 and we officially coordinated for opposite direction arrivals. The third couldn’t legally accept it with the winds, so they continued to hold and hope for improvement.

Swinging the Boat Around

As the second arrival turned off of Runway 27, the winds began to shift out of the west. The strengthening storm’s downdrafts were likely now rolling over our airport. The wind socks at both ends of the runway flipped and flopped, but eventually settled out of the west at around nine knots.

At this point, three airliners called ready to taxi. What options did I have for them? They certainly weren’t going to take Runway 9 with the winds 27009KT. Another issue: on Runway 27, normally departures fly straight out before Departure turns them. I wasn’t about to launch these guys into extreme precipitation four miles off the departure end. The obvious solution was a hard turn … if the pilots could take it.

First, I needed to coordinate and advise radar of my plan. I called my radar buddy again. “The winds are steady out of the west now. I’m going to change to Runway 27. Also, I’ve got departures taxiing out now for 27. Can I get automatic releases on fan headings from 180 to 360?” He approved it, granting me authority to launch departures on any heading from due north to due south. He then began vectoring that third, holding airliner, for Runway 27.

As the airliners taxied out to Runway 27, I described the weather and briefed them on the plan: hard turns away from the weather. As the crews digested the information, I considered where I would park them if they decided to hold on the ground. Getting caught without a Plan B is never fun.

Each ultimately decided to go, as long as they were able to line up on the runway and take a look with their onboard radar. I expected nothing less; the call was theirs to make. I cleared the first one for takeoff with a right turn to 360, and added, “Take all the time on the runway you need. Report rolling or other intentions.” He took the runway, paused for thirty seconds, and said, “Rolling.”

Airliners usually fly as smoothly as possible, staying well inside their performance envelope so they don’t upset the customers. However, I’ve worked enough freighter versions of common airliners to know that the actual airframes usually have loads of performance to spare. The box hauler crews turn tighter, stop shorter, and climb as if they’re interviewing for SpaceX.

This first departure barely had the wheels up in the wells before he racked it hard right to 360, staying well away from the storm’s angry edge. I cleared the second one in the same fashion, but with a south turn. “Whoa,” I said, as he banked left, balancing a hundred tons on a wingtip. Those passengers got a heck of a ride, but they got out.

At this point, I held the third departure short for the straggler our radar had just cleared for a visual approach. While I waited, I noted the storm was getting worse, expanding closer. The arrival exited the runway. I issued the departure’s takeoff clearance, and that’s when the Low-Level Wind Shear Advisory System (LLWAS) alarm went off.

Pinned Down

Again, the storm and its downdrafts got the best of us. The LLWAS showed a 20-knot gain on the departure end. I broadcast the LLWAS advisory on all frequencies, and added it to the ATIS. It would be in effect for 20 minutes. At least the departure wasn’t already on the roll when it went off.

Now, I’ve seen aircraft of all shapes and sizes depart with wind shear advisories in effect. My job is to ensure each pilot is aware of them, of the winds, and of any related weather conditions. If the pilot still wants to depart, that’s up to him, and on him. With that in mind, I issued wind shear information to the departure and asked, “Say intentions?”

“We’ll hold,” he said. I sighed with relief. I’ve read too many incident reports to breathe easy when there’s aircraft flying in wind-shear conditions, even if I’ve informed them.

Looking at the big picture though, no one was going anywhere anytime soon. The 20-minute LLWAS window gave the storm enough time to wrap around the departure end. There was no way out. The airliner ended up shutting down at the hold short line and waiting for another hour before the storm receded enough for him to depart.

That afternoon, pilots and controllers alike had exhausted nearly every option: deviations, roundabout vectors, opposite direction landings, holding, a runway change, and hard turns on departure. At last, we’d arrived at the final one: simply stay put. An airplane is never safer than when it’s sitting still on the ground. That choice was just as viable as any other.

That storm might have been a major headache, but it showed how our collective decision-making process can make the best of a troublesome situation.

It's Your Call

Have you ever heard this one? “The pilot in command of an aircraft is directly responsible….” Okay, I hear some of you groaning. Let’s try again. “The pilot in command of an aircraft is directly responsible for, and is the final authority as to, the operation of that aircraft.” That’s 14 CFR §91.3: “Responsibility and authority of pilot in command.”

ATC doesn’t just think about this occasionally. It’s always on our mind. It’s not our life, our safety, our airplane, or our passengers and cargo on the line. It’s yours.

As you read through each situation in this article, please note how many times we controllers defer to the pilots. That regulation doesn’t care whether you’re in an Aeronca or an Airbus, and neither do we; your authority over your flight’s safety is absolute, regardless of what you’re flying.

Whether it’s a nasty little storm, as in this article, or some other complex situation, we’re here to provide enough information and options for you to make a final decision on how to proceed. From there, it’s our job to help you execute that decision to the best of our ability and as safely as possible.

For more great content like this, subscribe to IFR!