Blog: Remembrances Of Triple-Ace Bud Anderson

Bud Anderson shared with me his method of letting down through cloud over the coast of England after a mission during World War II.

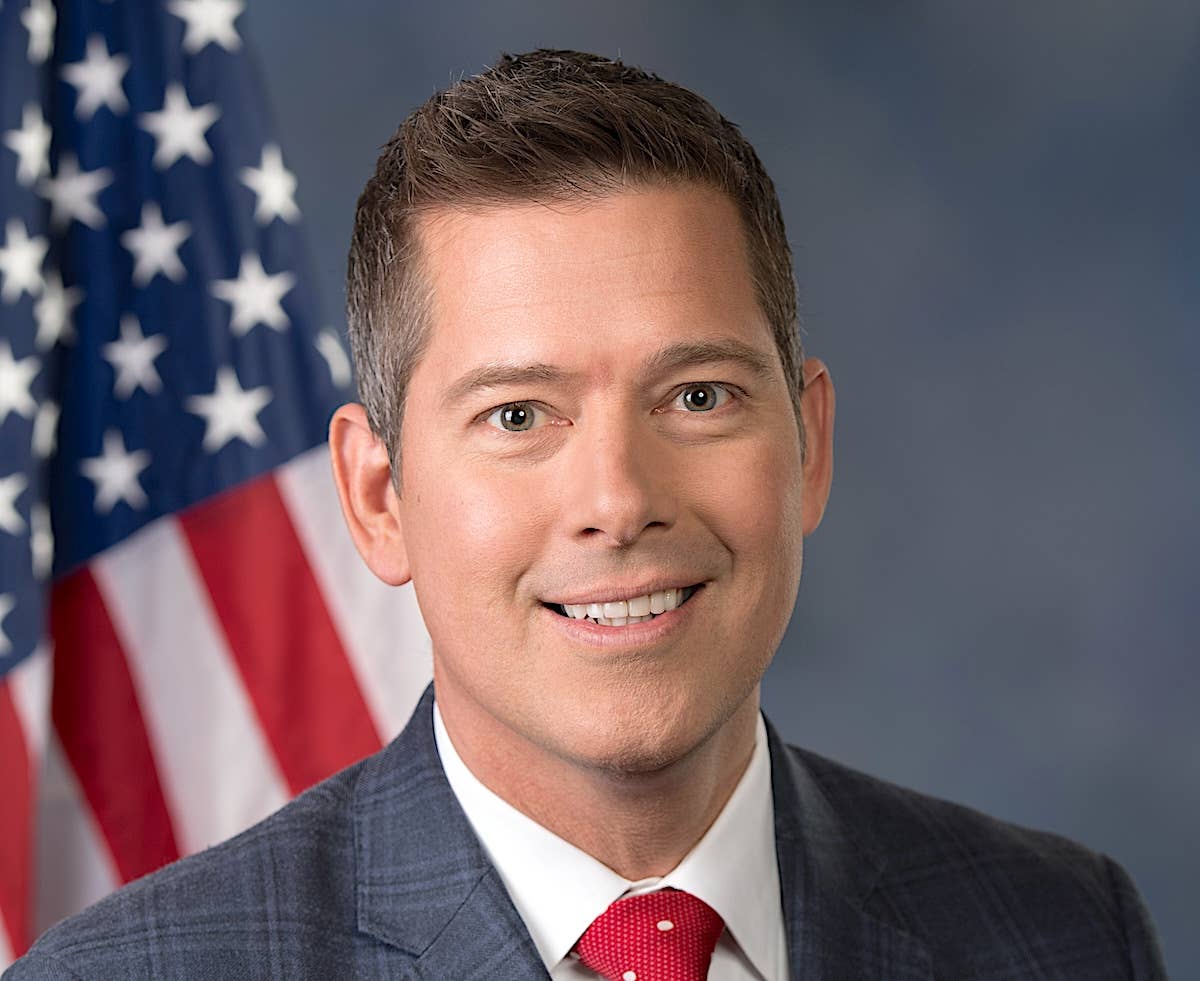

The author with Bud Anderson at AirVenture 2015.

The recent passing of triple-ace Bud Anderson at the well-earned age of 102 stirred up some happy memories along with the inevitable twinge of sadness. I met Bud on several occasions (the accompanying selfie was taken at AirVenture’s Fightertown in the Warbird area), but we seldom had the opportunity for more than a few pleasantries. He was a man in demand.

Each time we met, Bud would always say he remembered me from the last time, but he was so damned polite, so who knew? There was one time, however, when we got to spend some time just chatting about one of the nuances of flying combat in Europe.

I was a regular at the annual trade show sponsored by the National Business Aviation Association (NBAA). On slow days, I’d wander the aisles hoping to happen on something of interest that I could write about.

I can’t place it in time, but it was several years ago, at one of the more modest display booths (you could get lost inside some of the big ones). There sat Bud, surrounded by copies of his memoir “To Fly and Fight.” I wish I could remember the company that brought Bud to the show as their guest, but good on them for honoring a real American hero, even if he looked a bit out of place among all the suits and glitter. I told him I had a well-worn copy of his book at home and he said he’d be happy to autograph it the next time I saw him at Oshkosh. Foot traffic was slow, so I lingered awhile.

I have long studied the Debden-based 4th Fighter Group, a friendly rival of Bud’s 357th, so I asked him for his impression of the ex-RAF Eagle Squadron pilots. He chuckled and said something about how they envied the posh steam-heated barracks the 4th enjoyed at Debden, a permanent RAF base. The 357th pilots slept in coal-fired Nissen huts.

For some reason, a conversation I had with Jim Goodson from a 4th Group reunion came to mind. We were talking about the abysmal English weather, and I asked “Goody” how they’d find their way home after a mission over the continent when the low cloud moved in. He recalled a few well-known strategies for descending while over the English Channel, but ended by saying, “Well, you’re a pilot. I’m sure you have that sort of sixth sense of when you’re flying over your home base down there under the cloud.”

I was thinking, “Uh, no, Jim. I don’t.”

So, as this was on my mind, I asked Bud how they would find the 357th’s “home ‘drome” near Yoxford, England. He started trying to describe the let-down process in words, but quickly grabbed a piece of scrap paper and one of the exhibitor’s handout pens. He drew a rough map of the southeast coast of England, including river mouths and other prominent features. Then he dotted breadcrumbs aligned with the precise heading to Yoxford, as well as the bare minimum safe altitude to clear obstacles and expected flight time to the airport. Of course, he remembered all these as if he had done it last week.

It all made perfect sense, and seemed doable … until I reflected later that evening on the fact that he was leading full squadrons of shot-up Mustangs flown at treetop level by 20-year-olds with less than 500 hours in their logbooks. That’s when it struck me how remarkable these men were, and how matter-of-fact they made it all sound when you asked them about it.

It was shortly after that thought that I also realized I should have asked if I could keep that piece of paper. Damn!