CAP Flies COVID Vaccine: An Inside Look

Because of its cold-chain requirement, COVID-19 vaccine is challenging to transport. Here’s how CAP stepped up.

For more than five days in January of 1925, 20 mushers and 150 sled dogs led a relay across 674 miles of the Iditarod Trail in a desperate race to save the community of Nome, Alaska, whose residents were suffering and dying in a severe diphtheria outbreak. Today, we hear echoes of that legendary Serum Run as Operation Warp Speed delivers COVID-19 vaccine to people around the world. Every day, aircrews and aircraft leverage airports large and small to serve as critical elements of the most complex logistics chain in history to help end the pandemic. The story of that mission made heroes of man and dog for generations.

In early December 2020, the Defense Coordinating Element at Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Region V started coordinating resources to fly COVID-19 vaccine to several Wisconsin and Michigan locations. FEMA made the request on behalf of the Indian Health Service, an agency within the Department of Health and Human Services that provides comprehensive health services for approximately 2.6 million American Indians and Alaska Natives who belong to 574 federally recognized tribes in 37 states.

A Coast Guard crew from Air Station Traverse City flying an MH-60 Jayhawk delivered the prime dose of vaccine in December. Then the Civil Air Patrol was tasked with transporting the booster doses needed to complete the immunizations. This is where I became part of this story.

While most of the COVID-19 vaccines can be shipped by traditional logistics companies like UPS and FedEx, there are some cases where the cold chain's unique distribution and handling requirement require a more flexible approach. One such case is the IHS primary distribution point in Bemidji, Minnesota, which serves clinics spread across the Midwest. IHS needs the vaccine to be delivered within eight hours of it coming out of ultra-cold freezers.

But the drive time to some reservations could be 30 hours. Large cold-shipper containers that can keep the vaccine cold for days wouldn't work for small clinics. They could only accept smaller shipments, making less time available when not using dry ice. To make the mission planning even more complicated, once the vaccine went into the medical-grade coolers, those coolers would have to be reconditioned in freezers if delayed by weather or mechanical problems along the way.

Planners had built in a few days of flexibility for us to account for contingencies like the weather. But once the decision to go was made, no less than two hours before departure, the clock started counting down.

CAP pilots are volunteers. As the holidays rolled in, the call went out to pilots and mission-based staff. Flying is a team sport, and this mission was a prime example of how much work it takes to mesh together multiple agencies and get the job done.

Coordination across CAP, USAF, FEMA, and the IHS was critical. I was selected by the Great Lakes Region command to be on the prime crew with Lt. Col Robert Bowden from the Michigan Wing. We both started our flying careers with CAP as Cadets and regularly fly with CAP as instructor and check pilots. A Gippsland GA8 Airvan based near Indianapolis was assigned to this mission because it would offer more flexibility. The Airvan is a utility aircraft. The cabin was designed around the dimensions of 55-gallon drums for bush plane operations in the Australian outback.

A big sliding door makes loading easy, and the ability for us to remove and reposition seats in the field helped make accommodating bulky coolers easier. The larger cabin made it possible for the health services officers to continuously log the cargo's temperature while we were in the air by checking monitors built into the side of each cooler.

Repositioning to Bemidji on January 4th meant more than seven hours of flying for Robert and me. It also meant crossing a cold front that generated an area of dangerous freezing rain with cloud tops that ended up being far higher than forecast.

The Airvan isn't equipped for flight into known icing conditions. The weather had deteriorated along the route of flight, and a wide area of low IFR near Chicago meant stopping short or turning around wouldn't work. Working with ATC, we took a big dogleg over Iowa and diverted to a different fuel stop to keep us out of the bad stuff. Conditions on the other side of that front were better, and we were relieved to find good VFR weather when stopping at Austin, Minnesota, for gas and our destination of Bemidji. Minnesota lived up to its reputation; it was pretty cold when we set down. Hats off to the CAP unit at Bemidji, who coordinated with the friendly folks at Bemidji Aviation Services to bringing the aircraft into their maintenance hangar overnight to keep it ready to fly. We did appreciate the hospitality.

Once we got the airplane buttoned up at Bemidji, the extended team convened a planning call to review the mission's weather. The news on the weather front was not good. Minnesota was very on-brand for wintertime, and the conditions were forecast to be marginal at best along the first couple of stops the next morning. The decision to call an operational pause for 24 hours turned out to be the right one. The next morning ceilings of 100 feet, with visibility of only 1/2 mile with freezing fog, would have made the planned mission impossible. The forecast for the next day, Wednesday the 4th, was a bit more optimistic. When theorist Gen. Giulio Douhet said, "Flexibility is the key to airpower," he knew what he was talking about.

On delivery day, with wheels up scheduled at 8 a.m., the vaccine arrived ready to be loaded at 7:45 a.m. Launching with the sun low on the horizon, with the weather turning out better than was forecast, we could take advantage of a tailwind to delete a planned fuel stop and instead stretched the first delivery leg to just over four hours. We had coordinated with Minneapolis Center before departure, and they had instructed us to let controllers know we were supporting Operation Warp Speed. They gave us direct routing everywhere we asked to go.

We were greeted every stop by law enforcement escorting teams from the IHS. We filled the tanks and were ready to go by the time all the paperwork in the vaccine handoff procedure was complete. Someone was even nice enough to grab me a sandwich and water, which I wolfed down as I stood by the plane. As a crew, we made sure we continually had someone with eyes on the cargo. We were back in the air quickly. Our goal was always to have the plane ready to go before the pharmacists were.

We dodged some buildups on the way to Traverse City but again landed, unloaded, got gas, and continued on in less than 30 minutes. The final leg to Ann Arbor was just as uneventful. And that leg was the most comfortable, because we finally got to turn the heat on in the cabin. We had been flying with minimal cabin heating all day, doing everything we could to help extend the life of the coolers. Our IHS passengers never complained. They are real pros.

"CAP saved the day," said Daniel Frye, Bemidji Area director for IHS, who helped us load up that morning. "We had a large geographic territory to cover with several stops for delivery, and there was an urgent time sensitivity." This mission was just one of the hundreds across the nation in the fight against COVID. By the time we flew this mission, CAP has logged 36,520 volunteer-days nation-wide while performing a broad spectrum of COVID relief operations since the beginning of the pandemic. In the weeks following FDA approval, CAP has transported more than 7,000 vials of vaccine, many being driven by our ground teams when needed. Ours was the first airlift of this scale by a CAP crew. I'm quite proud of that.

I thought a lot about those brave mushers and their sled dogs on this trip. On-demand light aircraft transport offers public health officials access to more than 5,000 public-use airports. Delivering vaccine closer to where it's needed gives planners more flexibility. I'm honored to be in the fight. The many CAP volunteers like Robert and I look forward to doing more. It's why we put on the uniform. I've lost family to COVID-19; I've had friends hospitalized by it, too. This is important work. This is the fight of our generation.

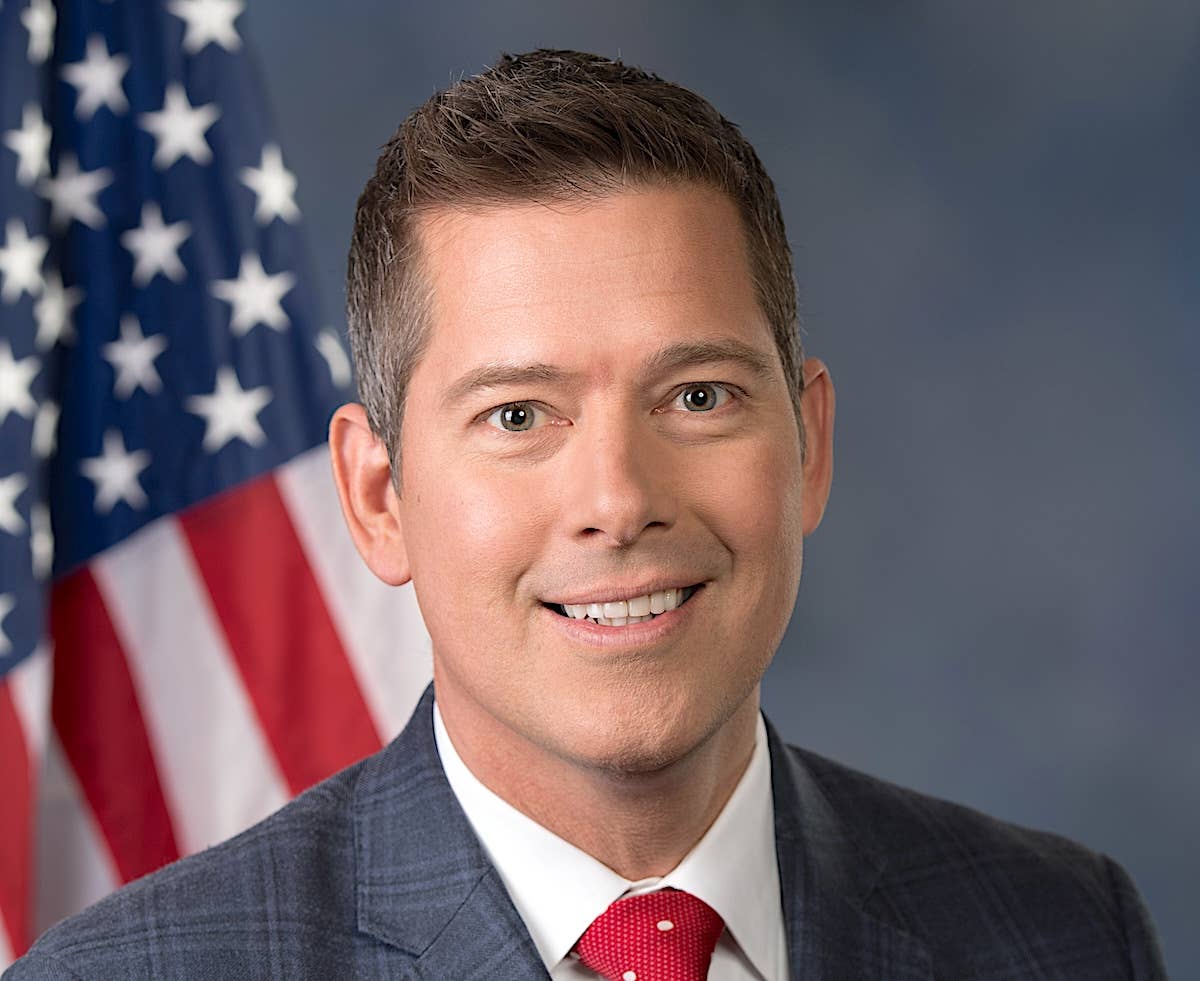

Major Rod Rakic is a long-time member of the Civil Air Patrol.