John Raymond Barcus: A Destiny in Aviation

What’s most remarkable about John Barcus’ life in aviation is that those of his generation didn’t consider their lives remarkable at all.

“I bombed Rome!” the gravelly voice called from a table near the Eagles Club bar. I don’t think my friend, John, appreciated his volume and thought he was whispering to a tablemate. Decades around airplane engines will do that to one’s hearing. A half-beat earlier, I had mentioned that I would be heading to Rome soon. John was merely noting he’d already been there.

“I can’t top that,” I replied and wished I hadn’t accepted this speaking gig at the EAA chapter’s winter party. In my public speaking career, now retired, I’d encountered audience members, powered by Jim Beam, who thought everyone wanted to hear their comments instead of mine. I’ll admit that hecklers’ stories were usually more engaging and certainly more informed. On this evening, though, the voice deserved its say.

John Barcus had, as the cliche goes, forgotten more about aviation than most of us will ever know. My 201 file can’t touch what he accomplished in his lifetime (1921-2006). His aviation resume scrolls like countless others of his generation: flight instructor, FBO owner, airline pilot, airport manager, plus A&P mechanic with Inspection Authorization. I’ve known many younger aviation entrepreneurs with similar credentials, so it’s not a generational slight. Point is, making it in GA is a lifelong commitment that attracts multi-talented personalities, with John being one of the most interesting I’ve known.

Born in Iowa, John Barcus learned to fly in Illinois. At 17, he joined the Army, eventually transferring to the Air Corps (later USAAF) to become a B-24 Liberator pilot. Had he stopped there—war’s over; go home, get a mortgage and new Studebaker—his experience would be far greater than anything I’ve accomplished. Proficiency in warbirds of any kind, in peacetime or war, humbles me no end. John saw combat over Europe with the 8th Air Force, 44th Bomb Group, famously included in the 1943 low-altitude mission over the Ploiesti, Romania, oil fields. Ninth Air Force, 98th and 376th Bomb Groups led in concert with the fledgling 8th Air Force. Casualties were high. According to Air Force historian Dr. Roger Miller, “178 (B-24s) took off on the morning of 1 August … some 88 B-24s, mostly damaged, managed to return to Benghazi. Personnel losses included 310 airmen killed, 108 captured, and 78 interned in Turkey.” Bomb damage results were “less than expected.”

I knew John long afterward when he was instructing in his Cessna 150 or anything available at Osceola (Iowa) Municipal Airport (I75). When not teaching, he’d maintain airplanes to keep us flying and mostly legal. Of small note, he had the neatest penmanship of any instructor or mechanic—like typeset printing. His hearing, though, didn’t improve with time. “What’s the answer to number seven?” he whispered to me in an audio level the entire class overheard during a CFI renewal course final exam. “Question makes no sense!” It didn’t and subsequently was reworded.

John, a founding EAA member, was fun company and often frustrating as old pilots should be, but he rarely talked about combat, until one afternoon while inspecting my Champ, something must’ve reminded him of his final mission as he vaguely waved a torque wrench toward an approaching memory, locking him in place. “I could see it,” he muttered. “Came right at us.” He might have identified the Luftwaffe fighter type, Messerschmitt or Focke-Wulf, but I don’t recall. “Then,” he continued and twitched, “I felt a sting.” Made me twitch just listening.

A sting. The understatement overpowered. Imagine Luftwaffe fighters attacking his four-engine bomber head-on; incoming rounds tearing through the Liberator’s skin and into his, a sensation he recounted over a half-century later as a “sting.” Then, looking past me as though addressing an unseen audience, he said in a voice so distant it nearly vanished, “I cried. Not embarrassed to admit, I cried.” And he returned to torquing re-gapped plugs in my 65-HP engine.

A sting and tears, perhaps not the stuff of Spielberg/Hanks war movies, but instead, a poignant recollection of something infinitely removed from the Midwestern airport where this wounded veteran signed off annual inspections and gave flight reviews.

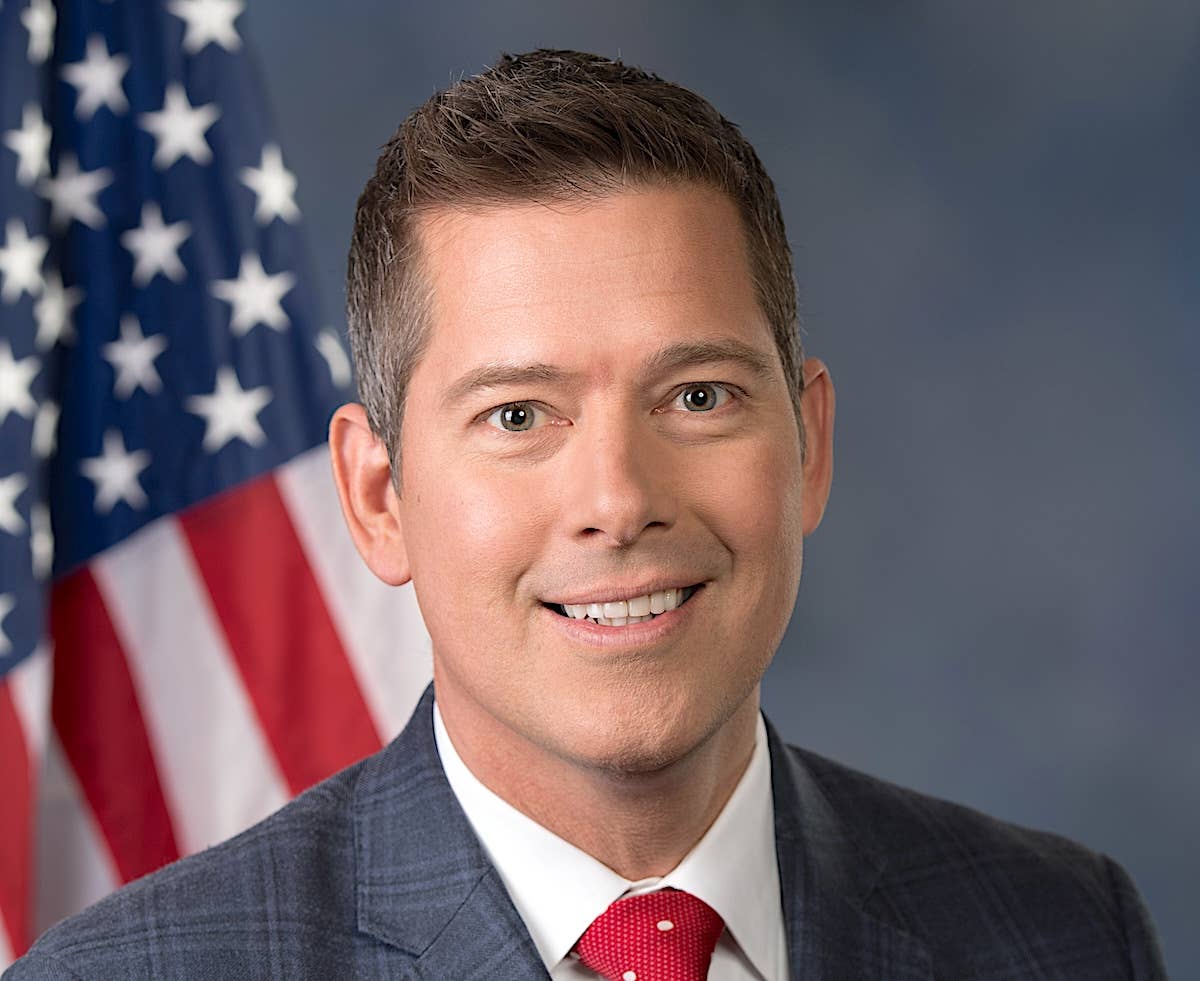

The accompanying photo shows the young John Barcus, bomber pilot. Years ago, John showed me a photo album that included a grainy snapshot of him in a hospital, the diminished survivor of two warbirds screaming head-on with a shared intent to destroy the other, regardless of humans inside or whatever caused them to meet in this converging flash of destiny that would change lives forever.

There’s no moral to this story, no ah-ha revelation from a writer who’s never seen combat. Clio, the Greek Muse of History, won’t allow it. Without comment, she records what she sees but only if she can see it. Countless stories—from all wars—will vanish into the dustbin of fallible human memory if not recorded. I’ve noted a sliver of one here, because the teller can’t. I may have gotten some facts wrong, as my memories of distant conversations also fade. That voice in the Eagles Club who claimed he’d bombed Rome, really had. How, when, and why? I don’t know. He didn’t elaborate, and I didn’t ask, because I was there that night to amuse the crowd with my fluffy ATC tales of localizer approaches gone wild, as they ate stuffed pork chops and peach cobbler.

Airports are repositories of innumerable memories of flights to faraway places on grandiose missions or simply around the pattern on a first solo. Every flight adds to the history of what makes aviation unlike other human endeavors. I eschew regrets, they weigh too much and produce no lift. That said, I regret not recording conversations with the pilots, mechanics, ramp rats, and FBO receptionists I’ve met over the decades while flying to nowhere via routes yet to be determined. All have their stories. Especially you.

There’s far more to John Raymond Barcus than I’ve squeezed inside these few words. Small tribute to an old friend who once bombed Rome.