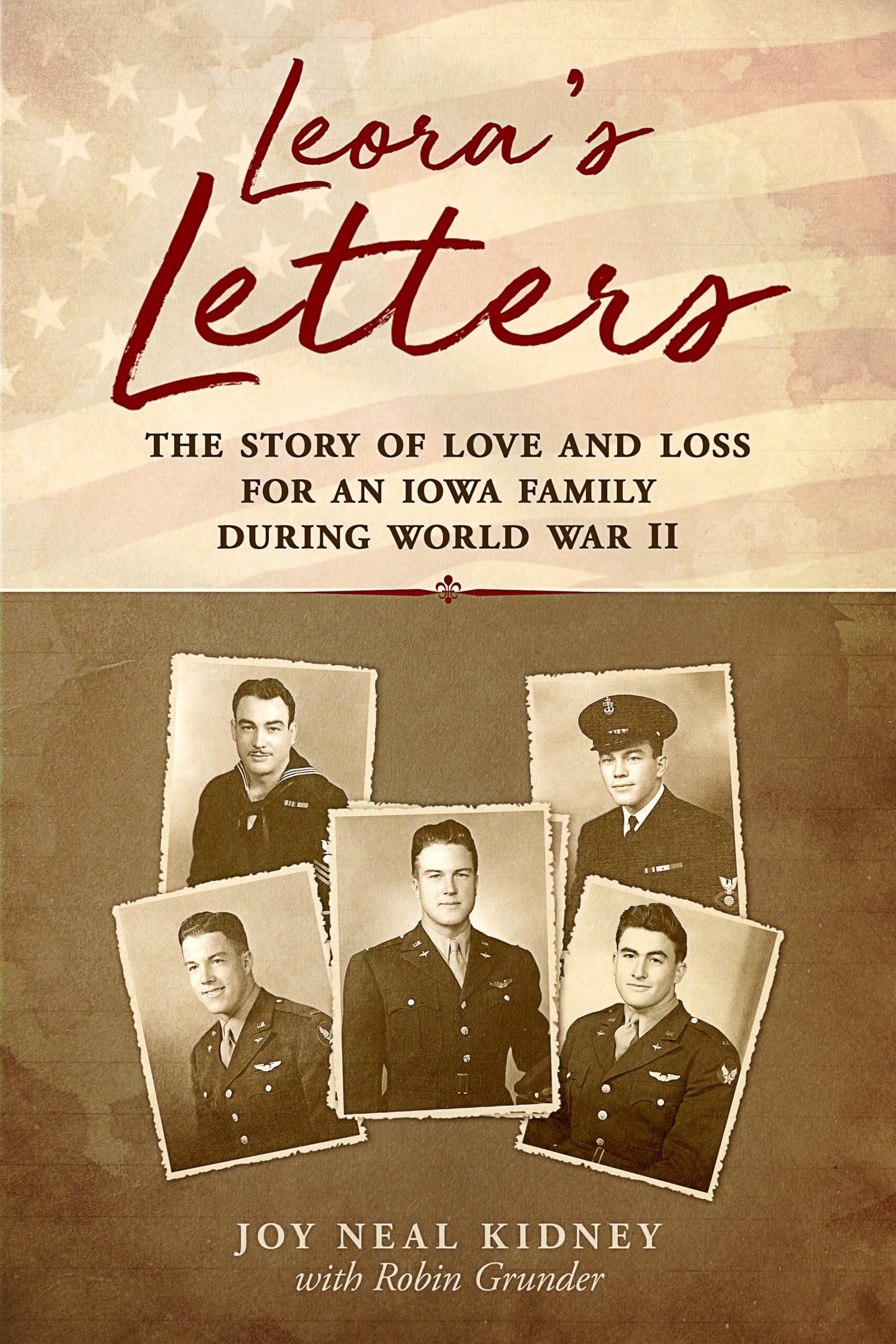

Leora’s Letters

A batch of World War II letters offers a glimpse of the high personal cost of flying bombers and fighters in their intended use.

ATC can be unmercifully dull when no one’s flying. It’s a little like non-combat guard duty in the Army; I pulled a lot of that. The public conjures images of steely eyed sentries at Fort Dix, squinting into the New Jersey mist, M-16s at the ready. Or at least that’s the image I had when reporting for duty there at age 18. In reality, guard duty will suck the esprit from anyone’s corps.

During my inglorious military career, I spent many mind-numbing hours guarding empty buildings from invasion by no one. Similarly, my ATC fantasy poses me as a square-jawed controller intently gazing at a radar sweep, tracking minimally separated airliners. Except, when there’s no air traffic it searches in vain, and while that gets boring, it affords quality time for controllers to catch up on tower gossip.

Thirty-some years ago I was an FAA controller in the Des Moines tower, working an uneventful swing shift with a guy named … Guy, Guy Kidney. His wife’s name is Joy. That’s germane, because on that snowy evening with everything grounded, Guy told me how Joy—this is starting to sound like a shift-before-Christmas story, but it’s not. Instead, Joy was researching her family’s Word War II history, especially accounts of her five uncles. Two had been sailors and three served in the Air Force (Air Corps, then Army Air Force). The brothers scattered to Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, Australia and New Guinea, plus training assignments across the U.S. Joy’s goal was to write a book about their experiences, largely gleaned from boxes of wartime letters to and from her grandmother, Leora Wilson.

Joy’s uncles—Del, Don, Dale, Dan and Claiborne, known as Junior—grew up on a small Iowa farm without indoor plumbing or running water, unless you ran from the well to the kitchen with the pail. Heat was supplied by the wood you cut, split, and stacked, plus the sweat you worked up doing so. By Depression era standards, they weren’t poor; it’s just how rural life was—hard, but they ate well, did their chores, graduated high school and went off to war like millions of other young men and women. All five volunteered. The two older brothers, Del and Don, joined the Navy before the war. Del repeatedly crossed the North Atlantic on oil tankers, which were juicy targets for U-boats. Don was onboard the carrier Yorktown when it was sunk in the Battle of Midway in 1942. Sobering images both. The three younger brothers joined the Air Force as age allowed.

After leaving ATC in 1997, I lost track of Guy and had never met Joy. I forgot her research project, until early in 2020 when she contacted me, saying that her book, Leora’s Letters, was published and asked if I would voice the audiobook version. She knew I did studio voice work and sent me the paperback. Gotta admit, I hesitate to accept unsolicited works. Often, they’re poorly written, but Leora’s Letters had me sitting up in awe of these five brothers, serving in situations most of us can’t fathom.

Anyone with a History Channel exposure to World War II knows how skinny the odds were that all five uncles would survive the war unscathed. I won’t disclose their fates, but their stories make it clear how dangerous flying military hardware—that we civilians admire at airshows—can be, especially in combat. Flying warbirds in peacetime air shows also holds risk far beyond my skill level.

Dale Wilson flew B-25s, Dan P-38s, and Junior P-40s. They trained in Stearman biplanes and the monoplane Vultee Valiant (aka Vibrator) before receiving advanced single-engine training in the North American AT-6, or the twin-engine AT-17 Cessna Bobcat. But that merely lists what they flew. Their letters home to their mother, Leora, tell each young man’s personal story in their own unvarnished, hand-written words.

Who writes letters anymore? We text, tweet, and make snarky comments on Facebook, knowing we’re protected from return fire by cyber fugazis, that are cheap substitutes for courage and duty. In World War II, these brothers wrote home from desert training bases and jungle combat zones, as they struggled to transition from farm boys to pilots ordered to fly to any spot on the planet and do battle with other young men, who probably wrote to their mothers.

I wrote this piece on Dec. 7, 2020, 79 years after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that sent five Wilson brothers off to war. Because there was no internet, they wrote home, and because moms save letters from sons in danger—plus dreaded War Department telegrams—“The secretary of war desires me to express his regret that your son…”—Joy Kidney was able to piece together five moving stories. Can tweets and texts be preserved with the same impact or solemnity? I doubt it.

I learned to fly while stationed in Hawaii and flew my first solo at Wheeler AFB (now AAF) on Dec. 7, 1974, 33 years after the Japanese attacked Oahu. I felt my three landings did more damage to the runway than the Japanese had. Once solo’d, I’d routinely fly to Ford Island at Pearl Harbor for touch-and-go’s. Laps around the pattern took me over the Arizona Memorial, but initially I was too busy being a frazzled student to look down at it with any appreciation.

Then, as I gained confidence and realized I could simultaneously breathe and fly, I looked and saw the ghostly shape of the sunken battleship, tomb to the 1102 sailors and Marines killed that December morning. Whatever hardships I claimed in my young life paled in comparison to those entombed below me and to the sacrifices Leora Wilson’s family made to this country … hell, to the world.

As I recorded the audiobook and reached passages of inevitable grief delivered in War Department telegrams, my voice tensed up, and it took several takes to get through. Leaving the recording booth, I faced the engineer, Steve Mathews—whose father had been a B-25 pilot—and I knew he was choked up, too. It’s powerful stuff.

"Leora’s Letters," by Joy Neal Kidney, is meticulously researched, humbling in delivery, and never dull. Precious is the storyteller who can pull that off. You can find both the print and audio version on Amazon.