SpaceX Pulls A Lunar Lander Out Of The Hat

It’s not so much that SpaceX continues to surprise, but that hardly a week goes by when it doesn’t. And this week, Alice, we’re going to the Moon on a Starship.

In the early days of the space program, a famous quote was attributed to multiple astronauts, but Alan Shepard’s version was the most succinct. When he was asked what he was thinking about sitting atop the fueled Redstone rocket, he replied, “The fact that every part of this ship was built by the lowest bidder.”

The astronaut candidates primed for the next Moon mission—aspirationally planned for 2024—must be thinking the same thing now that SpaceX has been awarded the lowest-bid contract to develop the next lunar lander. They must also be eyeing SpaceX’s impressively consistent record of exploding rockets down in Texas, because that’s the very flight hardware they’ll be riding to the lunar surface. Or at least some version of it.

As we’re reporting, SpaceX was awarded a $2.9 billion contract last week to develop the lunar lander which it proposed to base on its Starship concept that it hopes will fly humans to Mars. The award was, evidently, a surprise given that a year ago, NASA was least impressed with SpaceX’s initial proposal and found it technically wanting. Two other companies—consortiums, really—were awarded more seed money than SpaceX got.

Blue Origin, teamed with Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman and Draper, was given the most at $579 million, with Dynetics, partnered with Sierra Nevada, $253 million. SpaceX got a paltry $135 million. NASA had its reasons. In a report, then-NASA Associate Administrator Steve Jurczyk found that SpaceX’s proposal was developmentally and technically complex and failed to recognize the potential for delays. Besides its astonishing achievements, pyrotechnics notwithstanding, SpaceX and Elon Musk are famous for missed deadlines.

But low bid is low bid and evidently, SpaceX left quite a bit on the table. Blue Origin’s bid was said to be substantially higher and Dynetics' was substantially higher than Blue Origin's. No specific values were reported, other than SpaceX’s winning bid. This not being NASA’s first barbeque on big contracts, it had initially wanted to keep all three companies engaged in a competitive process, but Congress awarded only one quarter of the requested budget, so SpaceX was awarded the sole contract.

During the initial proposal phase, NASA thought Blue Origin’s proposal was the most highly developed and it was thought to have the inside track. What changed, evidently, was that NASA liked the Starship’s capacity to put a lot of weight on the lunar surface—as much as 100 tons—and the agency was impressed with technical progress made on the necessary landing technology. Even if the rockets are reliably blowing up now on landing, NASA probably assumes—rightly—that further developmental work will sort all that out. After all, SpaceX blew up Falcon boosters before it figured out how to land them reliably for reuse. (It has landed 79 and reused 40.)

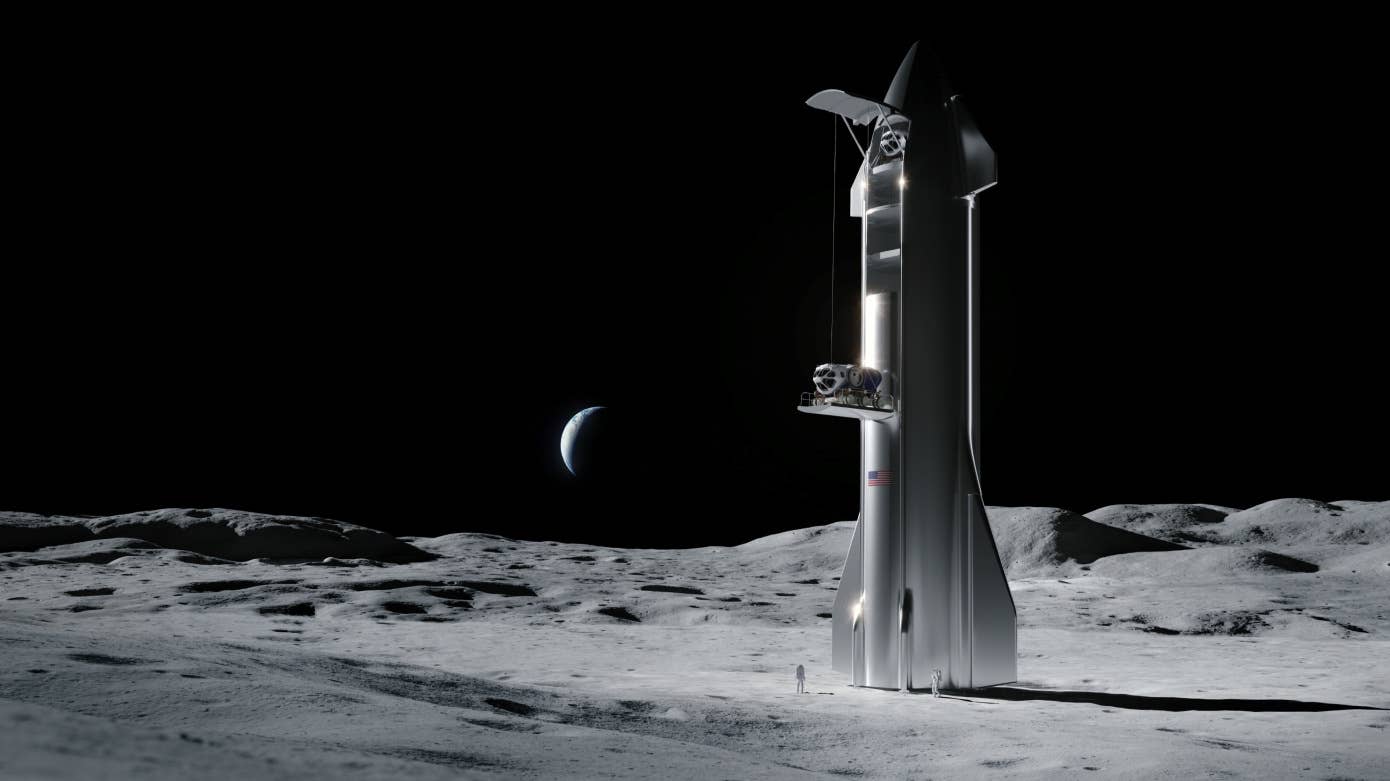

All three companies proposed different approaches to a new lunar landing. Dynetics was kind of an upgraded version of the Apollo-era Lunar Module, with more capacity and reusability. Blue Origin’s Blue Moon was similar, but larger and more modular for flying different kinds of missions. SpaceX’s version is the giant among the three, towering 160 feet high with a 30-foot diameter. (That’s twice the height of Al Shephard’s Redstone and almost six times the diameter.)

The overarching program here is called HLS for Human Landing System and the Moon portion of the project is called Artemis, who was Apollo’s sister and the Greek goddess of the hunt, wilderness and the Moon. (And also of chastity, but I’m not sure how NASA PR will handle that.) The program is designed to put the first woman and the next man on the lunar surface.

Like Apollo, it will use lunar orbit rendezvous, but a little differently. SpaceX’s Starship would be launched ahead of time and a crew would dock, having flown from Earth in the new Orion crew capsule. (Parts actually available.) The Starship would then land on the lunar surface and be capable of launching itself to reverse the trip. With a 100-ton payload capacity, the astronauts can have a pretty ambitious camping trip.

Artemis 1, with the Lockheed-built Orion, is scheduled to launch this year, but it’s not clear that it will. Just as a reminder, the Starship we’ve been watching blow up in Texas is the actual landing vehicle; a version of its technology will be used as the Artemis lander. But eventually, that system will be a super heavy launch vehicle itself. Orion, by the way, is intended to launch on NASA’s new SLS—Space Launch System—whose … parts aren’t yet available. But they’re supposed to be before the end of the year for the unmanned Artemis 1 mission. NASA just had a successful hot fire of the SLS engines.

So the $2.9 billion question is whether SLS, Orion and the Starship can all come together for a mission to the Moon in 2024, as proposed by the Trump administration. If it were the very last day of 2024, that leaves about 43 months. Place your bets. I think it’s doable, but my bet is it won’t happen. The schedule will slip past that at least into the following year, if it isn't canceled altogether.

And judging how Boeing has stumbled with its Starliner crew capsule, I don’t have much confidence that it would bring much to the party to grease things along. The Orion capsule itself has been in development for more than 15 years. Good thing we haven’t been in a hurry. I would love to have been a fly on the wall for NASA’s discussions about awarding the SpaceX sole contract. It could be quite a gamble if it goes south and the other two contractors have gone cold. I’m not sure I would want to own the decision. Then again, sure I would. I’m not worried about my government retirement.

We’ve been talking about a trillion here and a trillion there so often that $2.9 billion seems like a piddling sum for SpaceX’s lander. It’s about the cost of a Virginia-class submarine or a little less than a fifth the price of a Ford-class carrier. But how does it compare to the Apollo-era hardware? Interesting question.

Grumman developed the original Lunar Module with a contact awarded in 1962 for about $350 million. It first flew, manned, in early 1969. Adjusted for inflation—wait for it—that’s about $3 billion in 2021 dollars. I’m sure they’re scratching their heads at Lockheed Martin over how Elon Musk pulled that off.

Of course, he hasn’t yet. But the check is in the mail.