The Making of the World’s Largest Skydive

In early 2006, the world’s most experienced skydivers assembled in Thailand to build a record, 400-way formation. What did it take? The resources of an entire air force, 300 tons of Jet-A, a trainload of oxygen bottles and the determined endurance of a marathon runner. On the 15th anniversary of that record, we’re republishing this article which first appeared in February, 2006.

Photo by Willy Boeykens

In early 2006, the world's most experienced skydivers assembled in Thailand to build a record, 400-way formation. What did it take? The resources of an entire air force, 300 tons of Jet-A, a trainload of oxygen bottles and the determined endurance of a marathon runner. On the 15th anniversary of that record, we’re republishing this article, which first appeared in February 2006.

To those unschooled in the sport — and that is all but the tiniest slice of the dull, normal population — skydivers merely jump from airplanes and gravity does the rest. We’ll concede the gravity part for the moment, but getting out of an airplane with your wits intact is a practiced skill that deserves the more refined term all skydivers prefer: exiting.

Exits are no small thing in skydiving because, just as with landing an airplane, a skydive begun badly can’t always be expected to get much better. So it’s not promising that I find myself inverted in a tangle of bodies 30 feet off the ramp of a C-130, 24,000 feet over Thailand. On the two previous skydives, we had waltzed in order off the ramp in textbook perfection, but clearly there was to be no hat-trick this time.

Not that anyone was surprised. When you’re trying to do that which hasn’t been done before — in this case, breaking the world record for the largest skydiving formation — expecting perfection on the third try borders on the delusional. But as with any other sport, perfection that eludes the first attempt yields to practice, repetition and sheer gritty determination.

All of that was available in abundance in late January and early February 2006, as 440 of the world’s best, large-formation skydivers — the fifth iteration of The World Team — converged in Udon Thani, Thailand, to better the previous record of 357 persons, set in Takhli, Thailand, in 2004. The Thai government and Royal Thai Air Force (RTAF) had generously agreed to provide the aircraft and resources in conjunction with the 60th anniversary of the rule of the country’s revered King Bhumibol Adulyadej.

Why Do This?

In sport parachuting, world records aren’t exactly there for the plucking, but many skydivers on the regular “big way” skydiving circuit — that’s probably 600 or 700 people worldwide — can claim some sort of record dive and have the T-shirt to prove it. In skydiving, as in aviation, record jumps attract because they leaven the otherwise mundane with an exotic, competitive flavor.

Not that there’s anything mundane about a 100-person formation, but skydives of that size happen four or five times a year and some skydivers find in them an unavoidable, plodding ordinariness. They are frequently hours of boredom in the hot sun, “dirt diving” the same plan over and over, long climbs to altitude with a cannula stuck up your nose, punctuated by two or three adrenaline-filled minutes, followed by tedious video debriefs.

Skydivers are attracted to record dives for the very reason that the biggest, the smallest, the fastest, the most or the first of everything is anything but ordinary. The ragged edge of the envelope, even in politics, is always more interesting than the safe middle. And in skydiving, it doesn’t take Steve Fossett’s checkbook to reach for a world record. Anyone with skill, time — both in the sport and to practice — and a reasonable amount of money has a shot.

World Team 2006 is very much a slice of every walk of life, from mechanics, to doctors, to lawyers, to airline pilots to self-made entrepreneurs. In the esoteric world of skydiving, record dive opportunities happen often enough to loom momentarily large only to fade when the next attempt presents itself.

There are state records, multiple-formation records, women’s records; the list is long. But the World Team’s efforts, dating to 1994, have proven to be the records that matter simply because they attract only the very best in the sport and everyone realizes how difficult they are to achieve. It’s not so much that the skydiving is demanding, although it is, but that it requires the resources of a small air force to muster the lift and a staggering volume of behind-the-scenes organizational work requiring months of attention.

And here, a fine-point digression about records: Like baseball milestones, two of the World Team’s ever-larger record attempts carry cautionary asterisks. In 1994, the first World Team set the unofficial formation record at 216 persons in Bratislava, Slovakia. Two years later, another World Team raised the record to 297 in Anapa, Russia. Other non-World Team groups also added rungs to the ladder in the interim.

To be certified as an official record by the Federation Aronautique Internationale (FAI), a skydive has to transpire exactly as the organizers said it would, with all the grips taken and the slots filled correctly. If anyone is missing or the build is incorrect, no official record is granted, but a Guinness Book entry instead.

There’s no denying that this is a kiss-your-sister second placer, but the disappointment seems to fade with time and the next record opportunity. I have never heard veterans of previous World Team efforts complain about falling short of an official record. That’s because in the end, a large skydive attempt is just a team sport, like basketball, hockey or baseball. It just happens to be practiced at the extreme apogee of the possible by the largest teams ever assembled for a single purpose; and in order to succeed, every player must achieve perfection.

In the broad scheme of life on earth, 400 people falling through the same column of air for two minutes has little lasting significance outside the self-absorption of the sport itself. But what it takes to get them there, shape them into an effective team and coax 400 individual moving parts into one shining moment of perfect performance is a story as worthy as that of any Super Bowl team that ever took the field.

Why Thailand?

The Thai government — including the country’s royal family — are uniquely interested in skydiving. Even though the sport enjoys little commercial profile in Thailand, it’s woven into the country’s fabric in a way unique in Asia. This is due in no small measure to the World Team’s visionary founder, longtime skydiver and organizer BJ Worth, his wife Bobbie and Larry Henderson, whose contacts and knowledge of Thai culture through family missionary work in Asia have proven invaluable.

To the people of Thailand, this is very much a Thai record and they are distinctly honored to make it possible. While we were waiting for one of the first declared 400-way attempts to reach jump altitude, Air Marshal Bunchuay Supbornsug told me the RTAF was able to commit such considerable resources to the 400-way project because of the once-in-a-lifetime juxtaposition of the King’s 60th anniversary jubilee and the wherewithal of Worth’s considerable organizational talents to make a skydive of this size.

The latter could not exist without the former. Air Marshall Bunchauy explained that for Thailand, the record represents a priceless opportunity to place Thailand’s culture and modern, forward-looking outlook squarely upon the world stage. He believes the payoff in prestige and future tourism will more than offset the investment.

Following our conversation, I found myself wondering why other countries with greater resources than Thailand don’t muster the same kind of philosophy to advance their own interests in creative ways, combining military assets with civilian activities. The entire city of Udon Thani, which has about 95,000 inhabitants and is located 270 miles north of Bangkok near the Lao border, lent its enthusiastic support to World Team 2006.

The RTAF Wing 23 Airbase was the perfect staging point for the five C-130s and large landing field we would need to achieve the record. If you flew during the Vietnam war or had a relative who did, you’ll remember Udon Thani as Udorn. As I walked the airbase’s long runways after my landings, I couldn’t help but think of the many U.S. fighter pilots who flew their last missions out of this base. The ghosts of U.S. presence are everywhere.

Who Does This?

Speaking of fighter pilots, skydivers share with them a take-no-prisoners sense of humor and the older they get, the more ruthless they seem to be. Every year I hear more tasteless jokes about Depends and trying to get walkers jammed through the aircraft doors. Despite the rigors of jumping out of airplanes and landing fast parachutes, this is by no means a young crowd.

Some of these skydivers entered the sport in the 1960s and 1970s — when, as the current bumper sticker joke has it, skydiving was dangerous and sex wasn’t. The average age for this year’s World Team is 42; the oldest is 65, the youngest 20.

These are among the most experienced skydivers in the world, with more than 30 countries represented and the average number of jumps is about 4800, much of them in large formation attempts. One of the most remarkable aspects of this event is how determined some of its participants are.

Nearly 150 of the World Team’s members are from the U.S., where it is relatively straightforward to stay current and trained in the skills necessary to build large formations. It’s not quite so easy for a skydiver from Japan or Finland or even Thailand, countries where the general aviation activity necessary to support skydiving is either minimal or non-existent. Yet all of those countries are represented on the World Team.

Speaking of skills, although most people unfamiliar with it don’t know this, skydiving is not just falling out of airplanes. It has sub-disciplines, each with its own set of skill requirements. For instance, four-way competitive skydiving requires building as many specified formations as possible within a 35-second window — the proverbial knife fight in a phone booth. By contrast, in large-formation skydives, the essential skill is a high-speed gliding dive to a moving spot in the sky, followed by a graceful stop and a few feet of careful maneuvering.

The maneuvering may be around dozens of other skydivers angling to the same moving point 300 or 1000 feet away. It’s kind of like driving your car through freeway traffic at 120 MPH and stopping in your garage without taking out the back wall. Some of the World Team’s skydivers are big-way connoisseurs and participate only in that discipline, some do both four-way and eight-way competitive skydiving and some are accomplished in other aspects of the sport.

Although there are many professional skydivers on the World Team, it’s composed primarily of talented weekend skydivers with a passion for the sport. All are here in Thailand by invitation only, having passed review by a selection committee. I’m a last-minute addition to the team, occupying a bench slot along with 40 others, standing by in case of injury, illness or other calamities. (Those things happen and as in other team sports, you can’t play the game without a full roster.)

The Lift

Even before we arrived in Thailand, the Royal Thai Air Force had been training in the delicate art of flying large transports in close formation at high altitude, something that isn’t routinely done, if it has been done at all. For 400 skydivers, plus 15 camera flyers to video the formation for record confirmation, the RTAF committed no fewer than five C-130s, a level of support few of us can conceive being possible anywhere but in Thailand.

For contingencies, the RTAF positioned seven C-130s at Udorn, more than half of its available fleet. Moreover, because the RTAF allows its crews only one sortie per day when flying unpressurized above 18,000 feet, every Hercules crew in the air force had been assigned to the World Team effort. For their part, the RTAF pilots had bitten off a demanding task.

Once out of the airplane, skydivers can translate only so far in the sky to build formations. A skydiver in freefall is a lifting body with a definite but limited glide ratio. Given the number of skydivers in this group and the size of the five-airplane formation, the sort of formation military pilots fly for tactical training drops wouldn’t work. It’s not so much that the formations have to be tight, although they do, but that they need to be consistent.

In our early training jumps leading up to the final record, many of us noticed that the “exit picture,” that is, our post-exit relationship to where the skydiving formation would be when we got to it, was never the same twice. This, perhaps more than any other single factor, is why large skydiving formations rarely complete on the first try, or the second, or the third.

Imagine 400 airplanes approaching the same airport, from nearly the same altitude and speed. Now think about the airport moving and the pilots being slightly hypoxic and stoked on enough adrenaline to revive the dead. Did I mention there are no controllers for sequencing and separation?

This leads to rushing — overamping we call it — and mid-air collisions; sometimes a lot of mid-air collisions. These are rarely violent enough to cause injury, but if two skydivers in mid-dive tangle close to the formation, the resulting instability can knock both of them below the lowest flyable glidepath, making it impossible to reach the formation.

Even with no collisions, early in a big way event like this, there’s a tendency to overdive on a moving formation, whizzing by it like a missed freeway exit. This is known as “going low;” it’s often unrecoverable and it’s the kiss of death in big skydiving formation work. As daunting as just holding a perfect five-ship aircraft formation is, consider this: as 80 or more fully equipped skydivers charge the ramp on exit, 17,000 pounds worth of payload shifts the CG aft in about six or seven seconds. Think you might notice that from the left seat? Ever practical, the Thai’s clever solution to this was a couple of tons of bagged rice stacked against the forward cargo compartment bulkhead.

Rare Air

A big sky dive like this needs 100 seconds, at least, of working time and the only way to get it is to climb to high altitude — very high altitude. We started workups from 20,000 feet and moved incrementally to 23,000, 24,000 and, eventually, 25,400 feet for the final two record dives.

Garden-variety weekend skydives are made from 13,500 feet; thus they don’t require supplemental oxygen. Routine, stateside, big-way skydives are from 17,500 feet or perhaps up to 20,000 feet and the aircraft flying them are fitted with oxygen systems best described as lash-ups. They work well enough but not necessarily well.

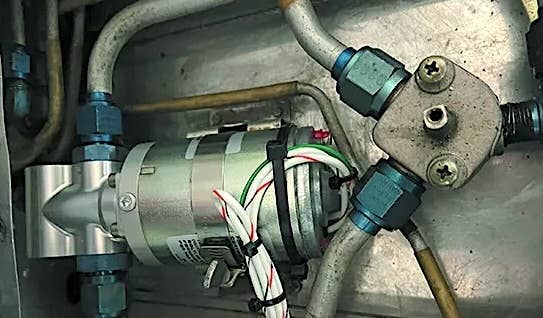

Hypoxia-wise, there’s a yawning gap between 17,500 and 24,000 feet; it’s the difference between a little light-headedness and stone-cold stupid hypoxia. In the RTAF C-130s, the oxygen system, devised by skydiver Dr. Ben Massey, is both clever and effective. It has heavy-walled hose manifolds the length of the cargo bay attached with sliding, tie-wrap rings to the cables paratroopers use to anchor static lines.

The hose has a series of pressure-reduction fittings into which each skydiver plugs a hose, either for a cannula or just to insert into a full-face skydiving helmet. As the skydivers shuffle to the ramp for exit, they slip the supply hose along the static line so they can remain on oxygen until the last second. The system is charged by three bottles of the size used for welding rigs, with a fourth in reserve.

For every single, five-ship skydive, 15 industrial bottles of oxygen were consumed, along with about 5000 gallons of Jet-A. High altitude yields another side effect skydivers must contend with: high true airspeeds, both for the aircraft and the skydivers themselves. Skydivers are accustomed to exit speeds in the 80- to 90-knot indicated range, which — at 13,500 feet — works out to a TAS of perhaps 110 knots. At that speed, you clear the exit door, grab some air and start to skydive.

At 24,000 feet, the air grabs you. The C-130s indicate between 125 and 130 knots, for a true of up to 190 knots or 218 MPH. Veteran Swedish skydiver Sven Mortberg, who has years of experience organizing skydiving events using the Swedish military’s C-130s — briefed us on the safest way to exit without injury: Hold the elbows tightly inboard with the hands crossed in front of the helmet visor.

Oxygen bottles, plus spares. That's two tons of rice for weight balance on exits.

This, he reckons, protects the shoulders against the wrenching impact of tangling with another skydiver if he (or you) goes momentarily (and violently) unstable out the door. Because of high-speed exits, dislocated shoulders are a common C-130 exit injury, but there were far fewer of them this year than in 2004, when the World Team set the previous record.

Dialing In

There’s no question that C-130 exits are an attention getter. At 190-knots, the air is cold and palpable — “brutal” is the world Mortberg used. To me, the get-outs felt more like cannon shots than exits, but in a second or less, you’re out of it and in clear air, surprisingly alone in a cold sky. Once in the air, the belly-to-earth fall rate is also much faster in the flight levels — probably approaching 200 MPH, versus 120 MPH in denser air. Long dives from the exit to the formation — 15 or 20 seconds in length, sometimes longer — probably yielded true airspeeds of 250 MPH or more.

As the week progressed, RTAF pilots improved the aircraft formation incrementally, even as the skydivers were refining the all-critical approach into their individual slots in the skydive. This is an especially remarkable achievement for the RTAF, given that they changed crews with each sortie and five-ship formations have no place in their routine mission profiles.

The skydiving formation designed for World Team 2006 is pretty, but pretty is only part of it. If each skydiver is a lifting body, the entire formation is an enormous, biomimetic Frisbee whose aerodynamic characteristics can’t be modeled in the wind tunnel. The thing has to fly right, otherwise there’s no hope of building it.

Big-way skydivers have to contend with myriad challenges, but at the top of the list is fall rate and — within reason — the faster it is, the better. A vertical speed of 125 MPH is close to the ideal, but 120 MPH will do. If it slows to 115 MPH or less, the difficulties compound themselves.

If every skydiver in the world were 5-feet 8-inches tall and 155 pounds, any fall rate might do. But individual skydivers have different fall-rate ranges based on size, body shape and weight — a small, light person can vary his or her rate between perhaps 100 MPH and 115 MPH comfortably. Adding lead weights in a belt or vest will widen that range toward the faster end — as little as a couple of pounds or as much as 20 or 30 pounds.

I saw one World Team member with 18 pounds of lead. I can tell you with confidence that a 45-year-old, weekend skydiver with a pot belly won’t be mistaken for a ballerina, so loose suits, floppy sleeves, swoop wings under the arms or webbed gloves were in evidence. These extend a heavier skydiver’s fall rate range a few MPH toward the slow end.

All of this sounds tidy in theory, but it’s not simple in practice, since you have to guess at the fall rate and ballast up or add drag before the skydive and hope you guessed right. Being too heavy is just as bad as being too light; you’ll either float above or sink out the formation.

The formation itself — a core 70 “blot” with arcing “wackers” attached — is specifically designed to fall and build fast but, more important, to self-stabilize. Wackers, which are named after the business-end of the weed-chopping machine, contribute to inherent stability because they damp variable-fall-rate-induced waves that stress large formations.

It’s not an exaggeration to think of a large skydiving formation as a house of cards held together with a few critical grips; the aerodynamic forces involved are substantial. We began the week with smaller formations, to give the wacker elements target practice in building those shapes.

The formation sizes steadily increased through 112s, 220s, 360s and eventually the first 400-way attempt. The early work-up dives proved so chaotic at times that the casual observer might conclude that that this rabble would be lucky to nail 10 skydivers together, never mind 400.

But it’s always that way with these things. Practice yields results and by the fifth declared 400-way attempt, you could see the formation trying to break out of the noise, like a photograph in the developer tray. (Remember those?) On jump eight, it built perfectly, but the last grip taken on the outside coincided with the first grip broken on the inside to signal the breakoff at 7500 feet.

Then something remarkable happened. In big-way skydiving, it’s common for jumps to regress in quality — one step forward and two steps back is something skydivers know all about. But not this team. Two hours later, from 25,400 feet, it built the same, perfect 400-way and held it for 4.3 seconds; a new world record.

Watching through binoculars from the ground, I realized I was looking at the best large-formation skydiving group ever assembled and perhaps one of the most remarkable, rapid, team-building efforts in any sport. Unlike in previous years, where the team struggled until the last possible opportunity to achieve the record, this team did it a day early and could have gone up and repeated the feat.

I wondered if organizer BJ Worth shared the view. ”I do, absolutely,” he told me after the event. “On the first jump of the day, dive seven, we proved to ourselves that we could do this. People got very focused, got in the zone and started to work together as a team in a way that’s very rare. I’ve never seen it before.”

And to what did he attribute this? “I think a lot of this world record is psychological. The skydiving tasks for each person are not that difficult. I think at first a lot of people had a hard time believing we were really going to be able to do it, and then they saw that it was possible, that it really could be there.”

Even before the last rig had been packed in Udorn, the logical question arose: Is 500 next or have we reached the limits of the possible? “We’re near what is practically possible,” Worth says. Larger formations would need more working time, which translates to more altitude and the current oxygen technology is already pushed to its limits. Bail-out bottles have been contemplated but expense and training could be showstoppers.

“In my heart, I would love to have World Team go up and do 440 or 450, but 500 is probably too much of a leap, only because of aircraft support. It would take six aircraft to do 500 … I don’t think it’s possible that we’ll get that kind of support.”

On the other hand, when the 100-way record fell in 1986 and 200 in 1992, skydivers thought they were witnessing the zenith of the big way, the glorious end of an era. At the time, BJ Worth thought otherwise. He might again.