Is A 406 ELT Worth It? Reduce Expectations

Every other summer, I torture myself with the $1500 biennial ELT switch flip. I install the required 24-month battery, wait for the minute hand to sweep past the top of…

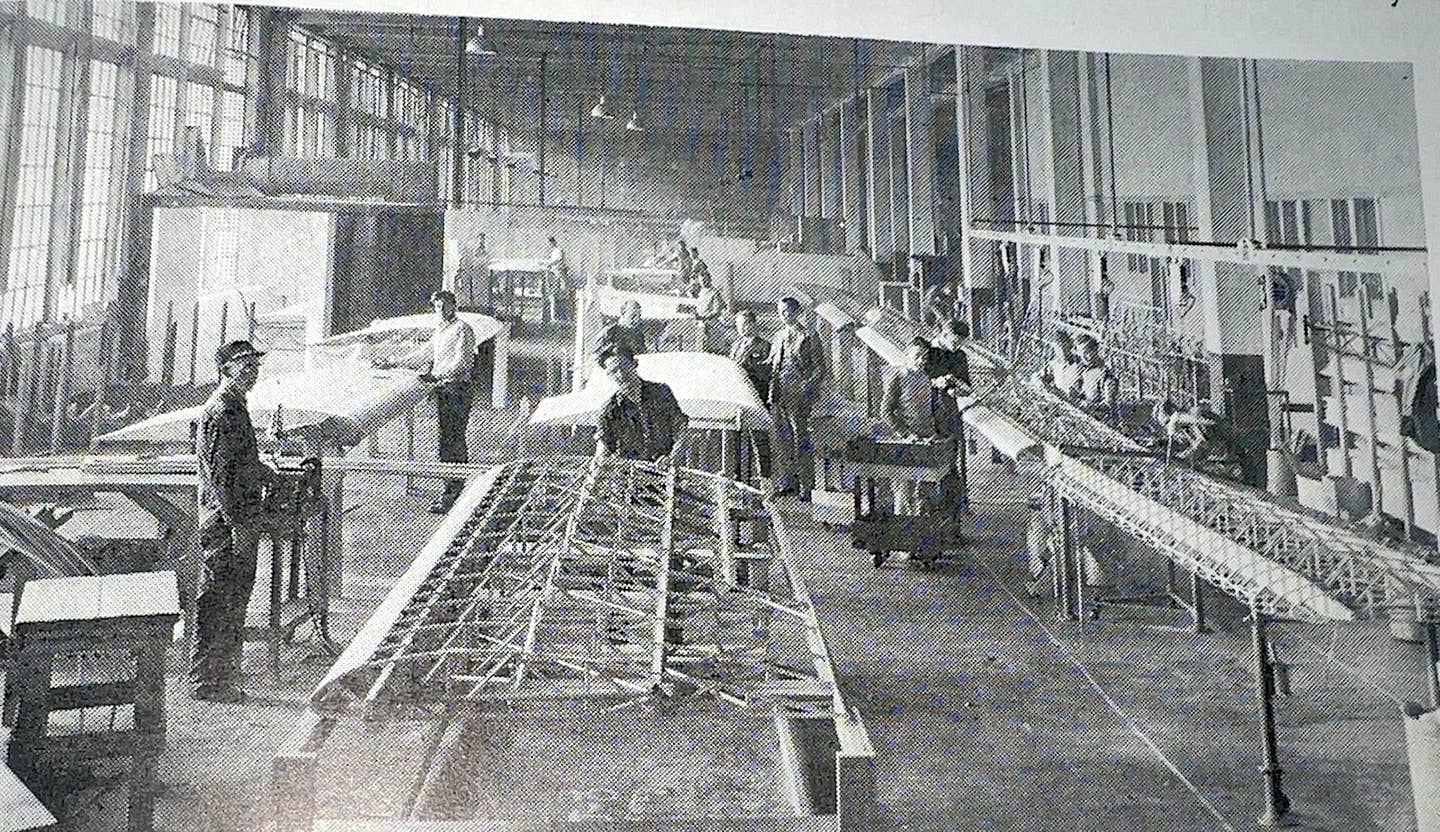

The Cessna 172 in the accident above was equipped with a 121.5 MHz beacon. It activated on impact, but didn’t aid in locating the airplane. One occupant was killed, one survived after a night in the woods.

Every other summer, I torture myself with the $1500 biennial ELT switch flip. I install the required 24-month battery, wait for the minute hand to sweep past the top of the hour and press the test switch with bated breath. The crisp woop-woop of the truly ancient EBC 121.5 MHz beacon makes the Cub legal for two more years. But one day, the dreaded decision will come. I’ll have to buy a 406 MHz ELT.

That’s slightly complicated in the Cub because of the extra effort of siting an antenna on a rag fuselage. But for all the money thrown at it, it will at least be more likely to actually function in the event of crash. Or will it? To find out, I recently pored over the crash reports of 406 MHz-equipped airplanes and while it’s true they work better when they work, they get smashed in crashes just as often as the older beacons do and fail to activate for reasons that aren’t always clear.

One downside of ELTs in general and especially 406 MHz models is a staggeringly large number of false alerts—more than 11,000 a year, plus another nearly 7000 false alerts from marine and terrestrial units. Most have to be patiently tracked down by rescue agencies.

Increasingly, as rescue and location aids, ELTs are being displaced by ADS-B, radar and cellphone searches, making their value less impressive. Still, under ideal conditions, a 406 MHz ELT, or a portable locator beacon, will summon help faster than anything short of a 911 call.

How We Got Here

On paper, the emergency locator transmitter is a stunningly great idea: Airplane crashes, transmitter goes off and soon the pararescue person is fast roping in to tend to the survivors. Or at least the victims can be readily found. Or so it was supposed to be following the 1973 FAA regulation mandating 121.5 MHz ELTs after the disappearance of a chartered Cessna 310 carrying two congressmen—Hale Boggs and Nick Begich—in Alaska. Despite a 39-day search, no trace of the airplane was ever found.

General aviation groups then—and now—supported voluntary ELT installation but opposed the mandate. Field experience with ELTs hasn’t burnished the idea much. While 121.5 MHz beacons clearly saved lives, a high false-alarm rate—as much as 97 percent—and a low crash-activation rate made owners dubious of their value. A NASA study of early ELT technology found that many did not operate within the specified design thresholds and laboratory impact performance produced erratic results.

In 2011, Embry-Riddle researcher Ajit Jesudoss set out to find out how often ELTs of either type aided in finding accident sites by reviewing NTSB reports between 2006 and 2010. His research was hobbled by sketchy NTSB reports that don’t reveal if the ELT helped locate the wreckage. Of 81 cases with usable data, 31 percent aided in locating the accident, 58 percent did not; the rest were indeterminate. My own sweep of recent accident data was also frustrated by sketchy details. I reviewed five years of accident data between 2013 and 2017, with a keyword search for ELT. For 2017 alone, I bored into the details of 100 randomly selected accidents from 1328 U.S. crashes in the NTSB files.

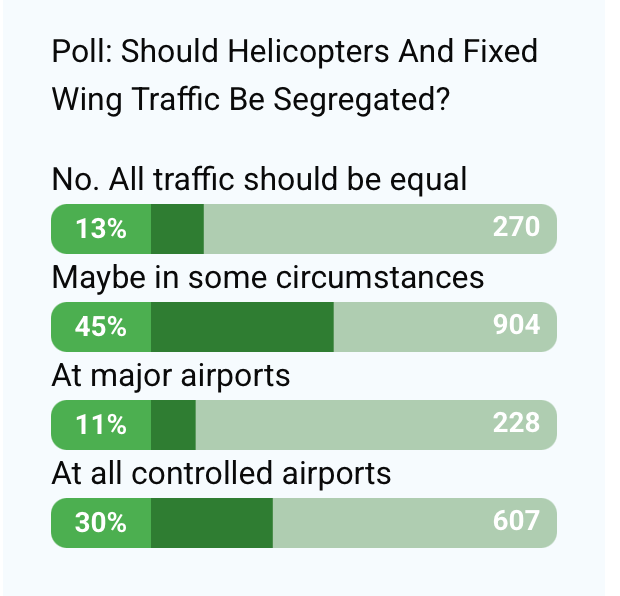

In the accidents where the data appeared reliable, I found results similar to Jesudoss’ findings. For 121.5 MHz beacons, about 41 percent aided in finding the crash while 59 percent did not. Newer 406 MHz beacons did a little better, but not much: 43 percent aided, 57 percent did not. In 26 of the 81 accidents I reviewed, the report either didn’t say what type of ELT was aboard or whether it aided in location. My dive into the 2017 data revealed even lower positive trends for both types of ELTs, as shown in the graph at right.

As for beacon activation irrespective of whether it actually aided in crash location, on the whole for both types, they worked as intended in about 54 percent of the accidents, but failed in 42 percent. The rest were unknown. When the beacons are sorted, the numbers get too small to make definitive conclusions, but using the 2017 data, the 121.5 MHz models fi red as intended in 38 percent of the accidents, the 406 MHz beacons a bit better at 50 percent.

This is a glass-half-full/half-empty sort of dilemma. But basically, these devices activate as intended half the time or a little more and actually assist in locating the accident site, at best, in a little more than a third of the accidents. I’d call that mediocre performance, but with one bright spot: If a 406 MHz ELT works like it’s supposed to, the cavalry is just over the hill. Researchers Ryan Wallace and Todd Hubbard in an Embry-Riddle-published report found that in 139 missions reviewed, the mean search duration for 121.5 MHz beacons was 14.2 hours, 11.8 hours for 406 models, but only two hours for 406 beacons equipped with GPS position input. (Not all are.)

False Alarms

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which oversees the U.S. share of the COSPAS-SARSAT satellite system that monitors the globe for 406 MHz distress signals, reports that 98.6 percent of aviation alerts are false alarms. When marine and terrestrial beacons are added, it was 19,295 alerts in 2019 or about 52 a day 24/7. Can that possibly be right?

It is right, according to Lt. Col. Matthew Mustain, who’s ops director at the Air Force’s Rescue Coordination Center at Tyndall Air Force Base in Florida. The day I spoke with him in mid-July 2020, five controllers there had chased down 48 alerts the previous day. To be fair, more than 5000 of those yearly falses are single-pass blips whose source is never determined, probably caused by the odd fumble-fingered person accidently firing a 406 beacon. Nonetheless, AFRCC does a lot of wild goose chases.

“We spend a ton of time on the phone doing detective work,” Mustain told me. Another bright spot is that 406 MHz beacons are registered—or are supposed to be— so often a single phone call to an owner resolves the false.

“As you can imagine, these huge numbers take away from working cases where there’s actually a mishap or someone is in distress,” Mustain adds. Cases get difficult when the beacon is unregistered or the phones aren’t answered. Then it requires N-number lookups, FBO and airport manager calls or whatever it takes to find and silence the beacon.

Because the 406 system resolves position quickly and accurately, many of the non-distress activations are tracked to airports, the result of bungling maintenance or a hard landing. “But if it’s on a ridgeline in West Virginia or the middle of the West Texas desert, that’s when the ice water goes down your back. That’s probably not a false alert,” says Mustain, who came up in the GA ranks and flew 10 years as a combat rescue pilot in the Air Force.

“A big piece of what we do is education. When I get a pilot on the line, I say, sir, could you please register your beacon. This is one message I want to get across to people. Make sure your 406 beacon is registered. It makes our job so much easier if you’re up to date,” Mustain says.

When the 406 system works at its best, location and rescue can be impressively quick. I found one Alaska accident in which the Coast Guard was on the scene while the wreckage was still burning and another with a response time of about two minutes. On the whole, however, cases in which the 406 ELT resolved a life-or-death rescue aren’t common. Most crashes are near airports and even when they aren’t, the beacon is definitive in the outcome only rarely and aids location finding just short of half the time.

Lt. Col. Mustain reports that despite the profusion of false alerts, 406 signals are resolved much more quickly than 121.5 alerts ever were, often in single-digit minutes.

Finding You

While the Coast Guard handles coastwise and interior Alaska SAR cases, the Civil Air Patrol and local law enforcement do the heavy lifting in the continental U.S. And yes, they still spend a lot of time chasing false alerts on the ground with the same direction-finding equipment they’ve been using for years. CAP, says operations director John Desmarais, has undergone a significant revolution in the way it does business. “We used to do 1200 to 1500 missions a year. Last year, we had 865 missions. When you look at them, only 330 were ELT missions. It used to be 900 a year-plus for ELT missions,” he says.

When Desmarais joined CAP in 1987, the organization flew 20,000 SAR hours a year; last year, it flew fewer than 2000. Increasingly, radar, ADS-B and cellphone tracking carry more of the weight on searches. Does that mean the ELT is less of a player than it once was?

“It is. It’s helpful in some cases, but to be honest with you, the vast majority of the missing aircraft cases are going to get resolved with cellphone and radar data. The best recommendation I would give is to fi le a flight plan, making sure the cellphone data is available for the pilot contact info. And some of it’s old school. Let people know where you’re going. Or if you’re changing your plans,” Desmarais says.

That’s not to suggest that 121.5 beacons are as good as 406 models. The 406s are easier to track and it’s often done from AFRCC at Tyndall, vastly reducing search time. “I can remember in the old days, we had missing aircraft searches that went on for weeks. These days, if we have a missing search that goes longer than a day, I’m really surprised,” he adds.

In 2009, COSPAS-SARSAT stopped monitoring 121.5 MHz transmitters, but many pilots monitor guard on a second radio and report signals to ATC. FAA facilities also monitor the frequency. CAP can start a search from these reports.

CAP’s cellphone forensics unit— about 10 people—is kept busy with both missing persons and missing aircraft searches. Local law enforcement taps into CAP’s capabilities because they don’t do enough cell tracking to be proficient at it. Another 14 people are tasked with radar searches and increasingly, that’s ADS-B.

“The ADS-B data has been very helpful for a lot of it. Pulling the data together, we’ve got some incredibly smart guys who work this data behind the scenes. And it’s not just the radar data and the ADS-B data, we’re looking at the weather patterns, we’re looking at data on the airplane. If we know that the airplane had a few sorties that day, we look to see how it flew earlier that day. That helps a lot. Storing the data, we can go back a couple of weeks,” Desmarais says. That means if the beacon doesn’t work—and the data shows it often does not—CAP has a starting place it never had before.

Is A 406 Worth It?

That’s now the thousand-dollar question. To be blunt about it, the entire ELT idea never worked very well. The beacons fired when you didn’t want them to and failed when you did. It’s debatable whether 406 MHz has improved this much. They still fail to activate in nearly half the crashes, which is only a little better than 121.5 MHz beacons performed.

Given the mediocre performance against cost, I could make the argument that ELTs were never well suited for aircraft in the first place because of technological limitations and thus the mandate has, as AOPA always argued, been an undue burden on owners. They activate for unknown reasons, get jostled during maintenance and have proven tender in crashes.

Current 406 MHz ELTs false alarm at a rate four times greater than their marine cousins, EPIRBS, and 13 times greater than PLBs, which are just as easily located in searches. AFRCC’s Mustain says that’s because a PLB requires a deliberate open-the-case-extend-antenna action to activate it; an ELT is designed to fire on its own.

With all this in mind, if you’re nursing along an old 121.5 MHz beacon, as I am, are you placing yourself at risk? The data suggests not much. At best, they help locate the crash in half of cases, but my sweep of 2017 data revealed it was more like one in six or seven. In other words, the crash was found by other means.

ELTs were rarely big players in life-and-death rescues and they still aren’t, although it happens from time to time. Being trapped in the wreckage injured and disabled is a pilot’s worst nightmare. It just doesn’t happen very often.

If that is a worry, a 406 beacon may assuage it. A little. A better solution might be to carry a $300 PLB that you can also use while hiking, fishing, boating or off-roading. Or, if you’re really a worry wart, an active satellite tracker like the Spot or Spidertracks, which are more effective yet. The exception I’d make is if I flew in Alaska or the mountain west, where the 406 might add a measure of risk reduction worthy of its cost. Still, for the money spent, don’t expect too much of it.

In my view, the best argument for a 406 ELT is to reduce the stress and strain on Lt. Col. Mustain’s troops and the CAP in tracking down false alerts. If it’s a real distress case, they’ll find you just as quickly with a PLB costing a quarter what an ELT does without the periodic battery replacement.

If you’re spending the money on a 406 MHz ELT, spend a little more to get the GPS datastream into it and don’t forget to register or re-register if the airplane changes hands.

An Unblinking Satellite Net

As a technological marvel, the COSPAS-SARSAT satellite system is right up there with GPS. It was conceived in 1979 by the U.S., Canada, France and the former Soviet Union. Today, 45 countries are signed on to support it.

In all, 55 satellites carry COSPASSARSAT receiving and processing packages. Recent additions include a network of so-called MEOSARs for medium earth-orbit satellites. NOAA operates the U.S. space segment and forwards received 406 MHz alerts to the Air Force's Rescue Coordination Center or the U.S. Coast Guard.

With so many satellite passes available, says Air Force Rescue Center's Lt. Col. Matthew Mustain, ELT positions are resolved quickly through triangulated azimuth calculations. That helps with chasing down thousands of false alerts, but registering the beacon and keeping it up to date helps more.

Yet even though this is required by law, many owners forget it or skip it. To register, use NOAA's website: www.sarsat.noaa.gov/beacon.html. You can contact NOAA by phone at 301-817-4576 and report a known false alert to Flight Service or NOAA.

This article originally appeared in the September 2020 issue of Aviation Consumer magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to Aviation Consumer!