LSA or Legacy? Costs Compared

When the light sport aircraft idea first broke ground 20 years ago, the idea was a new class of airplanes bridging between so-called “fat ultralights” and standard-category airplanes whose inflated…

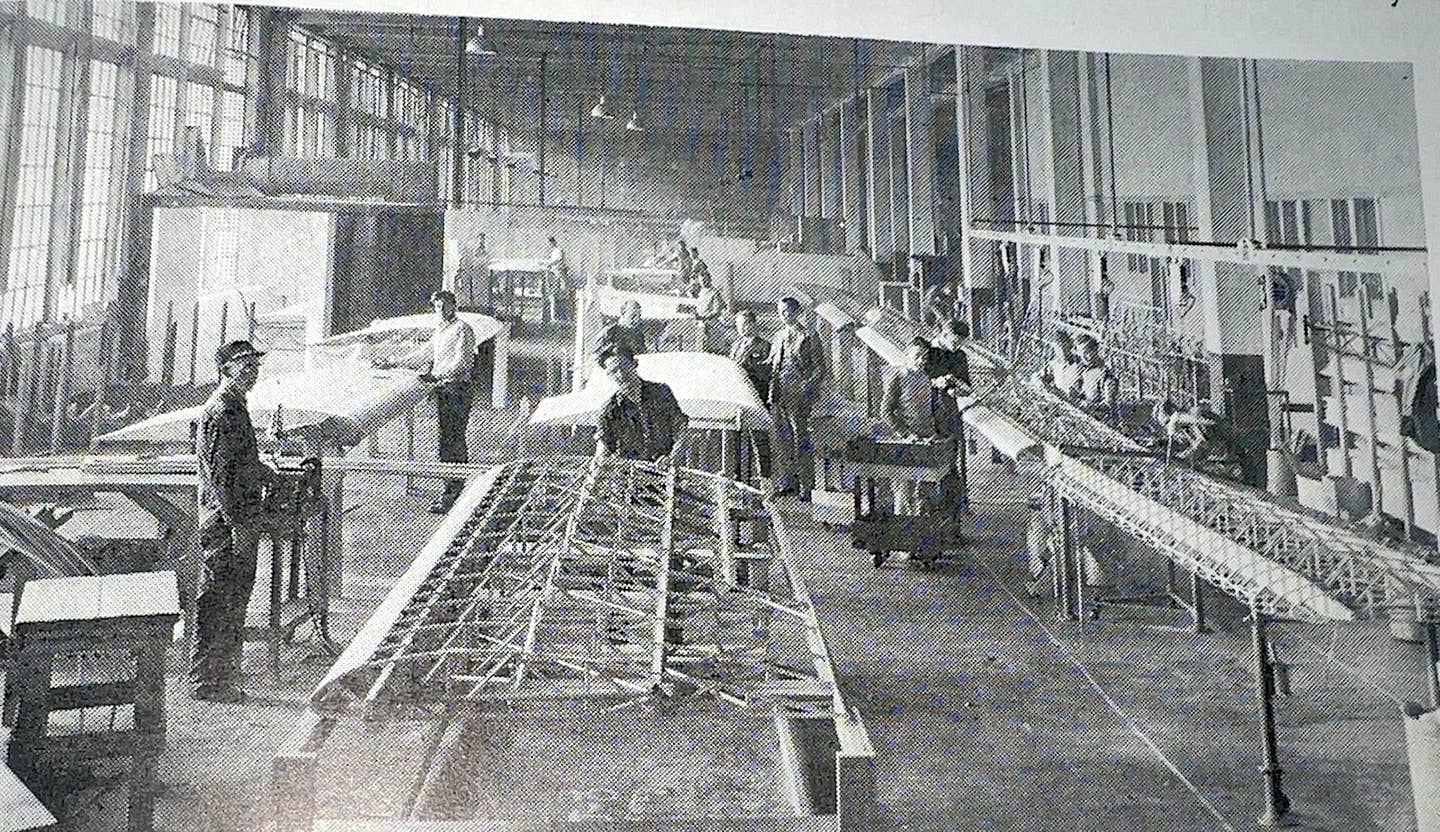

South African owner Kai Neckel’s Flight Design CTSW. “Amazing overall package…great cruise and very roomy. Excellent useful load.”

When the light sport aircraft idea first broke ground 20 years ago, the idea was a new class of airplanes bridging between so-called “fat ultralights” and standard-category airplanes whose inflated prices made them unaffordable save for the wealthy few. Two decades later, has the experiment paid off?

Yes, but with some qualifications. Light sport airplanes were supposed to be simpler to build and certify— they are—and although the original design brief didn’t specifically say so, it was assumed they would be cheaper to buy. They are that, too. But only relative to new, standard-category airplanes and not compared to any of dozens of legacy two- and four-place airframes with similar or greater capability.

So, are LSAs cheaper to own than equivalent legacy airplanes? The answer depends on how you crunch the numbers, but if investment costs are tallied, the answer is no. If operating costs alone are considered, light sport airplanes look attractive against both legacy airplanes and definitely any new standard-category aircraft.

Compared To What?

Why do people buy light sport airplanes? Probably for exactly the purpose they were intended: Remaining in the flying game with modern airframes with modest performance. Although light sports haven’t been a runaway sales success, the total population of aircraft totals about 4000 airframes, according to www. bydanjohnson.com, which tracks production by models. And don’t look now, but sales of LSAs have recently accounted for between 19 and 21 percent of all piston aircraft sales, according to Johnson’s site and GAMA reports. (That includes ELSA kits, but not gyroplanes.)

In 2018 and 2019, the LSA segment registered 219 and 233 aircraft respectively, against total GA piston sales of 1137 and 1324 for the same years, according to GAMA. Those totals include 80-plus airframes from the five manufacturers who are GAMA members: Icon, Pipistrel, Tecnam, CubCrafters and Flight Design. The rest are from non-GAMA companies. Johnson warns because of fuzziness in the data, a precise market-share calculation is elusive. Still, LSAs have measurable presence.

As we’ve reported before, the LSA market is nothing if not lousy with variety. Dan Johnson’s site counts a dozen manufacturers delivering modest volume. Recent market leaders include Zenith, Kitfox, Van's, Rans, Pipistrel, Icon and Progressive Aerodyne. Flight Design once topped the market, but it’s now clawing back after financial retrenchment.

The typical price of a well-equipped LSA—and few buyers skimp on options—is north of $150,000. For our survey group of a dozen owners, the average price was $117,000, but some of the owners bought used airframes. The high price was $175,000.

At this juncture, you can slice the loaf two ways by asking what else $150,000 buys or what would an equivalent two-place airplane cost? This produces radically different outcomes. The 150 large would get you a nice late 1980s Mooney, a late 1990s Skylane or an early 2000s Skyhawk, for example. But it appears that buyers shopping LSAs don’t engage in that kind of calculus. They aren’t looking for price-value, exactly, as much as they are simple, easy-to-fly and easy-to-maintain airframes. Many of them are stepping down from more capable aircraft, including piston twins and even turbines. If cheap is the overarching driver in a two-place airplane, the pickings, while not necessarily slim, are vintage, not to put too delicate a point on it. Consider the last model year of the Cessna 152, 1986. Find them in the low- to mid-$40s to as much as $90,000 for a fully restored airframe. Piper’s two-place trainer, the Tomahawk, goes for a song and a parsimonious one at that: $14,000 to $20,000. The Beech Skipper is another possibility that’s a better flyer for around $16,000. And don’t forget the venerable forerunner of the 150, the 120/140 series. Again, prices for these are in the $25,000 to $35,000 range and some have been nicely restored. There’s also a passel of Pipers to pick from, including the J-3, the Super Cub, the Colt and even the Tri-Pacer if you want a backseat.

The immediate downside of these is most are standard-category airplanes and thus require the pilot to have a medical. While some thought BasicMed would decimate the light sport segment because pilots would have no worries about the medical issue, this is evidently not the case or at least is far less influential than we imagined. Several owners told us medical certification—or lack thereof—was a consideration in their purchase of an LSA and that BasicMed didn’t change that.

Cost Of Money

For our email survey of a dozen LSA owners, we asked about purchase price, insurance, fuel and hangarage costs and maintenance. But first, let’s dispense with the largish pachyderm on the premises: depreciation. This is always a slippery number, even for legacy airplanes and it’s all but impossible to calculate a meaningful average. For one, there aren’t enough sales of these airplanes to establish take-it-to-the-bank trends and for another, ultimate value is determined between the buyer and seller the moment the check is signed. But let’s do some for instances.

A CubCrafters Carbon Cub bought new in 2015 for $200,000 depreciated to $165,000 four years later or about 18 percent. Call it $9,000 per year. A Flight Design CTLS retailed for $156,500 in 2015 and now, according to Aircraft Bluebook, it’s typically worth about $115,000 for a depreciation of 27 percent or about $10,000 a year. For a longer timeline, consider Tecnam’s P92 Super Echo. It sold new in 2008 for $115,000 and now retails for about $45,000 for a loss of 61 percent value over 11 years or a decline of $6000 a year.

These exact values matter less than the fact that newer airframes will depreciate more than older ones will and it’s a real part of the cost of ownership. Older airplanes, say ragwings like Cubs and Champs or vintage Cessna 150/152s, will depreciate less or not at all. Some even appreciate slightly with market swings. Although many owners seem to purchase airplanes without financing, if a loan is required, the cost of that money should be added to depreciation.

Tallying It Up

Apart from purchase, depreciation and cost of money, the next largest expenses will be either fuel or insurance, according to our survey. That’s dependent on how much you fly, but the owners we surveyed averaged about 70 hours a year and reported an average of $19 an hour for fuel.

Using those numbers, fuel totals about $1330 a year. Much of the LSA fleet is powered by Rotax 912-series engines and although they’ll burn 100LL, they’re a lot happier on unleaded mogas. Many owners use that or, often, a mix. This may have a slight advantage in conferring better aging of the fuel, but even 50 hours a year on mogas is unlikely to cause varnish or deposit issues. Rotax recommends a shorter oil change interval when avgas is used: 25 hours if 100LL is used 50 percent of the time versus 100 hours if unleaded fuels are burned. Most owners stick to 50 hours or less for oil changes, whether flying with a Rotax engine or a legacy Lycoming or Continental.

Insurance is becoming a sticky point for owners and with the market hardening, it may be getting stickier yet. The average insurance cost among our dozen-owner survey was $1534. The highest was $3200 on a recent vintage Flight Design CTLS, the lowest $909 for an RV-12. Straight-up comparisons against legacy two-seaters are difficult because insurance on a Cub, a Champ or a Cessna 152 can cost just as much, depending on hull value.

The bigger driver may be pilot age. As the market hardens, more insurers are raising premiums on older pilots, if they’re not turning them down entirely. “Insurance has been $1100 a year. For the May 2020 renewal, it will be $1700 a year for a hull insured at $89,000. Time to lower the value,” said Flight Design owner John Horn. At these prices, more owners may be considering self-insuring the hull or entirely.

Operating Costs

If anything is a constant in aviation, it’s that’s bigger, faster airplanes burn through money at a faster rate and the near-ruinous annual is always in the offing. In that respect, legacy two-seaters and LSAs are definitely less money hungry, starting with annuals. Owners in our survey reported the average cost of an annual as $529. That requires amplification, however. Two of the owners in our survey group invested in a two-week course for the Light Sport Repairman Maintenance rating, which allows them to repair their own airplanes, including annual inspections.

While IAs can’t be fashioned in two weeks, we think this rating is a terrific idea. It costs up to $5000, but the real value is in engaging an owner in understanding the airplane, inspecting it for faults and repairing it when needed. In our view, that’s not just a cost benefit, but a safety enhancer, too. We asked owners if they had experienced any unusual maintenance issues, costs or problems that hadn’t been expected. None had, and all said the maintenance expenses were about what they expected or a little less. None had any complaints about the Rotax engines that power most of these aircraft. There were no reports of maintenance disasters such as corroded spars or major, timed-out parts.

What to compare the Rotax to? We can think of only three possibilities: the Continental A-65 found in Cubs and Champs, Lycoming’s O-235 or the Continental O-200, the lightened version of which is used in a few LSAs. The A-65 is on par with the Rotax for fuel burn, but the O-200 and O-235 are a tad thirstier. All three legacy engines are stone-age throwbacks compared to the Rotax, which has electronic ignition. The 912 iS also has fuel injection.

The Rotax is cheaper to overhaul. Dean Vogel at U.S. Rotax distributor Lockwood Aviation says the base overhaul price for a 912 ULS is $13,500, assuming a good core. A factory-new engine costs $19,000. The price delta between a new O-200 and an overhaul is larger and you can’t even get a new A-65, although new cylinders are available. The A-65 remains a serviceable choice, but overhauls are in the $15,000 to $18,000 range.

Vogel told us Lockwood advises owners of high-time or high-use aircraft to make the overhaul decision 500 or so hours before TBO. He said the engine can be sold on the used market to a homebuilder and the owner can then buy a factory-new engine, applying the considerable proceeds from the used engine sale.

Tying it Up

Owners who bought new or recent used light sport airplanes seem satisfied with the purchase and operating costs and report no unpleasant surprises, nor regrets in having made the purchase. These owners were a mix of step-down buyers and bucket listers who always wanted to own an airplane and found the ability to do that in an LSA.

“From my experience, LSA has become an accepted and somewhat vigorous part of U.S. general aviation,” said RV-12 owner Ian Heritch. “Wherever I go, I get only compliments and questions from onlookers. I have experienced no hostility for operating in the airspace system. While not the super-robust category that many were unwisely expecting, LSA has safely, smoothly and successfully joined the U.S. aviation family,” he adds. “If you want to keep flying, this is the way to go,” adds CTLS owner Ben Short.

But the design brief is to determine whether an LSA is cheaper to own and operate. It can be, if it’s bought right. If you don’t factor in the steep depreciation a new aircraft suffers the day after you take delivery, then new and used are comparable. “Bought right” to us means an airframe that’s had the painful part of the depreciation already squeezed out of it. That means at least five years old, but 10 would be better.

There are bargains out there. A 2006 Flight Design CTSW is still perfectly serviceable and supported with a typical values in the mid-50s. Newer ones with glass panels aren’t much more. Even at the higher purchase price, ownership costs would be competitive with a legacy two-seater. If you can’t find or afford a hangar, a glass airplane can live outside or in a shade hangar, which a ragwing— vintage or newer—cannot.

Speaking of ragwings, the Cubstyle airplanes appear to hold value better than other LSAs. Specifically, a five-year-old Carbon Cub still commands $165,000, according to Bluebook. Arch competitor Legend shows similar price stability, making them a good choice if short-term ownership is envisioned. You can get in and out without losing much.

That’s true of all of the legacy models that qualify for LSA operation, too. They’ve reached rock-bottom value and aren’t likely to depreciate much at all, if that’s a buying consideration. Some parts for older aircraft are hard to come by, but owners tell us they remain supportable. Just make sure the pre-buy filters out expensive gotchas.

The Cost Of A Cub

A vintage Piper J-3 is a popular choice for light sport flying and having owned and managed the partnership in one for the past 10 years, I understand why. With no electrical system and stone-age construction, there’s simply not much to go wrong in the airplane and maintenance between annuals has been all but nil. But while a more capable airplane can take your leg off at the knee when some unexpected expense surfaces—like an engine—the Cub tends to take little nibbles. For example, the old-style 800-4 tires cost $330 each and another $200 for the tubes. And we had to do the engine six years ago after a cylinder went soft and a rod got wobbly on the crankshaft. At that time, Don’s Dream Machines overhauled the A-65 for $12,500. Now they’re quoting $15,000 to $18,000.

Annuals aren’t agita producing, typically totaling around $800 to $1000. But we’ve had a few that amounted to twice that when airframe repairs, exhaust work or other maintenance came due.

Insurance has been as little as $900 and as much as $1300, for three experienced but older pilots and based on a hull value of $36,000. In keeping with market trends, I expect a little higher next year.

When I total up my share of expenses in the partnership, $2500 a year covers it—generously. I flew the airplane seven hours last year, which appalled me when the shop informed me of it. I’m on track to fly 50 this year, which makes it worth owning. As most Cub owners will tell you, flying consists of local flights and pattern work. My major cross country is Arcadia, Florida, 36 miles east. It has a nice grass runway as does little Buchan field, seven miles south of Venice.

These numbers are lower than a new Legend or even a used CubCrafters model. Lower hull value is one factor, but so are radios and an electrical system. They add to repair costs. Those airplanes burn a little more fuel than the A-65, but maybe dozens of gallons more over the course of year.

The newer Cubs are considerably more capable. They’re faster and more comfortable, making even longish trips practical if there’s no time pressure. In a J-3, such a thing can be an ordeal, not least of which because the old Cubs don’t fly as well as the newer versions, which are based on Super Cub airframes.

I am saving the next item for last, because like many ragwing owners, I’m suppressing thinking about having to actually do it: Re-covering the airplane. Anyone buying a rag-and-tube airplane should be aware of where the airplane is in its cover cycle. Better budget $30,000 to do this, to allow for repairs to the tube work if it hasn’t seen the light of day in 30 years. And that’s how long a cover might last, if everything goes just right and the airplane is hangared in a dry climate. Outside? Forget it. If you’re even thinking about that, you don’t understand.

The cost of re-covering can easily exceed the value of the airplane, especially for a Champ, and it will render an otherwise desirable airframe a non-starter unless the price is reduced to allow for the cover work. If you’re considering a Cub or a Champ, check the logs carefully for the date of the last cover and have it examined by someone who knows the craft. That might require flying them to the airplane since qualified fabric techs aren’t always available where you might need them.

This article originally appeared in the June 2020 issue of Aviation Consumer magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to Aviation Consumer!