Henry Haigh

Creativity may come from thinking outside the box, but if you fly outside the box in competitive aerobatics, you’re history. Henry Haigh flew inside the box well enough to win the World Aerobatic Championship in 1988, at age 64. Fresh from last month’s induction into the IAC Hall of Fame, Henry talks with AVweb’s Joe Godfrey about representing the U.S., the airplanes he built and flew, and his twenty years of competitive yanking and banking.

Henry Haigh was born in 1924 inAnn Arbor, Mich. It wasn't long before he was flying aerobatic competitionsusing gas-powered RCs. Uncle Sam taught him how to fly real airplanes, but WWIIended before Henry could get into it. After some time off to raise his familyand start a business, Henry bought a Ryan PT-22 and resumed flying, and begancompetitive aerobatics in the early '60s, winning his first contest. He won the IACcompetition at Fond Du Lac a total of seven times, placed second in the UnitedStates championship several times, and won the United States AerobaticChampionship in 1980.

Henry Haigh was born in 1924 inAnn Arbor, Mich. It wasn't long before he was flying aerobatic competitionsusing gas-powered RCs. Uncle Sam taught him how to fly real airplanes, but WWIIended before Henry could get into it. After some time off to raise his familyand start a business, Henry bought a Ryan PT-22 and resumed flying, and begancompetitive aerobatics in the early '60s, winning his first contest. He won the IACcompetition at Fond Du Lac a total of seven times, placed second in the UnitedStates championship several times, and won the United States AerobaticChampionship in 1980.

He was on the U.S. team every year from 1973-1991. In 1976, Henry placedfirst on the U.S. team, but with USA-USSR tension building, the proverbialRussian judge bumped him to 13th overall. He kept practicing, changed airplanes,modified his routine, always looking for improvement. In 1988, at the age of 64,the dedication and practice paid off when he won the World AerobaticChampionship, beating second-place finisher Kermit Weeks. AVweb'sHoward Fried says Henry is "the smoothest and most precise manipulatorI have been privileged to observe in a lifetime of attending airshows andaerobatic competitions." These days, retired from competition, Henry livesin Howell, Mich., and flies a Super Cub, a C-185 on floats and is building amodified Super Cub. He was inducted into the IACHall of Fame in October, 1999.

What do you remember about learning how to fly?

When I was a kid I just took to airplanes. Every toy I ever cared about was amodel airplane or something that flew. I got into gas-powered model airplanes inhigh school and entered some contests. Just as I was getting into that I joinedthe cadet program of the Air Force. I graduated from the cadet program in 1944and went to B-24 school in Kirtland, Alabama. I finished B-24 school on VE day,the day the war ended in Europe. That stopped all training of B-24s, there wasno point in doing any more. So I was sent to B-29 school and was sent to Kearns,Utah, which is an overseas replacement depot. While we were training there andwaiting to get a whole squadron together to go to Saipan for an attack on Japan,they dropped the atom bomb and that ended all the training. So I'm lucky that Igot a lot of very expensive excellent training and never had to shoot anybody orget shot at.

I got an education, too. Prior to my entering the cadet program they had arequirement and were only taking people with two years of college or better.They ran out of those guys about six months before I joined up. So they put outthe word that if you volunteered for induction you could get into the Air Forceand they would send you to a college training detachment. That's how I got inand I was sent to the University of Tennessee where I got a year's credit.

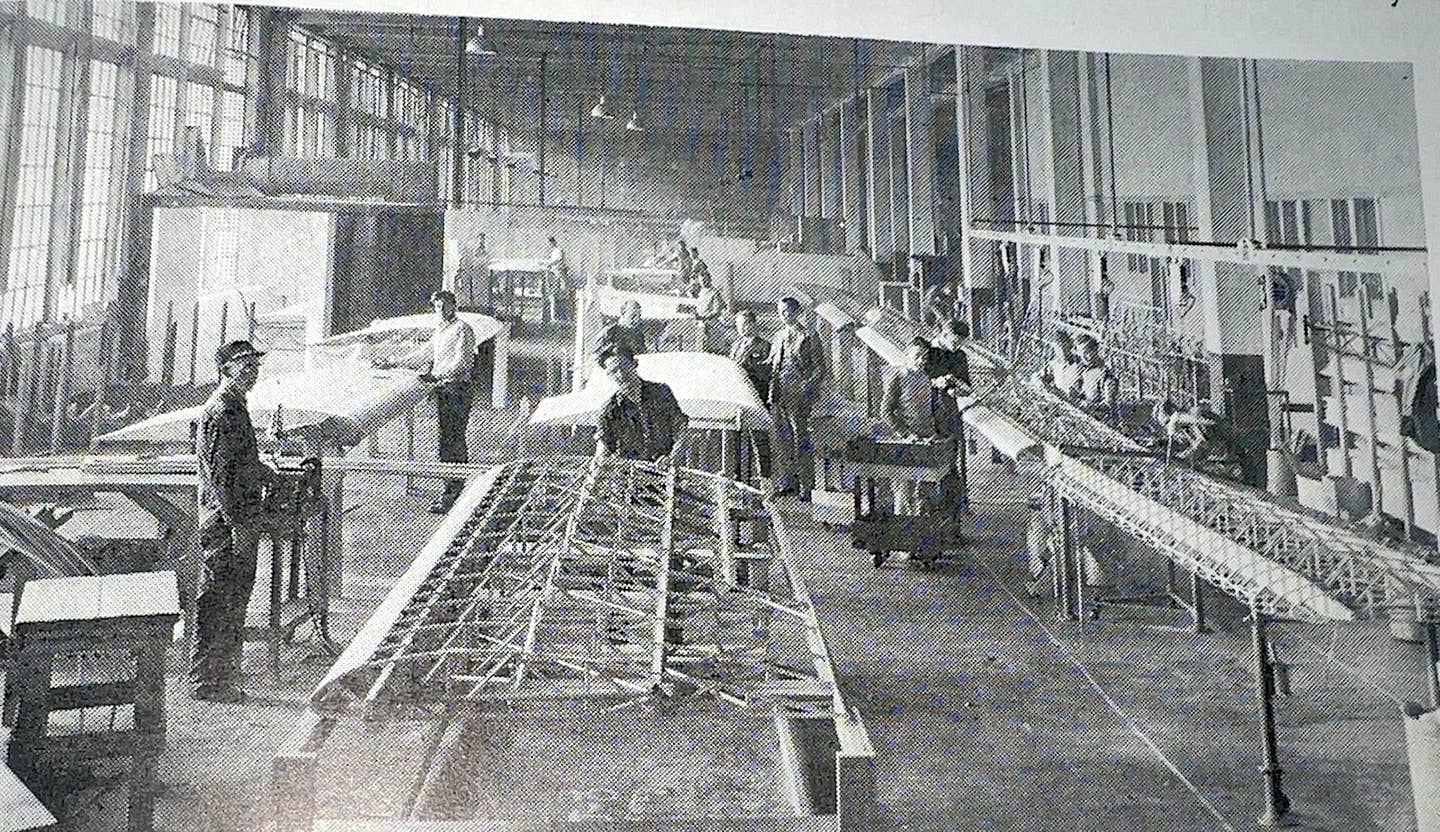

After the military I went to Wayne University to finish my education. Myfather had started a small machine shop during the war making B-24 parts, whichis ironic. When the war ended he started making parts for Ford and GM and that'swhere I worked part-time when I went to college.

There's a Henry Haigh high school in Dearborn. Who is that named for?

That's my grandfather. He was one of the pioneers in Dearborn. He was alawyer and a friend of Henry Ford. When he retired from law he did some writingfor the Henry Ford Museum. That's about all I remember about him.

When did you get interested in aerobatic competition?

I put flying on the back burner after the military. I was concentrating oncollege and I got married and had the responsibilities of a family so I didn'treally touch an airplane for about 10 years after I got out of the Air Force.One of my loves was aerobatics so when I did get back to flying that's what Istarted doing. I had a traveling airplane, a Cessna 172, and I'd fly to seecustomers with that. But for aerobatics, I bought an old Ryan PT-22, which is aterrible aerobatic airplane. It would go upside down and it would do a loop butthe only thing it did really well was snap rolls. It did beautiful snap rolls.

I was slowly leaning toward competition and I got to know some of the peopledoing it. I flew the Ryan for a few years then I had a Zlin, then a Bcker andalong the way I met Curtis Pitts. He sold me a nice round-wing Pitts and Istarted competing in about 1970, and I was able to compete for about 20 years.

When did you enter international competition?

|

I had always had a goal of being on the United States Aerobatic Team that wentagainst the best pilots from around the world. I qualified for that team in '73and I was a member of the team every year from '73 until '91. In order to dothat you have to finish 5th or better in the U.S. National Championships. I dida six or seven regional competitions a year in the states to practice for theinternationals. I finished first on the U.S. team when we went to Russia in '76,but I finished 13th overall. I took a beating from the Russian judge.

I finished second in the 1980 world championship in Oshkosh. I kept trainingand working on getting better and I went to Spitzerburg, Austria in 1982 andmissed winning the world championship by 5 points out of 17,900. It was close. Iwon the world championship in Red Deer, Alberta in 1988, at the age of 64. I'min the Guinness Book of Records as the oldest pilot ever to win the worldchampionship.

I'd like the politicians to explain if an airline pilot isn't qualified tofly at age 60, how could I come along at 64 and beat 80 of the world's bestpilots? I think it ought to be up to the individual's physical condition. Theyshould set some high standards but if a pilot gets to be 60 and he's physicallycapable and his heart's in good shape I don't know why he shouldn't be allowedto keep on flying for a while. There are quite a few airline pilots in aerobaticcompetition. I got to know them and compete against them and they hit 60 andthey can still fly competitions but they get kicked out of the airline. Here's aguy who can push and pull 9 Gs for 20 minutes at a time and he does it four orfive times a day and he's in great shape.

I couldn't say what the arbitrary cutoff date ought to be but there arecertainly a lot of guys out there flying that ought to be allowed to go on ifthey want to and they can meet the physical criteria for it.

Who were your teammates on the U.S. teams?

There were so many talented pilots. Many of them were airline pilots and manyweren't. They were all extremely talented. I'd hate to start naming namesbecause I'd hate to leave somebody out. Everybody that made it to the team wasdedicated and capable.

Tell us about the international competition itself and how you preparedfor it.

The program when I was flying was to fly three separate flights in front ofjudges. One of the flights was a known compulsory that was published at thebeginning of each year. The international teams would have input and they'ddevelop a routine of about 20 maneuvers over twelve minutes or so. Everybody inthe whole world flies the same routine. You find out about it early in thespring and you can practice it all summer long. Then there's a freestyle flightthat has has to include so many maneuvers from each family and it's about thesame length. That one you can design yourself. The last flight is an unknownthat nobody gets to see until the day before so you don't get a chance topractice it. When it gets handed out you take it back to your room and study itand try to memorize it. The way to prepare for that is to practice all themaneuvers that you know will be on the unknown. It's about the same length asthe other two flights.

Just going out and practicing one maneuver over and over doesn't give you theproper workout because you can set up the entry speed any way you want to. Theway to practice a difficult maneuver is to put a couple of maneuvers ahead of itso you force yourself to think ahead and set up the proper speed and the correctposition coming into it.

|

at Yverdon, Switzerland, 1990 |

I practiced around home every day, with at least one 25- or 20-minute flight.That doesn't sound like a lot but when you practice the 100-yard dash you don'tpractice it for an hour. I'd go out and fly two routines of about 10 minuteseach, then spend another few minutes on individual maneuvers. That would give meabout a half-hour of flying and I'd be wringing wet and there'd be perspirationon the canopy and I'd put the airplane away and come back and do the same thingthe next day.

For a big contest like the U.S. Nationals or Fond du Lac I'd go off for aweek with my friends, the other competitors. One of us would fly and the otherswould critique us on the radio. I'd be helping my competitors just like they'dbe helping me. In five or six days of that you could log about 14 hours on thetach. That isn't a lot of cross-country time but that's a lot of practice.

How much did you modify your freestyle from year to year?

I kept trying to make it easier for myself. The freestyle used to be 30maneuvers. But when you've got eighty pilots in world competition and it takestwo days to fly the whole group it's killing the judges. They're standing outthere 10 hours a day in the hot sun. So they cut the freestyle from 30 maneuversto 20, but they left the difficulty coefficient the same, so you had to compoundmore maneuvers. You couldn't just pull up and do a hammerhead, you had to do aroll coming up and a four-point roll coming down, or some other compoundmaneuver to keep the difficulty coefficient up. So every year I'd look for a wayto build a routine that I could fly and get points.

|

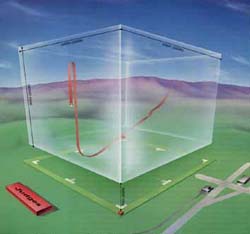

| Aerobatic box graphic courtesy of Air & Space Magazine |

How big is the competitionbox?

The box is 1,000 meters square with white panels on the ground that are bigenough to be seen from 3,000 feet. The boundary judges are 50 meters outsidethat box with sighting devices and radios and if you go outside that box you'redead. You have no chance of winning an international title if you go outside thebox.

So it's important to have the airplane exactly where you want it for everymaneuver, and while you're in the middle of that maneuver you're thinking two orthree maneuvers ahead. This is all happening very fast and there's a lot ofphysical strain. To do the routine properly you're looking at nine Gs positiveand negative every time I'd fly. You develop some tolerance for the Gs by a lotof practice. If you just started at nine you'd pass out. You have to work up toit. Here in Michigan I couldn't fly much in the wintertime so when I'd startflying again in the spring it would take me two weeks to get acclimated topulling and pushing Gs again.

Did you ever turn the wrong way or skip a maneuver?

Oh sure. Everybody does that when they're starting out. You've got your cardthere on the instrument panel and it's very easy to skip a line and leavesomething out, or turn the wrong way. And you've got places where you cansubstitute one maneuver for another. It's very easy, for instance, to substitutea half-Cuban for a horizontal 8. The first part of a horizontal eight starts outas a half-Cuban. You might pull up into a horizontal 8 and do the half rollcoming down and now you're in the Cuban 8 and you've got a Cuban 8 you'resupposed to do later and now you're lost. That can happen when you're startingout then as you get more comfortable you take steps to make sure it doesn't.

Did you fly the competitions in the Haigh Special?

|

The Haigh Special is one of the last airplanes I built. I sold that to ChrisPanzl. It's a highly modified Pitts. The top wing was swept, the fuselagewas longer, much bigger engine, retractable landing gear, and it was quite aperformer, but I never competed with it. I competed with two airplanes, one Icalled a Super Pitts. It was the first Pitts to compete with spring aluminumgear, it was a very clean airplane, very light, and had 15-20% better verticalpenetration that a stock Pitts. I flew that airplane until 1978 when I switchedto a monoplane that I called a Superstar. I switched to the monoplane becausethe Europeans kind of looked down on the biplanes. I will admit that the Pittsis so small and boxy that it's difficult to judge it. The biplanes outperformedanything out there, and still do, but when the Europeans went to the monoplanesit was hard to score well with a biplane. That's why I switched.

The Superstar is a standard mid-wing airplane with a 200-horsepower engine.It had very good vertical penetration but you had to fly it very fast. Themonoplanes were hard to recover from if you happened to get low and slow on anunknown routine, for instance. The biplanes were so light and agile that youcould get the speed back, but you really had to control the monoplanes. I wonthe world championship in 1988 and finished second in the world in 1992 in theSuperstar.

Can we ever get the politics out of international competition?

In 1976 the Russians made a political contest out of what should have been anaerobatic contest. Their press releases announced that their Russian pilots weredoing so well, and they played a lot of games with us. It was the first worldcontest I had ever flown in. There had been no world contest in 1974 for somereason so it had been four years since the last competition and we reallycouldn't get much feedback from the previous U. S. team pilots. So we werelearning from the beginning and the Russians had some fun with us, changing therules in the middle of the game and pulling little funny tricks. It was a goodlearning experience for us.

In all those Gs did you ever have a structural failure or an enginefailure?

Everybody has an engine quit on them once in a while I guess. I readsomewhere that your chances of having a complete engine failure are about thesame as your chances of winning the Irish Sweepstakes. So I flew for years andyears and never had any trouble and then I won the Irish Sweepstakes two timesin one year. I had a Bonanza with a brand new engine that threw a rod anddisintegrated the engine. Fortunately I was coming into the Pontiac airport whenit happened and I was able to make it in. I've had little problems now and thenthat everybody has, but I think the military training that I had taught me tohandle the emergency and stay cool. No matter what you've got to keep flying theairplane.

I like that old saying: Let me use my superior judgment to keep from havingto use my superior flying skills to stay out of trouble.

Both of your sons fly. Did you teach them?

There's a problem when you start teaching your family. When you tell somebodythey did something wrong or made a mistake it changes from instruction tocriticism. It's very difficult to overpower that. My oldest boy was living inTennessee and got to know the airport manager there and that's where he learnedto fly. I did give a lesson or two to my younger son and I could see right awaythat no matter how careful I was with my words and no matter what I dideverything came off as criticism. There was a heck of a good instructor nearbyand I liked his system. He gave all of his students their first 15 or so hoursin a J-3 Cub, then switched them to a 150 for the radios and instrument work. Somy son Matthew got real good training and now he's a heck of a good pilot.

What is that instructor's name?

Joe Grastik is his name. He's no longer living. He was a commercial painterand taught flying in the evenings and on weekends and put a lot of studentsthrough his school.

What products does Haigh Aviation make?

My son started a company a while back to make machine parts. We manufactureda tailwheel for the Pitts. It can be a difficult airplane to land. When I wasflying I was always fooling around changing things, trying to improve them, andone of the first things I made was a lockable tailwheel for the Pitts. That madeit a dream to land and I guess we've sold about 3,000 of them. The company rightnow is making automotive parts with computerized milling machines and now doinganything aviation-related right now.

In the AOPA airport directory there's a note for the Howell, Michiganairport that says "intensive flight training." Is that you?

I wouldn't call it intensive. We have two schools on the field and they dopretty well. The airport has had some problems, like a lot of small, localairports out in the country. But it's starting to get developed now, and they'reputting in an instrument runway and making other improvements. I don't teach.

What airplane are you flying now?

I have a Super Cub and a 185 on floats and I'm building an airplane that'llbe a modified Super Cub. I don't fly aerobatics anymore. I've been there donethat. I spend time fishing and take the floatplane up to Canada.