Smokin’: Buying 200 Knots For $200,000

Insert your favorite speed cliché here. One of the main reasons we love airplanes is that they go fast—and the faster the better. We post photos on social media of…

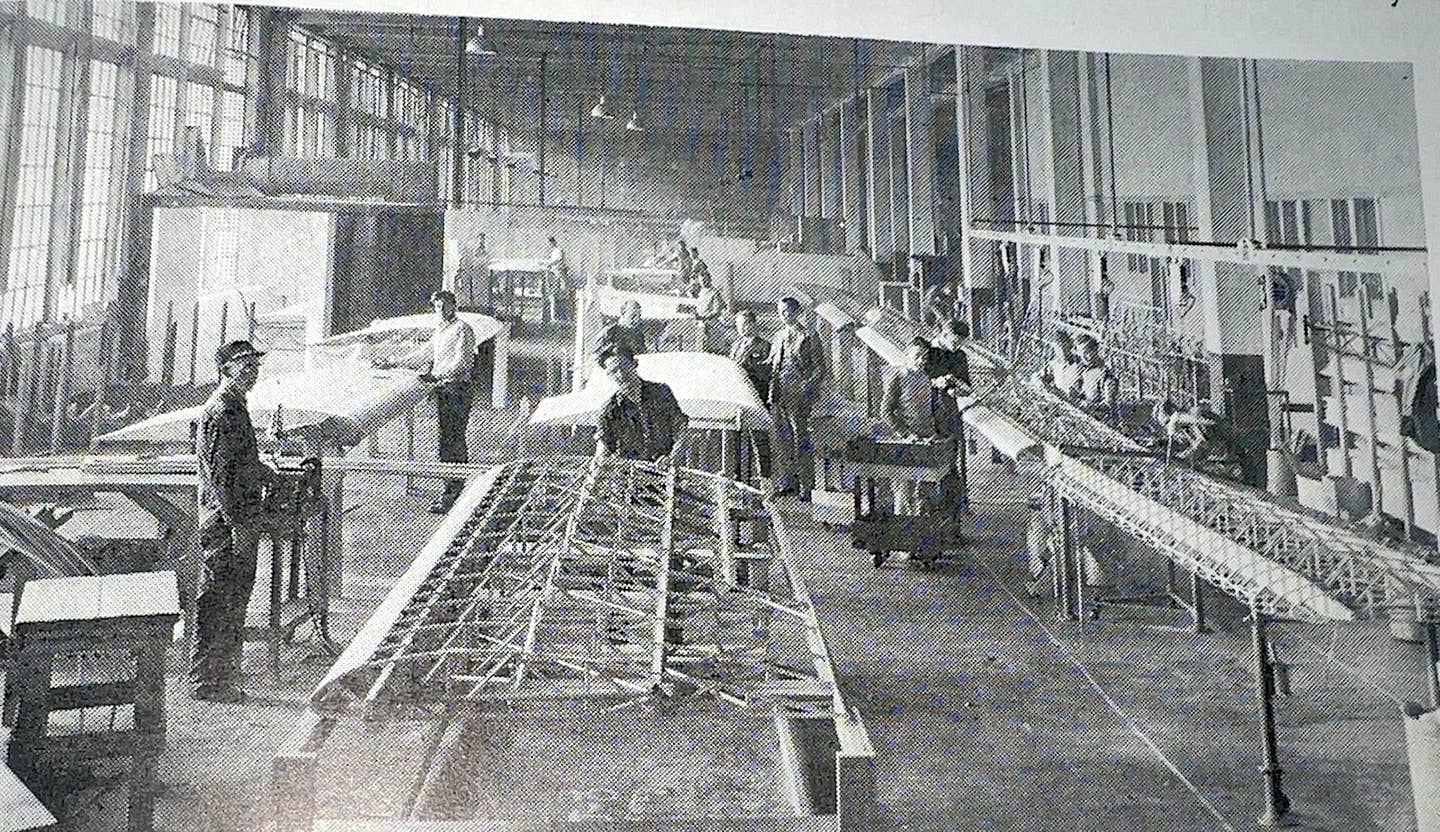

The Mooney M20M Bravo will cook along at over 220 knots in cruise.

Insert your favorite speed cliché here. One of the main reasons we love airplanes is that they go fast—and the faster the better. We post photos on social media of the GPS when riding a screaming tailwind and we agonize over the numbers when imprisoned in a headwind. And no matter what we’re flying, we’ve been heard to say, “It’s a great airplane. I just wish it were a little faster.”

Over the years, the number that keeps coming up when we talk to pilots about the speed they’d really like to have is 200 knots TAS. That’s smoking right along. It means potentially having to pay attention to the 250-knot IAS speed limit below 10,000 feet when in a descent and definitely be ready for the 200-knot IAS speed limit under Class B airspace and in certain parts of Class C and D airspace. “That’s cool, man. My airplane is so fast that there are times I’ve got to slow down so I don’t get busted.”

Rational?

Yes, we know that rational voices tell us that head-to-head on a 200 NM trip on a calm day, the 200- knot speedster will be just shutting down on the ramp as a 180-knot machine is entering the pattern. It can’t be worth the extra money to buy 200 knots.

To start with, we’re not talking being rational, we’re talking speed and pilots are not known for being rational about speed. We load the heavy stuff in the back end of the baggage compartment to move the CG farther aft for a little more speed. It’s why aircraft manufacturers publish cruise performance at the worst possible power setting for engine longevity—50 degrees rich of peak EGT—because it gives the highest numbers.

And, if we are being rational, extra cruise speed starts to really make a difference when dealing with a headwind. As TAS goes up, the percentage of it affected by a headwind drops. Trying to go 1,000 NM into a 30-knot headwind? The 200-knot bird will need about 5:50. The 180-knot machine will take nearly another hour.

But who is going on a 1000 NM trip with any regularity? Worrying about the stuff we don’t often do is what we get when we try to be rational about speed. Speed is valuable for its existence; its existence makes us want it. And want it we do.

But speed means overcoming drag and that means power, lots more power. That costs money, so we buy the speed we can afford. And, therein lie the questions. What can we afford? How much does speed cost?

So to square the power setting for 200 knots, so to speak, we asked whether it’s possible to buy 200 knots for $200,000.

It is. But, as we quickly learned, rarely with single-engine machines, but not at all difficult when looking at twins. And it’s all about cost of operation. An attractive purchase price can suck a buyer who isn’t cautious into operating costs of $500 per hour—and that’s if the airplane is in good shape.

Cheap Twins

We found a lot of turbocharged twins that hustle along at or above 200 knots for less than $200,000. We’re going to emphasize how expensive they can be to operate because the low purchase price and smoking cruise speeds have put stars in a lot of buyers’ eyes. Our rule of thumb is that a twin costs at least three times as much to operate as a single of comparable speed. That includes everything from higher insurance rates (if you can get insurance in the current hard market), system complexity, insurance recurrent training requirements and little, frustrating things such as getting charged much more for parking than a single that is the same size and possibly not fitting in a T-hangar.

Plus, with redundant engines, there are that many more things to break.

Nevertheless, we like twins a lot—especially when we spent a lot of time flying at night over the Great Lakes. We think that if we had $300,000 to spend on a 2006 Mooney Acclaim that we’d much rather plunk down $150,000 on a 1981 Aerostar 601P and use the other $150,000 to operate it while enjoying a comfortable, pressurized cabin whistling along at over 220 knots with the good feeling that there are two engines out there snoring along in the night over terrain or water we don’t want to visit.

A Million Bucks

As we looked at what we could buy for $200,000 and cruised at more than 200 knots we kept a few things in mind. If any of the airplanes were new, they’d cost at least $1 million, so we aren’t maintaining a $200,000 airplane, we’re maintaining a million-dollar bird. Plus, buying that speed means buying turbocharging (two per engine on the Aerostar 601P) and dealing with the extra maintenance costs created by handling the heat they generate—read expensive and essential exhaust system inspections and component replacements—and knowing that they will probably have to be overhauled or replaced after 1000 hours in service.

Owners of over-200-knot twins consistently told us that you have to find an A&P who is an expert on the particular type of airplane and you have to become an expert on it as well. Ignorance is expensive.

They also warned us to watch out for turbocharged twins bought by “cheapskate airline pilots or doctors” who neglect the airplanes to the point that when they go on the market they need total restoration. We were given the example of a 601P Aerostar that sold for $200,000 to a cheapskate and when he’d finished neglecting it, it was in such bad shape that all he could get for it was $80,000.

We’ve advocated joint ownership of aircraft to allow a pilot to get more airplane than possible when buying one as an individual. In the world of 200-knot-plus flying machines joint ownership may be difficult, primarily because it can be tough finding others who have the chops to fly the airplanes involved or meet insurance requirements.

With that as background, here’s what we found will give 200 knots for $200,000.

Aerostar

Rightfully known as the fastest piston twins, designer Ted Smith’s line of aluminum bullets will all cruise north of 200 knots. Ownership of the line changed hands numerous times—we won’t even try to trace the iterations here. Suffice to say that these are sophisticated machines that require sophisticated checkouts and recurrent training because of their speed and not always intuitive systems. More than one “Just lead me to it, I can fly anything” pilot has come to grief in these fast movers.

For an owner willing to do the homework necessary to find a good one—we recommend starting with the excellent Aerostar Owner’s Association (www.aerostar-owners.com)—the reward can be comfortable, capable high-speed travel, although pushing the speed up above 240 KTAS means fuel burns in the 40 GPH range. However, because the airplanes are so slick, pulling the power back doesn’t mean slogging through the sky. On an evaluation flight of a 601P, we noted 205 KTAS while burning 25 GPH operating LOP and 242 KTAS when shoveling 44 GPH through the mills.

Bluebook indicated prices as low as $60,000 for an early 600, $150,000 for a 1981 601P and $185,000 for a 1983 602P.

Mooney

Once Mooney began dropping big, turbocharged engines in their tightly wrapped speedsters, the line was always at the top or nearby when it came to fastest production piston single. By 1986 the 231 had been tweaked enough that it just crossed into 200-knot territory, doing so on 11.5 GPH at FL210, although we consider the 252 a more realistic 200-knot machine. The Bluebook shows the 1988 252 TSE changing hands for $139,000, 231s a bit less.

Other Mooneys meeting our criteria were the 1989 M20M TLS at $110,000 and the 2000 M20M Bravo at $195,000.

The 1960s-vintage pressurized Mooney M22 Mustang will cruise at 200 KTAS. Maintenance issues and lack of parts put it into the not realistic column even though you might find one for under $40,000.

Cessna

The turbocharged Cessna singles either didn’t make the 200-knot cut (210 through the N model) or couldn’t be bought for under $200,000 (210R and Columbia 400/Cessna TTX).

More realistic are the turbocharged and pressurized Cessna twins. Cessna pioneered general aviation turbocharging with the 1962 Model 320 Skyknight. It was not a turbocharged 310—there are significant differences and they have separate type certificates. It’s fast, but owner feedback is that maintenance issues on that first-generation turbocharging are enough that we don’t recommend a purchase.

The T310 series are capable of cruising at 220 knots in the flight levels. Bluebook showed $110,000 for a 1974 T310Q and $148,000 for a 1981 T310R. As with all of the Cessna turbocharged twins, careful exhaust system maintenance is essential.

The 340 can be referred to with some accuracy as a pressurized T310. Cruise speeds are comparable and handling is nearly identical but the airplanes suffered from a poor useful load when full of fuel—and it could carry a lot of fuel.

The gross weight increase allowed by the aftermarket VG mod turned the airplane into a decent load hauler and improved low-speed handling. Bluebook indicates prices of $110,000 for a 1972 340 and $200,000 for a 1980 340A.

The Model 335 was intended to be an unpressurized 340, but that didn’t shed the weight and had less power. You can buy one for $130,000. Our recommendation? You can find a better airplane for the money.

400 Series

Cessna began its 400-series twins— characterized by wider, oval-shaped cabins and luxury car handling—with the Model 411 in 1965. The 411 and 411A are extremely expensive to maintain and prices reflect the fact: $37,000 for a 1965 411 and $40,000 for a 1968 411A. Don’t let the price of admission fool you; you can go broke in happier circumstances than trying to keep a 411 running.

401/402

The 401 and 402 were virtually identical airplanes, with the 401 intended to be an executive transport and the 402 a freighter or small commuter airliner. They will cruise above 200 knots in the flight levels; however, they are better known as load haulers.

All but the newest can be had for under $200,000 with a 1967 401/402 priced at $55,000 and a 1982 402C at $195,000. Proceed cautiously; many were used hard as freighters.

The 414 has similar engines to the 340, but a bigger cabin—so it’s slightly slower. It will cruise at 205 knots at 38 GPH in the flight levels. We saw Bluebook prices of $105,000 for a 1970 model and $160,000 for a 1978 414A.

The Cessna 421 uses the geared GTSIO-520 engine that initially suffered from a reputation for short life and consequent high maintenance costs. The advent of the digital engine monitor made a big difference in engine life expectancy, and made ownership costs of the airplane less eye-watering.

Turboprop Speed

At altitude, the 421 will scoot along at over 230 knots, faster than some turboprops. Owners tell us that even with engine overhauls running north of $50,000, they would rather have their 421s than a turboprop.

Bluebook shows a 1968 421 at $95,000 and the most recent model that falls in our price range, the 1976 421C, at $195,000.

There are more mods for twin Cessnas than we can conveniently count. If we were to point to one that we recommend, it’s VGs as they generally lower stall speed, reduce VMC and increase useful load.

Beechcraft

From the original 185-HP Bonanza the speed-amenable airframe responded to power upgrades in ways that meant there were rarely buyer shortages. A few of the turbocharged models—and, through aftermarket turbonormalizing by Tornado Alley Turbo—will cruise faster than 200 knots. We recommend the aftermarket, more sophisticated, turbonormalizing mod over factory turbocharging.

We think that the 1966 through 1970 V35TC airplanes meet the 200-knot threshold at pretty attractive prices: $65,000 for the 1966 model and $70,000 for a 1970 machine.

We also think that a person can pick up a used 1974 V35B Bonanza for $100,000, install Tornado Alley’s turbonormalizing mod for $50,000 and add tip tank and gross weight increase mods and come away with an airplane that will carry 600 pounds in the cabin and fly 1000 NM at 200 knots with VFR reserves without spending $200,000.

Baron

Most of the airplanes in the turbocharged Baron line will cross the 200-knot cruise threshold, although as with many of the Cessna twins, only slightly and at high power settings and fuel flows.

Of the short-body Barons, the big-engine C55, D55 and E55 made our cut with prices ranging from a 1966 C55 at $75,000 through a 1968 D55 at $78,000 to a 1982 E55 at $170,000.

The turbocharged long-body Barons as well as the pressurized Baron break 200 knots at altitude without breathing hard. While purchase price won’t break the bank, maintenance can, so shop carefully.

The Bluebook showed us $70,000 for a 1967 56TC, $125,000 for a 1976 58TC and $185,000 for a 1980 P Baron.

One of the most attractive airplanes to ever launch off of a runway is the Beech Duke. Cruising at 220 knots in pressurized luxury at FL240, plan on running a minimum of 40 GPH through the very-expensive-to-overhaul 390-HP Lycoming TIO-541 powerplants.

Users tell of us of impressive love-hate relationships. We’ve watched buyers eagerly plunk down the money to buy one only to unload it within months, while others have had theirs for decades. Bluebook reported a price of $195,000 for a 1982 B-60.

Piper

Piper’s line of pressurized singles evolving from the original Malibu will all cruise at or above 200 KTAS at altitude. What they will not do is change hands for under $200,000— they hold their value.

That moves us to some of the Navajos as the 200-knot Pipers (yes, we know Piper owned the Aerostar line for a while, but was only one of the owners).

We’ll say it bluntly: The Navajo model line is confusing. The PA-31 was produced in a half-dozen variants spanning two fuselage sizes over a 17-year production run beginning in 1967 and ending in 1984. All told, just over 1500 were built, the lion’s share of them the long-fuselage Chieftain version. Virtually all were turbocharged and some of them had enough power to hit 200 knots in cruise in the high teens.

We like them for their large, comfortable cabins and pleasant handling, but not for their reputation for a compulsion to visit the shop frequently and the stack of ADs against the marque. We saw Bluebook prices for the pressurized Navajo at $95,000 for the 1970 model and $150,000 for a 1977 bird.

Bottom line—we think of them as we do the Cessna 401/402—haulers, not speedsters.

Conclusion

Our research confirmed our hypothesis regarding admission to the 200-knot club: You’ve got to shell out significant bucks and that’s either going to be on the initial purchase price of a single or the care and feeding of a twin.

From our point of view, an over-200-knot piston-engine airplane approaches being the perfect personal hot rod. With the speed, handling and weather capability, we’d opt for a pressurized twin such as an Aerostar 601P, P Baron, Cessna 340A, 414A or 421C, recognizing that the cost of maintaining them is going to be something else again—and finding a good one is going to take some hard, careful looking.

From an economics standpoint, we’d go with a turbonormalized Beech V35 Bonanza with tip tanks.

We’d only view a Mooney Mustang, Cessna 411 or 335 from a distance, a long distance.

200-Knot Buzzkill: MX, Insurance Realities

We don’t have to remind anyone that there aren’t any free lunches in the 200-knot club, do we? To go fast there’s always stuff to spend money on, and first and foremost is training, aggressive maintenance and upgrades, while insurance eligibility hangs in the balance. Put simply, if your flying credentials look questionable on paper, the chances of an insurer taking on the risk of you at the controls of an Aerostar, pressurized Baron or Cessna 414 aren’t favorable. Get a quote before doing anything else.

But for the skillful and financially qualified owner/pilot, let’s take a look at the current market to see what that 200 knots could really cost. We’re realists (and trained pessimists) and always plan for a worst-case scenario during the first year of ownership. That means having to swap an engine or two, dealing with avionics repairs and upgrades and generally getting to know what the new-to-us airplane is made of.

In the winter of 2020, we landed at Controller.com, the respected aircraft virtual marketplace, and went shopping for an Aerostar. The first hit turned up a 1975 601P/Superstar 700, for sale in Louisiana. The Superstar performance specs claim 261 knots at 75 percent power, and a blistering 285 knots at full throttle, plus a 230 FPM single-engine climb. It has spoilers, full de-ice and plenty of speed mods. The current Aircraft Bluebook suggests an average retail price of $100,000, and to add $156,225 if it has the Superstar conversion with new engines. This was priced at $160,000 with old ones.

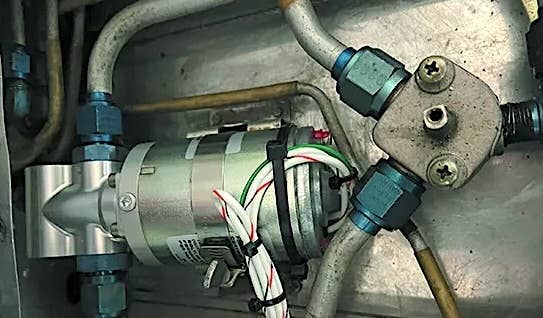

The Lycoming IO-540-S1A5-series engines (and Hartzell props) are at 1400 hours into the 1800-hour published TBO. If either—or both— of them tank, the average nut to crack for an overhaul is realistically $50,000 each. For those keeping a tally, we just bought a $260,000 twin. But at least it has fresh engines and props. After the first couple of trips in atrocious weather, we might miss flying with the Garmin glass we had in our old airplane because this has a Bendix mechanical HSI and traditional round-gauge flight instruments. Thoughts now turn to some avionics improvements, and that logically includes transitioning it to glass. One option is Garmin’s G600 TXi primary flight display with MFD to interface with the existing GNS 430W system and S-TEC 55X autopilot. Not what we call cutting edge gear, but utilitarian enough to get the job done. Flying away from the avionics shop with a $40,000 bill in this airplane isn’t out of the question. You could of course look for one that someone else has spent the money on, and you’d probably have to pay the near $350,000 anyway.

Maybe a 200-knot single is the better choice in this economy, so let’s look for a Mooney TLS. Maybe the insurance company will take a digit off the premium, compared to the twin. We found a 1990 M20M model for $169,000. This speedster has a Lycoming TIO-540-AF1 with 1360 hours since an overhaul in 1998. Best case, that engine should go 2000 hours, but if you found yourself re-engining sooner than that, you might spend close to $60,000, all in.

The avionics are decent, with a Garmin GTN 750 and a good engine monitor, but it still has round gauges, including the maintenance-intensive King KCS55A and KI256 flight director vacuum gyro. When those instruments show signs of needing overhaul—and eventually they will—you’ll be staring down a shop invoice north of $5000. While that’s better than the $20,000 quote for the Garmin display, money is probably better spent on the more reliable and up-to-date electronic system.

Doing the math, this could ultimately be a $250,000 200-knotter, not counting the first annual inspection, which could generate a $10,000 invoice—or more.

These are worst-case scenarios, of course, but we’ve been around the airport fences long enough to know it’s often a reality. It might cost $200,000 to get into the 200- knot club, but you could spend twice as much to stay in it.

—Larry Anglisano

This article originally appeared in the January 2021 issue of Aviation Consumer magazine.

For more great content like this, subscribe to Aviation Consumer!