A Step In The Flight Direction

I recall a chilly morning at the Reno-Stead airport when I realized I no longer felt like a total outsider. It was 2017, the first year I towed Jeff LaVelle’s trailer full…

Getting to fly the airplanes you’ve been buying parts for is an unexpected treat. Even though, in this case, it happened after I’d left Glasair Aviation. Still counts!

I recall a chilly morning at the Reno-Stead airport when I realized I no longer felt like a total outsider. It was 2017, the first year I towed Jeff LaVelle’s trailer full of tools, hardware and a spare Hartzell propeller to the National Championship Air Races in Reno, Nevada. He raced his Glasair III and I stood alongside him as his crew chief. I stared at the runway and realized I’d spent nearly every morning at an airport over the last two years. This wasn’t something I envisioned for myself, given my upbringing. I let the thought unfold into a smile. Soft but bright, like the light pouring over the surrounding hillside.

I’d seen videos of Jeff race, but to watch him in person was otherworldly. The sound of his twin-turbo 580 revealed an even bigger smile and, before I knew it, my cheeks hurt. LaVelle taught me many things these past few years, but watching him fly his homebuilt to first place that year confirmed that my decision to dive headfirst into the world of Experimental aviation was the right one.

Stumbling Into Opportunity

Like many, I didn’t know what I wanted to do after college. In 2015 I deferred my acceptance to graduate school, opting to finally learn what working full-time was all about. I stumbled upon a buyer role at Glasair Aviation and, despite knowing nothing about it, allowed myself to float down a sea of vinyl ester.

I didn’t grow up in a “flying family” or have any knowledge of airplanes, let alone homebuilts, prior to this job. My background also wasn’t in purchasing—it was in communication and public relations. Regardless, I knew I’d found something special and desperately wanted to learn everything I could about these airplanes people were building in their garages.

My desire to grow in this field didn’t come without challenge. I had a lot to learn—the first lesson being slacks were not part of the dress code. I wondered how long it would take me to accumulate a solid collection of airplane T-shirts. To my surprise, there were no work instructions and most of the purchasing processes left the building with the previous buyer. No one person was designated to train me; I was tossed from person to person. Not to mention, the thought of spending someone else’s money terrified me. I started to question my decision to ditch grad school.

I went from relying on straightforward syllabi to guide me through college to reaching for confusing yellowed manuals on a dusty shelf in Harry DeLong’s office. (Harry was one of those do-everything types at Glasair Aviation, a font of knowledge and someone who helped me decode the company.) Thankfully, since I was fresh out of college, I was in the habit of studying. So that’s what I did. I studied the aircraft and picked the brains of my peers. Most people were friendly and happy to help. Even the shop boys who tricked me into calling Sensenich to ask for “prop wash” became valuable resources. There were real jerks too—like the guy who yelled “I want to speak with someone who knows what an aileron is!” at me through the phone, which left me crying in the bathroom.

This was a male-dominated industry and it brought forth flashbacks of trying to keep up with my older brother, who woke up one day and knew how to snowboard and wrench on his Volkswagen. He somehow understood these things, whereas I struggled to grasp them, but really wanted to. I found engines interesting, but knew nothing about them. Nobody pulled me aside as a kid and said, “I’m going to teach you how to change the oil.” It was just assumed I didn’t care to know and I was too afraid to ask.

To know nothing about the inner workings of airplanes and be trusted to buy parts for them was scary and challenging. At this point in my life I lacked self-confidence, and not knowing how to do my job properly didn’t help. Although I wasn’t a gearhead, I had something of my own that came naturally to me, which in my opinion is much harder to teach. I was able to communicate. In hindsight, I know this is what allowed me to stick it out when things got tough.

My phone’s photo library quickly filled with pics of half-welded engine mounts and botched wheel pants. Things that, like myself, needed some work. This job was a fresh start for me. A chance for me to build the life I always wanted, one Harbor Freight run at a time.

Building A New Life

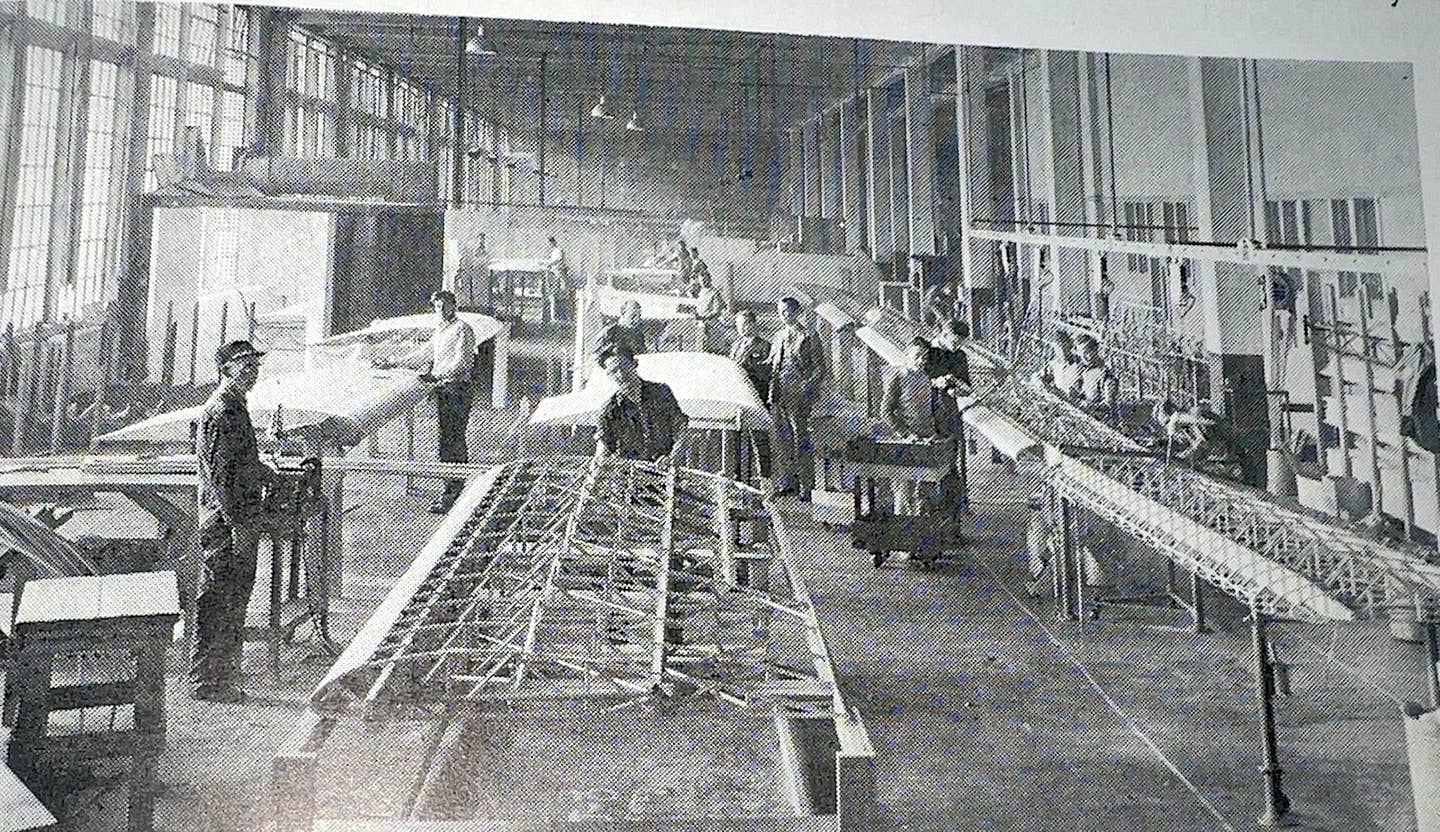

Between the smell of styrene and the banging of rivet guns, there was so much commotion in the factory—and it all excited me. But most of all, the people were what kept me coming back. This position provided me with a family bonded not by blood, but resin. I lost my dad to pancreatic cancer when I was 17 years old and these people helped patch a hole in my heart I’d been longing to fix.

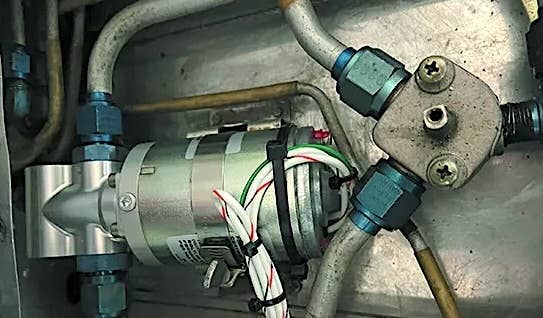

With this furthered education and unexpected healing came confidence. I knew all along this detour was risky, but I was thankful I trusted my gut reaction to go down this road because it started me down a path to becoming the person I always wanted to be. I developed a flow when it came to buying and built relationships with vendors. I bought everything from washers to engines. Oil filters to avionics. Machined parts, carbon cloth, gloves, propellers and everything in between. I learned how to speak airplane and if someone asked me to buy a 1/2-inch bolt I knew to ask if they wanted standard AN, high-strength NAS or one from the hardware store.

I was excited to see CAD drawings cross my desk again. I’d taken numerous drafting classes in high school and missed being a part of that realm. Drafting was one area where I could keep up with my brother and his friends. We made stickers and vinyl decals for T-shirts and when our dad passed, the drafting teacher let my brother and me hide out in his classroom. It was a safe haven for us during our formative years.

When Glasair got a vinyl cutter I volunteered to print the N-numbers and dubbed the machine “Stoddard-Vinylton,” a nod to Glasair’s early days as Stoddard-Hamilton. This industry engaged the mathematical part of my left brain and the creative part of my right. It was all-encompassing, the perfect combination of hard and soft science. It also brought about memories from my youth, as if everything I’d learned prior to this was preparing me for this job.

Slowly but surely I molded my life to revolve around these small composite airplanes. I spent hours in that office day-dreaming about learning to fly, which I eventually did. Ted Setzer took me up for my first flight in his Sportsman and the former CEO of Jeppesen, Mark Van Tine, came to Glasair for a project and gifted me an entire Jeppesen Private Pilot kit and flight bag. My introduction to flight training unfolded more beautifully than I could’ve imagined.

To this day, none of my flight instructors have been familiar with homebuilts. Most are in their 20s and got into flying with hopes of joining the airlines, not spending hours in a hangar hunched over a tail kit. The word “experimental” brings concerned looks, not jealousy or excitement. I was surprised and saddened to witness this. I assumed everybody got their start through kit aircraft and worked their way “up” to certified.

Unexpected Perks

Magically, whether it be walking through the Glasair parking lot, thermos in hand, or weekend mornings preflighting an airplane at a nearby flight school, I reached a point where starting my day among the blue taxi lights became the norm. I held my head a little higher.

Glasair asked me to go to AirVenture, where I got to meet suppliers like Robbie Grove of Grove Aircraft, and found myself talking to them like I’d been a GA person my entire life. I got to walk through grassy parking lots filled with homebuilts and see the hard work these builders put into their planes, reinforcing my hopes of building someday. I took mental notes of what I might want. What was once just another small airplane became a GlaStar. Did it have a large aft baggage door? What about the interior? Zolatone?

Then seven-time National Gold Sport Champion Jeff LaVelle came into my life. He’s somebody who showed me the ultimate potential of a kit aircraft: 400-plus-mph. He recognized my enthusiasm and drive to fully immerse myself in this field and asked me to join him at the races. I think it’s important for young pilots to find friends and mentors who will remind you why you got into flying in the first place: to not only have fun, but challenge yourself. I found it much easier to get out of my comfort zone and earn my private pilot certificate with people like Jeff by my side.

Watching other pilots and aviation enthusiasts excel in the many areas this field has to offer is what kept me in this industry. Although I now procure aluminum for the commercial side of aviation (dare I say the B word?), I will always reflect fondly upon my unique introduction to aerospace.

I want other younger pilots to experience the joys of Experimental aviation. These planes take you places, both literally and figuratively. They’ve taken me upside down in the skies above Arlington, Washington, and to KITPLANES. We younger pilots often get caught up in the “I’ll be happy when I get my next rating” mentality, and I think there’s more to be had in these in-between moments in a hangar with an experienced builder. Take a ride in an RV; the airlines will always be there. And for anyone who’s questioning a recent career move, I’m here to say life has a funny way of working out.

This article originally appeared in KITPLANES. For more great content like this, subscribe to KITPLANES!