The Desanctification of AoA

Because I lack the common decency to avoid saying I told you so, this is an I-told-you-so blog. Well, sort of, because what I thought or maybe predicted would happen didn’t happen. At least not in the way I might have imagined.

Because I lack the common decency to avoid saying I told you so, this is an I-told-you-so blog. Well, sort of, because what I thought or maybe predicted would happen didn’t happen. At least not in the way I might have imagined.

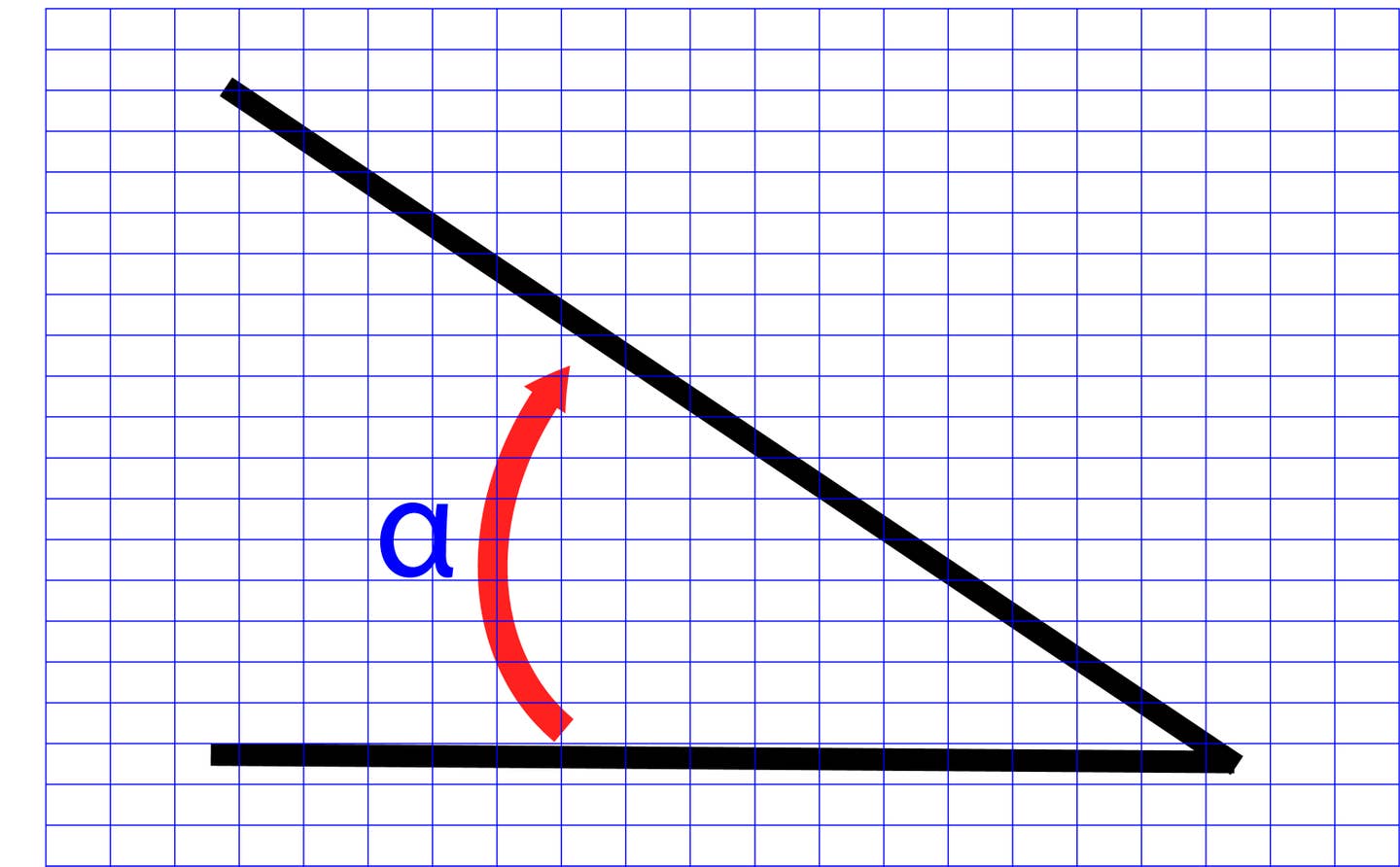

About five years ago, there appeared on the market a handful of angle-of-attack indicator products. I’m not sure why the timing unfolded as it did, but I think it might have been a confluence of several events. One, the technology became cheaper and easier to deliver to market, including displays, envelope protection was becoming a thing, the FAA relaxed the approval process and we were starting to talk about stalls as a persistent accident cause. Wait, what the hell am I saying? When have we not talked about stalls as a persistent accident cause? Wilbur and Orville even had a name for the spin that follows: well drilling.

Thanks in part to marketing fluff, in part to appreciative press reviews and yes, a dose of unfounded expectations, AoA suddenly became the galloping knight that would banish stall accidents or at least reduce them. If the promo didn't say that in so many words, it encouraged the belief. It was just a good thing to have, many seemed to agree. Not me.

At the time—and still—I think the only way AoA indicators will make a dent in GA stall accidents is if the technology is thoroughly integrated into a persistent, industry-wide ab initio training doctrine. And even then, it risks being just another hey-look-at-me light among many that seem to be multiplying on the typical glass panel.

I could never understand why people reasoned that a pilot too clueless to sense impending stall in the usual ways—control feel, aural cues, airspeed, flight attitude—would somehow miraculously have the cognizance to interpret yet another beseeching indicator vying for his task-saturated attention. I wouldn’t be surprised if the very pilots most in need of this technological crutch are the very ones least capable of reacting to it.

Turning my attention to the Boeing 737 MAX—you knew I would—a similar sort of hubris may have been at work. AoA data has been available in airliners for decades and Boeing has as much experience with it as anyone. So much so that it apparently felt confident enough to use a single AoA vane to drive the MCAS autotrim system that was, inexplicably, capable of applying full nose-down stabilizer trim in certain circumstances that proved not that rare. Boeing has since seen the flaw in that approach and has defanged MCAS’s aggressive trim and plumbed what's left of it into both AoA vanes. If the lesson sticks, designers will tap the brakes next time they think single-sensor input is a good enough in a world driven by 10-9 expectations.

As Boeing’s travails were unfolding, Cirrus had its own night in the barrel with the AoA system on the VisionJet. Again, faulty data from the vane could inappropriately trigger the airplane’s stall-protection system. Although not as aggressive as Boeing’s system, Cirrus was worried enough to ground all the VisionJets until the vanes could be replaced or repaired. Cirrus says the airplanes are just getting back into the air now. But they still rely on that single vane, a somewhat delicate slice of metal exposed to the errant elbow of the fueler or curious bystanders.

The Luddites among us will—not without reason, perhaps—decry these developments as yet another example of how automation is displacing the basic understanding of how to fly an airplane. I wouldn’t go quite that far because I think envelope protection is fundamentally a sound idea. The technology is there and it works. Why not apply it and use it?

But then we get a little too clever by half, as the Brits might say. The expectations of what this tech might achieve are overinflated as evidenced by Boeing’s conviction that the pilots didn’t even need to know about it and the GA expectation that sure, an AoA indicator on the panel might tamp this stall thing down. In Boeing's case, the company apparently thought that even though the typical 60th percentile pilot needed a little stabilizer nudge to make the airplane feel right, he or she would nonetheless have no problem at all sorting out a single-side stick shaker with the electric trim running intermittently amok and stick forces escalating to the Charles Atlas range.

I have no objection to AoA in light aircraft, but I have no great expectations for its impact, either. In flying these systems from time to time, I have found just one killer app for AoA: Flying max-performance short-field approaches and landings. You can just notch the airplane right into the perfect angle and ignore gyrations in airspeed. When you get the knack of it, the performance uptick is quite impressive. If I were going to install one, that would be the reason.

Otherwise, on some days and maybe even for good, I would like to declare a moratorium on industry hand wringing over stall accidents and further things we might do to prevent them. If you can levitate the damn airplane off the runway, you can surely figure out stalls and how to avoid them without a 10-hour block of classroom instruction. Go out in the airplane and do it. You don’t need an instructor. Just go fly the stall series and see what it looks, sounds and feels like. Fly departure stalls and turning stalls and accellerated stalls. If that proves boring, you’re probably stall proof. You could stick an AoA on the airplane just for the entertainment value.